![]()

TWO | Post-colonial: Africa and Asia

3 | Mapping everyday practices as rights of resistance: indigenous peoples in Central Africa

CHRISTOPHER KIDD AND JUSTIN KENRICK

Introduction

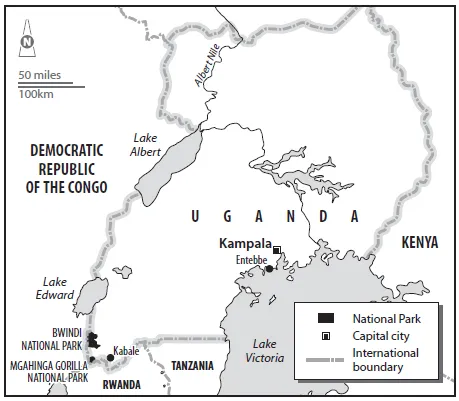

This chapter will focus on Central Africa by specifically highlighting the experiences of the former hunting and gathering Batwa people of south-west Uganda. Historically, the Batwa were forest-dwelling hunter-gatherer people living within the high-altitude forests in the Great Lakes region of Africa. The Batwa are widely regarded by their neighbours and historians as the first inhabitants of the region, who were later joined by incoming farmers and pastoralists approximately one thousand years ago. Today, the Batwa are still living in Rwanda, Burundi, Uganda and eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. In each of these countries the Batwa exist as a minority ethnic group living among the largely Bahutu and Batutsi populations. Slightly more than 6,700 Batwa live within the present state boundaries of Uganda, with approximately half living in the south-west region of Uganda. The Batwa in this region are the former inhabitants of Bwindi, Mgahinga and Echuya forests, which comprise the final forested remnants of their ancestral territories. Recently, however, they have suffered evictions and exclusions from these forests, primarily as a consequence of the creation of protected areas. As a result of this exclusion from their ancestral forests, the majority of Batwa suffer severe isolation, discrimination and socio-political exclusion. The Batwa’s customary rights to land have not been recognized in Uganda and they have received little or no compensation for their losses, resulting in a situation whereby almost half of Batwa remain landless and virtually all live in absolute poverty. Almost half of the Batwa continue to squat on others’ land while working for their non-Batwa masters in bonded labour agreements. Those who live on land that has been donated by charities still continue to suffer poorer levels of healthcare, education and employment than their ethnic neighbours.

In order to map out ‘indigeneity’ in this context we will have to map out responses from not just indigenous peoples but also from the non-indigenous partners in the indigenous experience. We begin this chapter by detailing and providing analysis of two interviews carried out with indigenous rights activists in Uganda. In Part Two we move on to an analysis of state responses to indigeneity in sub-Saharan Africa and offer some explanations for why indigeneity may be so hard to accept in the African context. Finally, in Part Three of this chapter, we provide a fresh and optimistic way to understand indigenous peoples’ use of indigenous identity by drawing on examples from Australia and Central Africa to show that rather than inciting confrontation (as many African governments fear), indigeneity can actually be a tool of accommodation that seeks to build bridges instead of deepening divisions.

3.1 Batwa ancestral territories: map of Uganda showing the remaining forests in south-west Uganda that were once the Batwa’s ancestral homes. Upon their eviction from these protected areas, and without any resettlement programme from the government, the Batwa were left landless on the edges of these protected areas where many of them continue to stay.

1 INDIGENEITY AS LIVED EXPERIENCE

Interview 1

The interview is between Chris Kidd and Fred, the chairperson of a Batwa-run organization that seeks to advocate on behalf of its fellow Batwa. Despite coming from a remote community near the border with Rwanda, Fred has travelled to Europe and West Africa in the two years he has been chairperson to attend conferences and workshops. Fred’s responses are in Rukiga, his native language, and translation into English is provided by a member of Fred’s organization.

In the Batwa’s language Urufumbira, the concept of indigenous is translated as abasangwa (the people found) butaka (on the land). (For a discussion of umusangwa butaka among the Batwa in Rwanda, see Adamczyk 2011.)

CHRIS: What do you understand abasangwa butaka [indigenous] to mean?

FRED: I feel that IP is the first occupant of that land where they are found.

C: Who are those people in Uganda?

F: Those people in Uganda are the Batwa.

C: If the Batwa are indigenous, apart from being first on the land, are there any other attributes that are special to the Batwa as indigenous people?

F: [Not clear about the question] Yes, we have Gatwa, Gatutsi and Gahutu.

[While Muhutu refers to a single Hutu person and Bahutu refers to the Hutu people, Gahutu is the name of the progenitor of the Hutu people. In creation stories the Batwa, Bahutu and Batutsi progenitors are represented by Gatwa, Gahutu and Gatutsi.]

C: What makes the Batwa different from these other Gahutu and Gatutsi? Is the only difference that they were the first to be there?

F: The only difference from Gatwa, Gahutu and Gatutsi is that Gatwa stayed in the forest whereas Gatutsi when he came he was a person with the cattle, and when Gahutu came also following the Gatutsi he was a peasant. So Gatwa never did all that. Gatwa stayed in the forest. He did not think of doing what Gatutsi and Gahutu were doing.

[‘Peasant’ is used by the translator to refer to a farmer in this instance. The Batutsi are stereotypically cattle keepers, the Bahutu farmers, and the Batwa hunter-gatherers.]

C: Do the Gahutu and the Gatutsi accept that the Batwa were the first on the land?

F: Yes. If that Gatutsi and Gahutu can follow, what was there? The Gatwa was the first occupant. Yes, if Gahutu and Gatutsi knew they found us on the land there is no reason why they can’t believe that Gatwa was the first occupant.

C: Is it true that in the stories of creation that the Bahutu and Batutsi have, most of those stories suggest that the Bahutu, Batutsi and Batwa were all created together at the same time?

F: Gatwa, Gatutsi and Gahutu originated from one man but Gatwa was the leader. Gatwa stayed all the time in the forest. When Gatutsi and Gahutu joined hands for them they had to prosper and they achieved a lot. As a result they took over the leadership of the Gatwa. Gatwa was actually the original person to be leading while in the forest.

[The insinuation here is that while all the brothers stayed in the forest their relationship remained equal but that at some point Gahutu and Gatutsi left the forest and ‘joined hands’. This positions the forest as a realm of egalitarian relations and the non-forest world as a realm of discrimination. It also provides an astute explanation of the present predicament of the three peoples; while Gahutu and Gatutsi joined hands to arrive at their current ‘developed position’ in society, they left the Batwa behind in the ‘undeveloped’ margins of society.]

C: If the Batwa were the first on the land, why has the government not respected their land rights if they were the first on the land?

F: ’Cause of ignorance. Batwa are ignorant.

[In this and other sections of the interview, Fred uses language which suggests that he is blaming the Batwa for their current situation through describing them as lazy or ignorant. His attitudes can be seen to mirror those very same attitudes which are levelled at the Batwa by external groups who blame the Batwa and what is seen to be Batwa culture for their perceived backwardness. On some levels this may indeed be true given the Batwa receive a range of narratives that are imposed on them and that urge them to become educated, developed, sedentary, agricultural and Christian. These narratives are imposed on the Batwa by the government, aid agencies, development organizations, missionaries and their local neighbours, so it is no surprise that given such a tirade of narratives the Batwa often adopt these narratives as their own.

However, this is not just a case of impoverished and passive Batwa participants, and the comments from Fred can also be read as an empowered call to arms to his fellow Batwa. These imposed narratives which blame the Batwa for being ignorant may be understood as being about the imposing groups not taking responsibility for the impact they are having on the Batwa, enabling them to ignore the role that the structural forces, from which they benefit, play in disempowering the Batwa. However, for Fred, blaming the Batwa is about taking responsibility, about getting Batwa to see their responsibility for re-creating the situation and for finding a way out of it. In such a situation the most empowering step may be to take responsibility. In the tone of his comments, Fred is showing his frustration at the Batwa’s failure to take full advantage of the few opportunities that are offered to them, and he is demanding that the Batwa stop replicating the situation they have been placed in.]

C: What are the Batwa ignorant of?

F: They are not educated, they do not mind to follow up their rights, not knowing themselves, not understanding themselves.

C: Does the government then take advantage of the Batwa?

F: Yes.

C: Given that you are the chairman of the Batwa organization, what is your vision for the future of the Batwa people?

F: What I see is that since they have well-wishers, donors and friends, in the future Batwa will be different people like Bahutu.

[The demand by Fred for his people to be ‘like Bahutu’ may have more than one interpretation. On one level this can be read in a similar light to Batwa describing themselves and their communities as ignorant and backward. Given the narratives that are imposed on them – which range from them being described as ignorant and undeveloped by the state to savage and dirty by their ethnic neighbours – it is no wonder that many seek to claim that they are not like other Batwa and more like those who discriminate against them (see Adamczyk 2011; Leonhardt 2006; Namara 2007: 22–3).

On the other hand, when Fred envisions a future for the Batwa in which they are more like the Bahutu, he is also making a statement that refers to the current inequality between the two groups, and he is hoping that one day the Batwa will be regarded as equal to their neighbours – whether by their neighbours, the government or other external groups that currently discriminate against the Batwa.

In many ways the first context suggests a process of assimilation whereby the explicit and implicit characteristics of the Batwa are replaced by the characteristics of the dominant ethnic groups. In this scenario the Batwa have no ability to let any particular characteristics remain as all are replaced. The second scenario, however, suggests a much more equitable process of integration, whereby the Batwa are not demanding the retention of their perceived cultural characteristics but instead are demanding control of how their culture changes and adapts in present and future contexts.]

C: When you say you want the Batwa to be like Bahutu, what do you mean?

F: After eviction, Batwa were really unhappy and were not listening to anyone. Today they can now listen to what a good person is advising them to do. So that listening is also a step forward, that there are good things in the future, like when you tell a Mutwa to do this today he or she does it, like agriculture, they go and do agriculture. In that listening and doing the agriculture there is a chance of getting food whereby you can no longer now depend on someone or beg instead, by having listened you are now doing things on your own. Secondly, if there is any injustice, a Mutwa now because of listening knows where to go for that injustice done to him. If you keep on listening like that and there are more good people coming to help them like there is now, in the future they could even have surplus food for them whereby even the Hutu can buy from them. Then they will have equality in that manner.

C: If we look forward to that day when the Batwa have the same opportunities as the Hutu, will there still be things which are particular to the Batwa and not the same as the Hutu? When they both have the same opportunities will there still be some things which are special to the Batwa which are not available to the Hutu? If the Batwa are to have the same opportunities as the Hutu to live the same lives will the Batwa still be interested in the forest?

F: If there is opportunity that equality prevails, you get everything that like the other group are getting, then I don’t see why the people would want to go to the forest.

C: But there are still some members of Batwa Organization who want to go to the forest and get the things from there, to visit their ancestors.

F: Yes, true. Among ourselves there are those who want to visit the forest, yes, it is true, because we need to practise our culture and visit the ancestral lands, but we feel we should visit and come back and we don’t stay actually inside there. One thing is that if we have those activities we were talking of, equality outside the forest, we will be having land, animals, goats in particular and food, then what remains is for us to go there and do our cultural practices that we don’t lose them. But we don’t look at what’s there and look to grab it.

[This apparent contradiction between not wanting to go to the forest and needing to practise their culture in the forest is most probably a mistranslation or a misinterpretation by the translator of the intent of the question. When the term ‘go to the forest’ is used this implies going to live in the forest, in contrast to visiting the forest to maintain cultural practices. Most Batwa do not want to reside (‘go’) in the forest but do want to visit the forest to maintain their relationship with it.]

C: In this future that you see for the Batwa, where you see equality, do you see the forest as always being important to the Batwa?

F: Yes, Batwa can still be attached to the forest because of their culture but the forest is not only good for the Batwa. It is good for everyone because within the forest is where we get air, is where we get the rains, and some food also, so people should learn how to take care of the forest and not particularly for the Batwa but for the good of everyone.

[This response may be influenced by his recent trip to the Convention on Biological Diversity – Convention of Parties (CBD-COP) in Bonn, Germany, as well as the Batwa’s inclusionary attitudes towards the ownership and management of their ancestral forests – see later sections of this chapter.]

C: This vision for the future. What steps d...