![]()

ONE

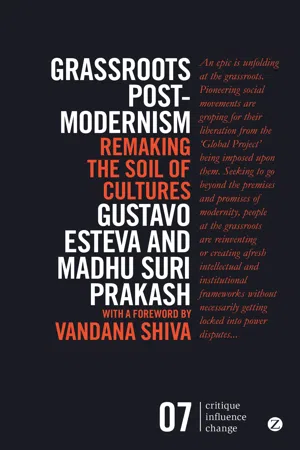

GRASSROOTS POST-MODERNISM: BEYOND THE INDIVIDUAL SELF, HUMAN RIGHTS AND DEVELOPMENT

An epic is unfolding at the grassroots. Pioneering social movements are groping for their liberation from the “Global Project”1 being imposed upon them. Seeking to go beyond the premises and promises of modernity, people at the grassroots are reinventing or creating afresh intellectual and institutional frameworks without necessarily getting locked into power disputes. Ordinary men and women are learning from each other how to challenge the very nature and foundations of modern power, both its intellectual underpinnings and its apparatuses. Explicitly liberating themselves from the dominant ideologies, fully immersed in their local struggles, these movements and initiatives reveal the diverse content and scope of grassroots endeavours, resisting or escaping the clutches of the “Global Project.”

This book is an attempt at sketching the first rough outlines of the unfolding post-modern epic at the grassroots.

GRASSROOTS POST-MODERNISM: AN OXYMORON?

The fallen Soviet giant lies broken, scattered. The Berlin Wall no longer divides the capitalists from the socialists. The champions of the “Global Project” seize the opportunity provided by the end of the Cold War to announce the creation of One World. Five billion present, and the 10 billion waiting around the corner of the new century can all live together in the “global village.” Finally, every individual (man, woman and child) can begin to claim human rights – the moral discovery of the modern era.

The modern era, however, is also ending. From their think tanks and ivory towers, deconstructing the castle of modern certainties, post-modern thinkers are slaying the modern dragons: science and technology; objectivity and rationality; global subjugation by the One Culture – the “culture of progress” spread across the world through the white man’s weapons of domination and subjugation.

While classified under the single banner of “post-modernism,” slayers of the modern hydra emerge from ideologically incommensurable academic camps of the modern academy. Feminist post-modernists speak in a voice alien to the ears of post-modern pragmatists. American post-modernists underscore their departures from European post-modernism. Post-modern poetry does not draw its inspiration from post-modern architecture. Post-modern professional philosophers do not attend the same conferences as the theorists of post-modern art.

Yet, located within the same modern academy, these different ideological camps share an often unspoken consensus – not only of dissent, but also of assent. Regarding the latter, there are some “sacred cows” of the modern era that continue to be revered; cows that are neither touched nor deconstructed; modern “certainties” that retain their hold within the academy, even as all else that is solid begins to melt into thin air. These certainties constitute the remaining unfallen pillars for the world’s “social minorities,” the “One-third World,” now living in fear that their familiar reality of jobs, markets and welfare threatens to collapse around them.

They do not share this reality with the “Two-thirds World.” For the “social majorities” still alive or waiting to be born on this planet, all these familiar elements of the “social minorities”’2 modern world remain alien to their daily lives. Equally alien is the word “post-modern,” coined in the academies of the “social minorities.” It remains totally outside their vocabularies. Both the word and the intellectual fashions that have launched post-modernism might as well be occurring on another planet.

At the same time, the promise and the search for a new era beyond modernity are a matter of life and death, of sheer survival, for these struggling billions – whom social planners call “the masses,” “the people” or “common” men and women. Daily, they are compelled to invent post-modern social realities to escape the “scientific” or even the “lay” clutches of modernity. Modernization has always been for them, and will continue to be, a gulag that means certain destruction for their cultures.

The language as well as the conceptual framework of academic post-modernism are clearly of no use to the “social majorities” for escaping the modern holocaust looming over their lives. It is as ill equipped as that of modernism to describe the experiences of these “down under” billions, struggling to survive the horrors, destruction and threats that the “social minorities” present to their selves and soils, their communities and cultures.

For many years, observing or participating in some of these grassroots struggles, we were unable to speak about them. Caught and severely constrained within the traps created by modern words and concepts, we suffered an incredible impotence, a peculiar inability to articulate what we were seeing and experiencing with people at the grassroots. The modern categories in which we were “educated” would not permit us to understand and celebrate today’s grassroots post-modern pioneers. Rather than a solution to this predicament, academic post-modernism imposed additional inhibiting barriers for us. For their part, while trapped within neither the modern language net nor the “reality” of “educated” modern persons, the “social majorities” creating that post-modern epic seem to share our difficulties in articulating their experiences of modernity.

The birth of this book is an attempt to overcome that predicament.

“Grassroots post-modernism” appears at first glance like a contradiction in terms; an impossible marriage of the academic and the illiterate; a fancy academic concoction to give a new lease to life, however ephemeral, to the fast fading fashion of academic post-modernism, its swan song turned rancorous after tedious intellectual battles.

Yet, we dare to stand by our peculiar juxtaposition of “grassroots” and “post-modernism.” For all its oddities in bringing together two incommensurable worlds, we find it useful for presenting radical insights, which include exploding the meaning of the two elements of the expression.

Through the marriage of “grassroots post-modernism,” we are not trying to give birth to another school of post-modern thought. Instead, bringing these terms out of the confines of the academy to far removed and totally different social and political spaces, we hope to identify and give a name to a wide collection of culturally diverse initiatives and struggles of the so-called illiterate and uneducated non-modern “masses,” pioneering radical post-modern paths out of the morass of modern life.

The epic to which we are alluding does not include all grassroots movements or initiatives. The Shining Path, the American or German Nazis or Neo-Nazis, the Ku Klux Klan, the Anandamargis and others of the same ilk are in our view fully immersed in modernity or pre-modernity. “Grassroots” is an ambiguous word, which we still dare to use because its political connotation identifies it with initiatives and movements coming from “the people”: ordinary men and women, who autonomously organize themselves to cope with their predicaments. We want to write about “common” people without reducing them to “the masses.”

PEOPLES BEYOND MODERNITY: SAGAS OF RESISTANCE AND LIBERATION

Dramatically exacerbating five centuries of modernization during the past four “Development Decades” (Sachs, 1992), the “social minorities” are consuming3 the natural and cultural spaces of the world’s “social majorities” – with the stated intentions of developing them for “progress,” economic growth and humanization.

For their part, with sheer guts and a creativity born out of their desperation, the “social majorities” continue resisting the inroads of that modern world into their lives, in their efforts to save their families and communities, their villages, ghettoes and barrios, from the next fleet of bulldozers sent to make them orderly or clean. Daily, the blueprints of modernization, conceived by conventional or alternative planners for their betterment, leave “the people” less and less human. Forced out of their centuries-old traditional communal spaces into the modern world, they suffer every imaginable indignity and dehumanization by the minorities who inhabit it. The only hope of a human existence, of survival and flourishing for the “social majorities,” therefore, lies in the creation and regeneration of post-modern spaces.

So-called “neoliberal” policies, the free trade catechisms, the proliferation of “transnational” investments and communication networks, and all the other elements that are used to describe the new era of “globalization,” are pushing the “social majorities” even further into the wastelands of the modern world. Relegated to its margins, they are “human surpluses”: making too many babies – an “overpopulation”; increasingly disposable and redundant for the dominant actors on the “global” scene. They cannot be “competitive” in the world of the “social minorities,” where “competitiveness” is the key to survival and domination. The dismantlement of the welfare state designed and conceived to protect the “benefits,” dignity, income and personal security of the world’s “social minorities” means little to the “social majorities.” As “marginals,” they have never had any real access to the “benefits” enjoyed by the non-marginals, the ones occupying the centers of the modern world. While some “marginals” are still striving to join the ranks of those minorities struggling to retain their jobs, their social security or their education, many more are not entering the trap of modern expectations: to count upon the market or the state.

Allotted the ghettoes, the dregs, the toxins, the reservations or the other wastelands of modern societies, the collapse of the market or the state is creating, in fact, new opportunities for them to stand on their own feet; to stop waiting for handouts or the fulfilment of all the false promises of equality, justice and democracy. Reaffirming themselves in their own spaces, they are daily creating the social frontiers of post-modernity; finding and making new paths with wit and ingenuity. The inevitable breakdown of modernity that terrorizes modern minorities is being transformed by the non-modern majorities into opportunities for regenerating their own traditions, their cultures, their unique indigenous and other non-modern arts of living and dying.

This book is an attempt to tell some of their post-modern stories. In this telling, we seek to learn from them their communal ingenuity and cultural arts for escaping or going beyond the monoculturalism of the modern world. In exploring their brands of post-modernism, we explicitly resist the urge of all modern experts: “helping” or “educating” the masses to join the mainstream minority march, headed onward and forward, towards global progress and development.4

Instead, we are inspired to join them in weaving the fabric of their evolving epic – all too human and yet so grand, revealing courage as much as it does the follies and foibles of those “down below” to be themselves; to retain and regenerate their cultures, despite the odds that threaten their lives and spaces.

Following them and their stories, we are drawing upon our own cultural roots and upon our own experiences with ordinary people’s initiatives in Mexico and India. In telling their stories, we seek to offer images that spark the hope and imagination of others. In writing this book, we hope to engage in dialogues with modern men and women, inside or outside the academic post-modern fashion, who find themselves increasingly discouraged or pessimistic with the modern prospect; those who find the prison of the modern self to be an unbearable restriction. We hope to discover among them the allies inside the modern world which grassroots post-modernists badly need for realizing their endeavors more successfully.

Our book is addressed to all those struggling for a multiplicity of voices and cultures currently threatened by the monoculture of modernity, with its monolithic institutions: the nation-state, multinational corporations as well as national or international institutions. With intellectuals and grassroots activists who share our perplexities and predicaments, we are learning to identify and challenge the pillars and certainties that hold up these oppressive monoliths. These intellectuals and grassroots activists are the living links, our flexible swinging rope bridges with the “social majorities.” Our book shares and expresses their hopes for intercultural dialogues, creating new pluralistic discourses: modes of conversation that can appropriately express the conditio humana in a pluriverse. For scholars and activists engaged in understanding and supporting indigenous knowledge systems, our book tries to open doors to escape the study of the world’s “social majorities” as primitive or “underdeveloped” anthropological curiosities. Abandoning projects to help or develop peoples at the grassroots, we invite others to join us in learning from them the knowledge and skills required to survive and flourish beyond modernity.

DAVID AND GOLIATH

According to the myth of modern power, global forces can only be resisted and overcome by counterforces that must also be designed on the global scale. Succumbing to that myth of modern power, our outline of a grassroots epic should have discovered the super-grassroots movement that is a match for the global forces from which the oppressed seek their liberation.

The stories included in our book, however, are not about Promethean heroes; giants who “Think Big.” Instead, they draw upon the experiences of common men and women in villages and barrios. Furthermore, through the entire course of this book we keep returning to stories of the Zapatista movement, which we continue to know and learn from “up close.” This movement “made the news” on January 1, 1994, initiated by a small group of oppressed Indians, living in the poorest province of Mexico – a country that, according to the story told by the Harvard-educated economist, former President Salinas, and candidly believed by all the financial centers of power, stood then on the brink of joining the First World. Both Salinas and some of the billions of dollars he attracted rapidly flew outside the country, once its real condition took revenge over that fantasy world, even as Mexico collapsed into the shambles of monetary devaluation and economic recession.

What relevance can these grassroots stories have for others across the world, interested in their liberation from global forces? What can others learn from a provincial movement of desperately impoverished and oppressed Third World peasants struggling for their cultures, shamed and silenced for five centuries? Is it possible that such a small movement, militarily insignificant, can be of help to other oppressed peoples? Its relevance to other Indian movements or marginals in the Third World needs, perhaps, no explanation. However, how are we to explain the fact that people in more than a hundred countries reacted to the Zapatistas’ liberation initiatives with meetings, encounters, mobilizations and thousands of specific proposals? How do we explain the fact that two Italian villages declared themselves Zapatistas, while stating that the questions and ventures of the latter are also their own? How are we to explain the independent initiatives that started disseminating daily news and comments about the Zapatistas through three electronic networks only a few weeks after January 1, 1994? Or that, a few months later, were publishing books in at least five languages and ten countries? How are we to explain the reaction in five continents to their invitation to animate the “international” of hope, overcoming the oppression of global neoliberalism?

By studying the impact of this movement, we cannot but recognize that it is not just a “case,” a curiosity or a “model” for sociologists, anthropologists, political philosophers or critical cul...