1.1 Introduction

Marijuana is the most widely used recreational drug in the Western world, and is consumed by ∼3% of the world's population (∼185 million individuals).1 The legal cannabis turnover was ∼$7 billion in 2016 in the United States alone, and it is expected that it will grow to $22 billion by 2021.2 The advent of legalized cannabis in multiple regions of the United States, with currently 28 and 8 States having accepted medical and recreational marijuana, respectively, raises concerns about its potential hazard to health. Nevertheless, research on the therapeutic potential of cannabis extracts-based drugs suggests them to be clinically useful in a wide range of pathological conditions, including neurological3 and psychiatric disorders.4 Conversely, repeated cannabis use has been associated with short-term and long-term side effects, including cognitive alterations, psychosis, schizophrenia and mood disorders,4 as well as respiratory and cardiovascular diseases.5 In this context, the existence of different species and cultivars of cannabis must be taken into account when evaluating the impact on health outcomes. Cannabis sativa and Cannabis indica are the most widespread and best characterized species of cannabis, and their extracts contain phytocannabinoids of therapeutic interest, such as Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD), both shown in Table 1.1. The effect of cannabis extracts depends on the amount of THC and CBD, as well as on the presence and concentration of >110 additional phytocannabinoids, and >440 non-phytocannabinoid compounds like terpenoids, flavonoids and sterols.6 Thus, different cannabis extracts may be different “chemovars” with a different chemical profile, which means that they may contain different components and/or different amounts of them. In addition, the modes of cultivation, harvest, extraction of active principles and administration may further affect the final chemical composition, clearly suggesting that there is no “one cannabis” but several mixtures even from the same plant.3 As yet, there is little understanding of the pharmacological efficacy of cannabis extracts, and these uncertainties represent a warning for the clinical applications of these natural compounds.3 The complexity of the plant extracts is even exceeded by the complexity of the molecular targets that they can hit in our body, as described in the following section.

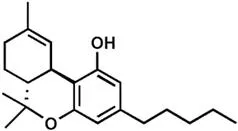

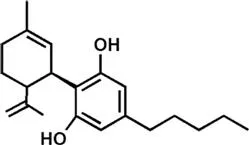

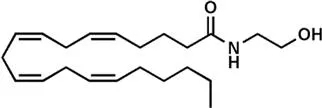

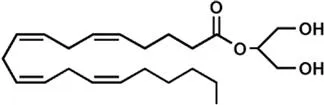

Table 1.1 Chemical structures of the major plant-derived cannabinoids and endocannabinoids.

| Name (abbreviation) | Chemical structure |

| Cannabinoids: | |

| Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) | |

| Cannabidiol (CBD) | |

| |

| Endocannabinoids: | |

| N-Arachidonoylethanolamine or anandamide (AEA) | |

| 2-Arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) | |

1.2 The Complex Endocannabinoid System

It is well established that THC binds to and activates specific G protein-coupled receptors, known as type-1 (CB1) and type-2 (CB2) cannabinoid receptors, that endogenously are triggered by ligands that were identified in the 1990s as anandamide (N-arachidonoylethanolamine, AEA)7 and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG).8,9 These two compounds, an amide and an ester of arachidonic acid, respectively (Table 1.1), are the most active and best studied endocannabinoids (eCBs).5,10 Both molecules are metabolized by a complex array of biosynthetic enzymes, hydrolases and oxygenases, and are transported through the plasma membrane and intracellularly by distinct carriers. Altogether receptors, enzymes and transporters of eCBs form the “eCB system”, that has been recently discussed in a comprehensive review.11

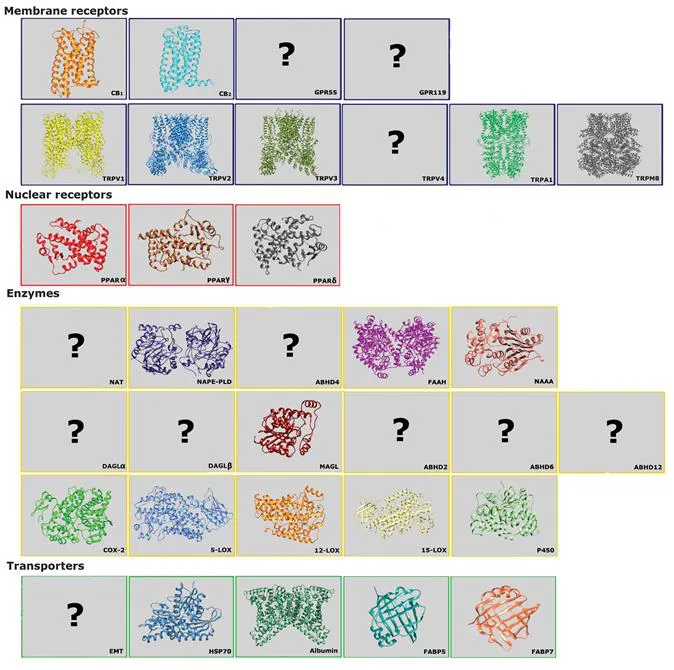

The various components of the eCB system support and control the manifold actions of eCBs, both in the central nervous system10,12 and at the periphery.5 In particular, the number of receptors activated by eCBs in the same cell, both on the plasma membrane and in the nucleus, appears striking. Indeed, the most relevant eCB-binding receptors include: i) CB1 and CB2,13 as well as G protein-coupled orphan receptors (GPR) 5514 and 11915 (all on the plasma membrane and with an extracellular binding site); ii) transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1)16 and additional transient receptor potential (TRP) channels TRPV2, TRPV3, TRPV4, TRPA1 and TRPM8 (all on the plasma membrane, but with an intracellular binding site);17 and iii) nuclear peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) α,18 γ19 and δ,20 that are all transcription factors that regulate gene expression. It is of paramount importance that receptor-mediated activities of eCBs are subjected to a stringent “metabolic control”, which means that their cellular concentration (and hence biological activity) depends on a balance between synthesis and degradation by different biosynthetic and hydrolytic enzymes.11 Among the latter, N-acyltransferase (NAT),21N-acyl phosphatidylethanolamines-specific phospholipase D (NAPE-PLD),22 and α/β hydrolase domain 4 (ABHD4)23 catalyze parallel routes for the release of AEA from phospholipid precursors; instead, fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH)24 and N-acylethanolamine acid amidase (NAAA)25 cleave AEA and other eCBs, terminating their signalling activity. Much like AEA, diacylglycerol lipases (DAGL) α and β synthesize 2-AG,26 that instead is cleaved through different routes by monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL),27 ABHD2,28 ABHD629 or ABHD12.30 In addition to synthesis and degradation, a further level of complexity in eCB metabolism is represented by the addition of oxygen to the fatty acid moiety by cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), lipoxygenases (LOXs) like 5-LOX, 12-LOX and 15-LOX, and cytochrome P450.31 Interestingly, the oxidative products of eCBs are endowed with their own biological activities, distinct from those of eCBs (ref. 32, and references therein). The stringent metabolic control of eCB tone is further modulated by distinct transporters that facilitate the movement of eCBs both across the plasma membrane (via a purported eCB membrane transporter, EMT),33 and intracellularly,34 as well as by storage of eCBs in cytosolic organelles like adiposomes.35 Among the intracellular transporters of eCBs are heat shock protein (HSP) 70 and albumin,36 and fatty acid binding proteins (FABP) 5 and 7.37

To date, 3D structures of 23 out of the 34 major components of the eCB system have been resolved, as shown in Figure 1.1. The remaining 3D structures of 11 eCB system components are still elusive, thus preventing our understanding of their regulation, cross-talk with other eCB system components, and ultimately their impact on eCB signalling.11 This information gap appears particularly troubling for enzymes involved in 2-AG metabolism: out of 6 most important enzymes discovered so far (DAGLα, DAGLβ, MAGL, ABHD2, ABHD6 and ABHD12), only MAGL has a known 3D structure (Figure 1.1).

Fig...