The Dynamics of Human Development

A Partial Mobility Perspective

- 90 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

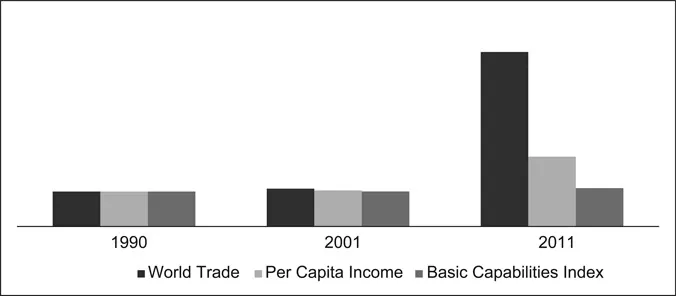

This book studies the dynamic aspects of the Human Development Index (HDI) through a partial mobility perspective. It offers a new axiomatic structure and a set of mobility indices to discuss partial trends and interrogate the human development status at the subgroup and subregional levels. While traditional human development theories are primarily concerned with static distributions corresponding to a point in time, this book looks at an oft-neglected side of HDI and focuses on relative changes in human development that may not be captured by the absolutist framework. In addition, the authors also introduce the concepts of jump and fractional mobility which aid in tracking the development and stagnation among various groups within a population.

This work breaks fresh ground in the study of human development. It will be of great interest to scholars and researchers of economics, development economics, political economy, and development practitioners.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

DYNAMICS OF HUMAN DEVELOPMENT

1.1 Introduction

1.2 A discourse on positional objectivity

(A) The sun is much larger than the moon in size.

(B) From the earth, the sun and moon look similar in size.

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- List of tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- List of abbreviations

- 1 Dynamics of human development: the perspectives of partiality

- 2 Partial mobility: relative changes in human development

- 3 Jump in the dynamics of human development

- 4 Fractional mobility in human development

- 5 Some general issues in the partial mobility of human development

- 6 Conclusion

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app