eBook - ePub

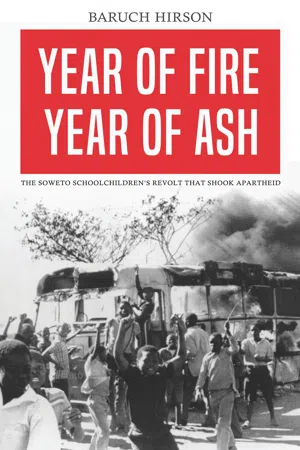

Year of Fire, Year of Ash

The Soweto Schoolchildren’s Revolt that Shook Apartheid

- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

'We can say without fear of being contradicted by history, that June 16, 1976 heralded the beginning of the end of the centuries-old white rule in this country.'

Nelson Mandela

Originally banned on publication by the apartheid government, Year of Fire, Year of Ash is an eye-opening account of how, in June 1976, 20,000 school students faced down the tanks and guns of a vicious racist regime, in a revolt that galvanized the black working-class and became a pivotal turning point for the anti-apartheid movement. More than this, the book overturns much of the conventional logic that served to explain the event at the time, showing it was not simply a student protest, but part of a wider uprising.

Released in this new edition to mark the fortieth anniversary, Year of Fire, Year of Ash provides an unparalleled insight into the origins and events of the uprising, from its antecedents in the 1920s to its role in inspiring global solidarity against apartheid. As South Africa experiences a new wave of popular discontent, and as new forms of black consciousness come to the fore in movements around the world, Baruch Hirson's book provides a timely reminder of the Soweto revolt's continued significance to struggles against oppression today.

Nelson Mandela

Originally banned on publication by the apartheid government, Year of Fire, Year of Ash is an eye-opening account of how, in June 1976, 20,000 school students faced down the tanks and guns of a vicious racist regime, in a revolt that galvanized the black working-class and became a pivotal turning point for the anti-apartheid movement. More than this, the book overturns much of the conventional logic that served to explain the event at the time, showing it was not simply a student protest, but part of a wider uprising.

Released in this new edition to mark the fortieth anniversary, Year of Fire, Year of Ash provides an unparalleled insight into the origins and events of the uprising, from its antecedents in the 1920s to its role in inspiring global solidarity against apartheid. As South Africa experiences a new wave of popular discontent, and as new forms of black consciousness come to the fore in movements around the world, Baruch Hirson's book provides a timely reminder of the Soweto revolt's continued significance to struggles against oppression today.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Year of Fire, Year of Ash by Baruch Hirson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Cultural & Social Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

From School Strikes to Black Consciousness

1. The Black Schools: 1799-1954

Schools: Segregated and Unequal

In 1971, every white school child in the Transvaal was given an illustrated volume to ‘commemorate the tenth anniversary of the Republic of South Africa’. On the subject of education the authors of the book declared:

The cultural and spiritual developmental level of a nation can with a fair amount of certainty be ascertained from the measure of importance the nation concerned attaches to the education of its children …

Only by developing the mental and spiritual resources of the nation to their maximum potential, can the need of the modern state for fully trained leaders, capable executives, industrialists with vision, dedicated teachers, scientists, engineers and skilled personnel be properly supplied.1

The subject of education was then explored in terms of facilities provided, buildings and equipment used:

Not only has the equipment to be suitable with a view to efficient teaching, but the physical well being of the pupils must be taken into consideration.2

This was a state publication designed to instil patriotic fervour in the breast of every white child. It was the white child’s well being that was being discussed, and the white child’s future as leader, executive, industrialist or professional that was being described. It was also a self-congratulatory book; and the administration was satisfied with the role it played in providing facilities for the schools. Accompanied by lavish illustrations there were eulogistic descriptions of library facilities, school equipment and sports grounds, and also of teacher training, of psychological and guidance services, and of educational tours.

The claims made in this commemorative volume do not stand serious scrutiny. The educational system (for Whites) had serious defects which had been debated openly for many decades. The standards in many of the schools were low, the social sciences were designed to show the superiority of the Whites, and the natural science courses were antiquated in content. With all their blemishes, the white schools were however lavishly equipped, and the cost of educating each pupil was high.

If the commemorative volume had set out to describe the conditions of all sections of the population, a very different publication would have been necessary. In the realm of education alone, it would have had to be shown that the conditions of the vast majority of the youth were very different from those of the Whites. The Transvaal Province was responsible for financing and directing the education of all Whites below University level. And being the area of greatest population density, the Province catered for 52 per cent of the white youth of the country: that is, some 400,000.

The responsibility for African education, on the other hand, had been placed in the hands of the central Department of Bantu Administration and Education since 1954. Unlike the Whites, for whom education was compulsory, African youth had great difficulty in obtaining education, and what they were given was grossly inferior. Whereas every white child would complete primary school, and one quarter would complete the secondary school in 1969 (the date at about which the commemorative volume was being written),3 70 per cent of all African children who found a place in the schools would leave after four or less years of attendance. Less than four per cent would enter secondary school, and few of these would complete the five year course.

Some comparative statistics indicate the disparities in the schooling of Whites and Africans. In 1969 there were 810,490 white youth at school, and the total cost of their education was R241,600,000 (or £120.8 million). In the same year 2,400,000 African children were at school. The cost of their schooling, together with the cost of the infinitely more expensive University education, was R46,000,000 (£23 million).4 In the Transvaal that year, when white primary and secondary education cost R88,000,000, the estimated cost per student for the year at school was: primary level — R175; secondary level — R234; vocational and agricultural high school — R350; and teacher training — R589.5 The Minister of Bantu Education stated that the expenditure on each African child in 1969 was: primary level — R13.55; secondary level — R55.6 African youth were not presented with the commemorative volume in 1971.

Since the mid-fifties African education has been directed by the Department of Bantu Affairs and Development (a department which changed its name, but not its function over the years). This has, however, not always been the case.

First Steps in the Cape

African education was not really required before the turn of the nineteenth century. The African people were still unconquered, and were not yet incorporated into the Cape economy and the schools were open to the children of freed slaves, or children of colour who had the opportunity of attending.

The first school built specifically for African children was established, in 1799, near the present site of Kingwilliamstown, by Dr. J.T. van der Kemp of the London Missionary Society. It was 21 years before other missionary bodies followed suit, and established schools for Africans in the Eastern Cape. Some missionaries moved further afield and built schools in the uncolonised interior, moving into Bechuanaland, Basutoland and the Transvaal.

The need for further educational facilities was apparently first felt after the freeing of the slaves in 1834. To cope with the children who were turned free with their parents more schools were required because of ‘the need to extend social discipline over the new members of a free society’.7 Through the nineteenth century and during the first quarter of the twentieth century African schooling was provided almost exclusively by the missionary societies. The missions were given land, but they provided the buildings, the teachers and most of the funds. Only a small portion of the expenses incurred, and usually only the salaries of staff, was provided by government grants (or after 1910, by Provincial Councils).

The first government grants to mission schools, of from £15 to £30 per year, were only provided after 1841, and were exclusively appropriated for the ‘support of the teacher or teachers’.8 It was only after that date that the number of schools increased considerably.

In one respect the colonial governments were bountiful. Land was available for the taking after the expulsion of the Africans, and mission stations were given extensive lands by the Governors on which to establish their schools, hospitals, colleges, as well as farms and orchards. The Glasgow Missionary Society, for example, received a grant of some 1,400 acres just inland from East London, and on this they eventually built the Lovedale school complex. The schools also needed state patronage and assistance which was to come with the appointment of Sir George Grey as Governor of the Cape from 1854 to 1861. Grey’s task, as he conceived it, was to integrate the African peoples into the economy of the Cape, and he sought a solution by means of which:

The Natives are to become useful servants, consumers of our goods, contributors to our revenue, in short, a source of strength and wealth to this Colony, such as Providence designed them to be.9

To assist Providence’s design, Grey meant to break the power of the chiefs and educate a new class of Africans.

Grey brought with him the ideas on education then prevalent in Great Britain. Although he wanted an educated minority, he maintained that Cape schooling was too bookish, and proposed that the missionaries pay more attention to manual education. What was said by a Justice of the Peace in Britain in 1807 seemed apposite to the administration in the Cape in the 1850’s:

It is doubtless desirable that the poor should be generally instructed in reading, if it were only for the best of purposes — that they may read the Scriptures. As to writing and arithmetic, it may be apprehended that such a degree of knowledge would produce in them a disrelish for the laborious occupations of life.10

Grey believed that the missionaries could provide the education he envisaged for the Blacks. He consequently met members of the Glasgow Missionary Society (later a branch of the Free Church of Scotland) who had already established an elementary school at Lovedale near Alice in the Eastern Cape.11 As a result of these discussions the course of Cape educational policy for the nineteenth century was laid down: elementary instruction in literacy plus manual instruction for the majority of pupils, and a higher level of education for a small elite.

Lovedale opened an industrial department and tuition was also designed to:

give higher education to a portion of the native youths, to raise up among them what might be called an educated class, from which might be selected teachers of the young, catechists, evangelists and ultimately even fully-qualified preachers of the gospel.12

Grey also persuaded the Rev. John Ayliff to start an industrial school at Healdtown, near Lovedale, and undertook to support and subsidize missionary institutions that provided such training.13 Henceforth the missionaries were to provide nearly all African education, but the government exercised overall control by virtue of its grant of funds. The government aimed in its policy at a disciplined population that would become an industrious workforce.

By 1865 there were 2,827 African pupils enrolled in the mission schools and by 1885 the number had increased to 15,568. Most of the schools however:

being short of funds, ill-equipped, with inadequately trained and paid teachers and children often under-fed, over-tired and staying too short a time to benefit — gave the mere smattering of elementary letters and touched only a fraction of the child population.14

Reports by successive Superintendents-General of Education in the Cape, on the standard of education in most of the schools, were scathing. In 1862 Dr. Langham Dale found that only five per cent of pupils in these schools could read, and few of the teachers had passed Standard 4. Dr. Dale’s successor, Sir Thomas Muir found that 60 per cent of all African children at school did not reach Standard 1. In 1882, Donald Ross, the Inspector-General, said that half of the 420 schools in Kaffraria (Eastern Frontier area), Basutoland and the Cape could be closed without loss to education.15

Lovedale, Healdtown, St. Matthews (at Keiskama in the Ciskei) and a few other schools were exceptions in being able to produce trained craftsmen and youth who completed Standards 3,4, and even 5. Many of the other institutions were little more than disciplinary centres where youth were kept occupied. Dr. Dale explained educational policy as follows:

the schools are hostages for peace, and if for that reason only £12,000 a year is given to schools in the Transkei, Tembuland and Griqualand, the amount is well spent; but that is not the only reason — to lift the Aborigines gradually, as circumstances permit, to the platform of civilised and industrial life is the great object o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- About the Author

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Tables and Maps

- Foreword by Shula Marks

- Abbreviations

- Nineteen Seventy-Six by Oupa Thando Mthimkulu

- Introduction

- Part 1: From School Strikes to Black Consciousness

- Part 2: Workers and Students on the Road to Revolt

- Part 3: Black Consciousness and the Struggle in S. Africa

- A South African Glossary

- When Did It Happen? A Chronology of Events

- Bibliography

- Acknowledgements

- Index