![]()

Part I

Introduction

![]()

Chapter 1

What is aquaculture?

Do you enjoy fishing? Do you enjoy seafood? Do you like the idea of your children and your children’s children being able to enjoy the same? If so, read on. This book is about aquaculture. It is about what aquaculture can and does provide the human race. It is about what aquaculture does well and where mistakes have been made. It is about informing the public mindset and, with new understanding, embracing aquaculture as a critical element of the future we would like to share with one another. It is, I hope, about understanding aquaculture, fully and appreciatively. First, we must understand aquaculture in the simplest terms – its definition and basic forms.

Aquaculture takes its name in the manner of agriculture, replacing ager (Latin for field) with aqua (water) and combining it with cultura (growing, cultivation) to efficiently describe a multitude of practices (Oxford University Press, 2016). A number of related terms have been invented to try to define the rearing of plants or animals in either fresh or saltwater more narrowly. However, the inherent definition of aquaculture – literally “water cultivation” – applies to all of these endeavors and describes them with a simple elegance the other terms lack. There is a reason the title of this book is Understanding Aquaculture and not, for instance, Understanding Mariculture, Hydroponics, Ocean Ranching, and Fish Farming. Water is cultivated for a number of reasons, including food production, fisheries restoration, or for ornamental or other purposes. Modern aquaculture is so diverse that it defies even the most basic of categorizations. What is cultured? Throughout the world, hundreds of species of finfish (think salmon, catfish, trout, and so forth), crustaceans (shrimp and crabs), reptiles and amphibians (alligators and frogs), and mollusks (oysters and mussels) are raised. Why are they cultured? Fish and their aquatic brethren are raised as food, for natural resource management purposes, as pets, as experimental models for biomedical research, and so on. How are they cultured? Fish and shellfish are raised in ponds, tanks, cages or net pens, on floating rafts, and in other systems. Farms and hatcheries are located in open water, land-locked locales, and everything in between.

Perhaps because of aquaculture’s many forms, the public discourse includes a great deal of mis- and disinformation about what aqua-culture is and is not. Is farmed seafood safe to eat? Is wild fish more nutritious than farmed fish? Do hatcheries help or hurt wild fisheries? Don’t fish farms pollute the environment? The media breathlessly delivers negative reports on aquaculture but, facts notwithstanding, rarely reports the benefits and importance of farm- and hatchery-reared fish and shellfish. Aquaculture has been practiced for many millennia, yet remains the most misunderstood means of producing food and other goods for human consumption. Roughly one-half of the seafood we eat comes from farms, and yet many consumers remain hesitant, even resistant to buying farmed fish. Aquaculture is compared with both terrestrial agriculture and capture fisheries and has endured considerable, often unfounded, criticism. Whereas terrestrial agriculture is considered a pillar of civilization, the unin-formed often dismiss aquaculture as an inferior alternative to fishing. More than ever, consumers want to know where and how their food is produced, and like any agricultural sector, the aquaculture industry has worked to address legitimate questions regarding environmental sustainability, animal welfare, and the sociopolitical dynamics of food security. But with so much conflicting information, it is sometimes difficult to know what is true and what is just a fish story. That is why this book exists and, if my guess is correct, why you have picked it up. Understanding Aquaculture will address the common questions and numerous myths surrounding aquaculture and separate fact from fiction. Aquaculture has tremendous promise, but an informed and supportive public is needed to ensure its potential is fully realized. The first part of this book will help familiarize you with aquaculture and how it is practiced throughout the world, and articulate some of the reasons why aquaculture is controversial. The following parts will dive deeper, addressing issues related to the health and safety of farmed fish and shellfish, environmental impacts, and the socioeconomic implications of aquaculture in detail. The concluding part will summarize these subjects and offer thoughts as to why and how we must think about and advocate for sustainable aquaculture.

The precise origins of aquaculture are unknown, likely having been ‘discovered’ by more than one civilization. However, most historians believe aquaculture has been practiced in China for at least several thousand years. Chinese aquaculture began with cultivation of common carp perhaps as early as 2000–1000 BCE (Rabanal, 1988), the mid to late Bronze Age (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Common carp, the first and most widely cultured fish in the world.

By this time, a number of terrestrial animals had already been domesticated, including sheep and goats, cattle, pigs, llamas and alpacas, horses, cats, and, of course, dogs. For context, the first attempts at common carp aquaculture in China likely predated the invention of wheels with spokes, iron-based metals, and the phonetic alphabet. The oldest known monograph describing the cultivation of fish, “The Classic of Fish Culture” was written by the Chinese politician, Fan Lai,1 sometime around 475 BCE, meaning that aquaculture had undoubtedly been practiced by Lai, his contemporaries, and their ancestors long before the 5th century BCE.

In Asia and other parts of the world, our long-dead ancestors likely began capturing young fish and fattening them for the table much in the same way that terrestrial livestock were first domesticated. As detailed in the treatise, “History of Aquaculture” (Rabanal, 1988), four scenarios form the basis for how we presume aquaculture arose many millennia ago. According to each of the four complementary theories, observant and enterprising humans began cultivating the water largely for reasons of expediency. The first scenario involves so-called oxbows, the U-shaped lakes that form from the outward-curving bends of rivers as time and erosion work to disconnect them from the main channel. Flood events can rejoin oxbow lakes to their mother rivers, allowing fish and other organisms to move between them. When the waters recede, the corridors of connectivity close and the oxbow is once again separated from the river. For fish stranded in the oxbow, this may be a catastrophe or a stroke of good luck: if the lake dries out completely, all is lost; if not, stranded fish may find refuge from large predators and other dangers of the river, growing large and prolifically. Humans living near the river would almost certainly have known of these rich fisheries and might have begun to artificially recreate the ideal conditions by modifying the embankments of existing oxbows and supplementing the standing stock through periodic introductions of fish.

The second scenario involves seasonal lakes that form in the low-lying areas of tropical regions as flood waters recede following the end of the rainy monsoon season. These lakes could have been similarly improved and supplemented by human communities inhabiting nearby areas. The third scenario extends this concept to coastal regions, where ancient people fishing in pools and coves at low tide may have sought to increase their take by installing traps to keep temporarily stranded fish and shellfish from exiting during the next high tide. In the fourth scenario, humans may have begun cultivating the water to take advantage of the long-standing premium on fresh seafood. Rather than go fishing in inclement weather or at a moment’s notice, servant or peasant classes may have responded to the demands of nobility by holding wild-caught fish in communal water bodies constructed to provide drinking water or defense. Some of the stocked fish would avoid recapture and survive to reproduce and their progeny would be joined by additional fish transferred from natural waters. Each of the theories posits that a population of aquatic organisms is either created or commandeered, and managed – first inadvertently, then through intentional manipulation – to provide greater yields of seafood.

From these humble, perhaps unintentional beginnings, aquaculture grew. By the time of “The Classic of Fish Culture”, common carp aquaculture was well-established in China and continued to be refined over the next 1000 years. Until the late 7th century CE, Chinese fish culturists had focused almost exclusively on common carp. This changed in 618 CE, with the seizing of power by the Li family and establishment of the Tang dynasty. The Li family shared its surname with the common name for common carp. After rearing of the new emperor’s namesake was prohibited, aquaculturists began raising silver carp, bighead carp, grass carp, and others (Rabanal, 1988). Thus, from imperial vanity came the impetus to establish new husbandry methods and the polyculture (that is, rearing multiple species together) practices that dominate Asian aquaculture to this day. Aquaculture was also developing independently or as a result of immigration in other Asian countries as well as Europe well before the modern era. Interestingly, aquaculture does not appear to have developed in any meaningful way in the Americas, Africa, or Australia until after modern-day introductions of the techniques.

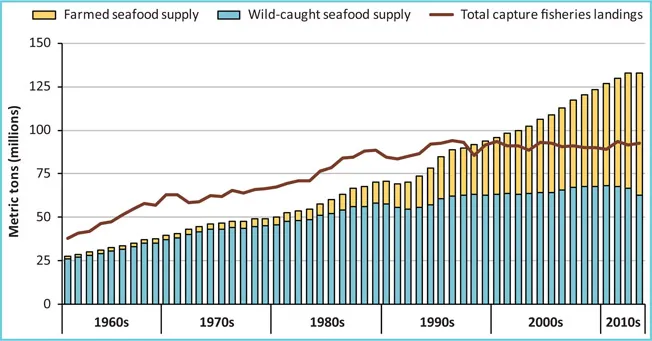

First and foremost, aquaculture was and is an agricultural practice. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations offers a definition that is accordingly agri-centric, defining aquaculture as the “farming of aquatic organisms including fish, mollusks, crustaceans and aquatic plants. Farming implies some sort of intervention in the rearing process to enhance production, such as regular stocking, feeding, protection from predators, and so on. Farming also implies individual or corporate ownership of the stock being cultivated, the planning, development and operation of aquaculture systems, sites, facilities and practices, and the production and transport” (Food and Agriculture Organization, 1988: 37). Until the 1990s, however, aquaculture was a relatively insignificant contributor to the global seafood supplies (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Relative contributions of capture fisheries and aquaculture to world seafood supplies, 1961–2013. As fishing fleets grew in size and in technological sophistication, total fisheries landings, including fish and shellfish used for food and industrial purposes, increased steadily through the 1980s. Thereafter, declining populations and implementation of stricter quotas and regulations on fishing effort have stabilized fisheries landings at roughly 90 million metric tons per year. Consequently, the supply of wild-caught seafood changed little during this time period. In response to ever-growing seafood demand and static supplies of wild-caught product, the aquaculture industry has grown dramatically for decades. Today, more than one-half of seafood eaten throughout the world every year is farmed.

To this point, increasing seafood demand was largely met by increasingly industrialized fishing effort that exploited marine stocks with unprecedented efficiency. The oceans’ bounty, once thought to be an inexhaustible resource, proved no match for human ingenuity and drive and, under the weight of overfishing and environmental change, fisheries contracted and collapsed one after another. In 1974, only 10% of marine fish stocks were considered overfished (harvested in excess of sustainable catch estimates) and 40% were considered underdeveloped; whereas the majority of these fisheries are still considered to be fully, but sustainably fished (a little more than 60%), the relationship between under- (slightly under 10%) and overfished (nearly 30%) stocks has essentially reversed over the last 30 to 40 years (Food and Agriculture Organization, 2014). Capture fisheries landings have held at approximately 90 million metric tons per year since the 1990s, about three-quarters of which is consumed by people. Despite static supplies, seafood demand continues to grow, currently topping more than 130 million metric tons. Dubbed the “seafood gap”, this represents a shortfall of more than 60 million metric tons every year (Food and Agriculture Organization, 2014). Demand for seafood is primarily driven by human population growth. There are more than 7 billion of us scrabbling about on Earth (Population Fund, 2014), and on average we eat a little more than 19 kg (almost 42 pounds) of seafood a year (Food and Agriculture Organization, 2014). Based on recent population growth rates of a little more than 1% per year and static capture fisheries landings, the 60 million metric ton seafood gap increases by more than 2.5 metric tons every minute. That is how much fish, shrimp, and other assorted seafood we all rely on commercial aquaculture to produce.

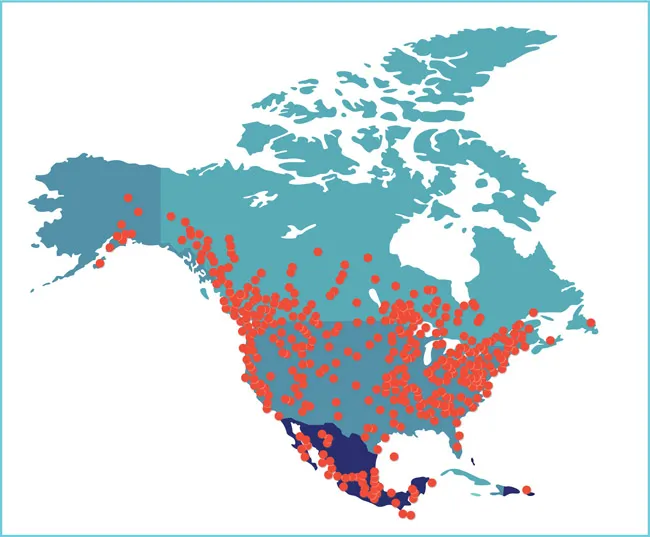

Aquaculture is also a natural resource management activity. Even before marine commercial fisheries began to show the signs of overuse, many freshwater recreational fisheries had slumped and staggered into a state of decline. At the end of the 19th century, many freshwater fisheries in North America had deteriorated as a result of overharvest, habitat modification, and other pressures. In the USA, the US Fish Commission2 was formed in 1871 to determine why fish stocks throughout the country were in decline and, importantly, what could be done about it. One of the Commission’s first goals was to produce and stock shad and salmon in regions where these fish were no longer abundant. The public was eager for technological solutions to societal and environmental problems, and fish hatcheries were viewed as modern marvels that would turn depleted waterways into bountiful sources of food and recreation, eliminating the need for fishing quotas. It was believed that hatcheries would compensate for the effects of habitat degradation, overharvest, and the other fishy woes wrought by man. Many US hatcheries were opened during the golden era of dam construction to seed fisheries in newly created reservoirs and to mitigate the loss of once robust riverine fisheries following the construction of hydropower and water control structures. Hatcheries were built and operated throughout North America with an enthusiasm matched only by our confidence in being able to bend the processes of the natural world to the will of a growing populace (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 Approximate locations of public fish hatcheries engaged in aquaculture for natural resource conservation purposes, including fisheries enhancement and restoration.

For decades, this thinking persisted, even as many fisheries c...