- 197 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Christianity Today:

2018 Award of Merit Christian Living/Dicipleship

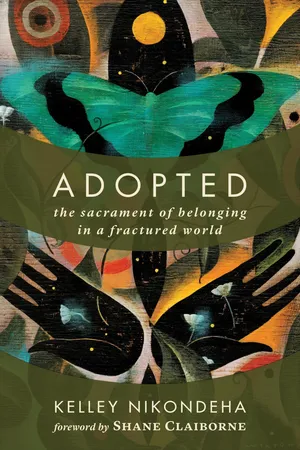

In this compellingly readable book Kelley Nikondeha—adoptive mother and adopted child herself—thoughtfully explores the Christian concept of adoption. Her story and her biblically grounded reflections will give readers rich new insights into the mystery of belonging to God's big family.

In this compellingly readable book Kelley Nikondeha—adoptive mother and adopted child herself—thoughtfully explores the Christian concept of adoption. Her story and her biblically grounded reflections will give readers rich new insights into the mystery of belonging to God's big family.

The Academy of Parish Clergy's 2018 Top Ten Books for Parish Ministry

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Adopted by Kelley Nikondeha in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Ministry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Roots

Back in the Garden of Eden, the epicenter of the cosmos, God reached into the earth to form Adam. All of the biological matter residing in the dark loam, the seeds and soil and nutrients, became part of humanity. Our first biological link is to soil, or so the story goes.

What this original story cracks open for us is the reminder that we are deeply related to creation. We are a swirl of soil and seeds, skin and bone, divinity and mystery. It is good to remember that we belonged to a place before we belonged to a people.

Out of the Garden and into the wider landscape of Scripture, we begin to see those stories of our origins unfold. Beyond clan and tribe, something curious takes hold. Complexity forms at the fringes of bloodlines, and we witness something elusive yet generative at work. Family bonds are created within tribes but also completely apart from them. The tendrils of filial connection are reaching out beyond national borders and twining around different ethnicities to shape a more expansive family.

When it comes to describing belonging in Scripture, family is the metaphor of choice. Adam and Eve are the original family generating from the heart of the Trinity. The Holy Family enters the scene in the Gospel accounts. Between them are generations of families with tangled stories of fidelity and estrangement, barrenness and birth, sibling rivalries and reconciliations. It is through this metaphor that we witness belonging.

When I was a child, every Sunday morning found me sitting with other kids in a semi-circle on the carpet in the fellowship hall of St. Nicholas Catholic Church. We listened, eyes wide, as our Sunday school teacher told stories out of the big illustrated Bible. Like an oscillating fan, she’d move back and forth to ensure we could see all the heroes and heroines in water-colored action. We craned to catch a glimpse of Miriam dancing across the Red Sea, Joseph strutting in his technicolor coat, David with his slingshot, Queen Esther on her throne.

Though we were thousands of years apart, I still knew I was born into the world like them, even Esther, who was “born for such a time as this.” I also knew that my mother wasn’t the one who delivered me so much as the one who received me. Perhaps this explains my attraction to the life of Moses, both a liberator and an adopted child—he embodied a belonging that was familiar to me. My mother didn’t pull me out of a river, but I imagined the current that brought me to her was just as mystical and intentional. Like the other children clustered around the great big book every Sunday, I looked to see where I fit into God’s story.

My own story positioned me to notice adoption at work in Scripture. I saw it not as an invisible metaphor to be unearthed, but as a dynamic to be recognized. In Scripture, adoption meddles with genealogies, subverts oppressive empires, secures imperial inheritances, and opens new possibilities for who can be family. Fracture opens the narrative, and adoption isn’t far behind as a means of repair and integration. As an adult I remain convinced that in order to understand the biblical exploration of belonging, we must include the metaphor of adoption. When I listened to each biblical family story told by my Sunday school teacher, what I intuitively suspected was confirmed—blood isn’t thicker than water. When you factor in adoption, bloodlines don’t have the final say in who belongs in your family. Belonging, not blood, is definitive.

Idelette sat on the red couch in her Vancouver living room, sipping rooibos tea from her homeland. In the bright morning sunlight, we spoke of adoption’s healing potential in the world. It wasn’t an uncommon conversation for us. We had met in Kenya at the Amahoro Gathering, a conversation my husband Claude and I host for African thinkers and practitioners. And ever since, she and I had been talking about Jesus, justice, and our long walk to freedom.

“I want to offer better language for those in the company of the adopted,” I told her over my cup of red tea. “I want to expand our conversation about adoption so that we understand its formative work in us and, by extension, in the world.”

“I want to be a part of that conversation,” she chimed in as she walked toward the kitchen. “After all, I’m adopted, too!”

For the record, Idelette is not adopted in the primary sense of the word. She knows it; I know it. But she insisted, “Paul says that God adopts us—that would make me adopted, and so your conversation would matter to me.” She pulled the blueberry muffins out of the oven, plated them, and offered them to me. But by now I was feeling defensive, unable to return her easy smile or enjoy the muffins.

Yes, Paul did employ the language of adoption in his letters, but to a different effect, I assured her. “It’s as if you are adopted by God. It’s a simile, really,” I insisted.

She broke open a muffin in her hands. “I’m pretty sure I’m adopted by God,” she said, taking a bite and catching a crumb with her finger.

In that moment she became a trespasser, and I was determined to defend my birthright. I didn’t have a biological leg to stand on, but I was a full-fledged member of the company of the adopted. She could learn from my adoptive experience but not claim it as her own. Her insistence was an invasion.

It would be many months later, when the two of us were sitting in my living room, before I could tell her, over a plate of hummus and carrots, that she was right. I had spent the better part of my summer in Burundi following the adoption metaphor throughout Scripture and studying Paul’s letters to discover what she intuitively knew. Paul didn’t soften adoption into a simile; he used the full force of metaphor. We are all adopted by God. Theologically, Idelette and I are both adopted children.

In a temporal sense, I am adopted and she is not. I was relinquished by my first mother and never knew my father, and I don’t know my family’s medical history. I’ve learned how to be a daughter without reflecting my adoptive parents’ likeness in the mirror. This is part of the adoptive experience I alone know, one that Idelette can’t completely embody. And that’s why I felt the heat of offense when she first mentioned a shared sacrament.

But ontologically we do share this sacrament of belonging. Paul says that the spirit of adoption has been given to each of us, making us daughters of God and sisters to one another. And I know something in me had to change in order to acknowledge that truth. Maybe it was hard for me to imagine adoption without relinquishment, to allow Idelette to step into the redemptive arc of belonging without the loss. But I cannot bar God from generosity. The Father gives good gifts, even adoptive ones, to others. My own understanding of the company of the adopted was too narrow. I couldn’t hoard the sacrament of belonging any more than the Hebrews could hoard daily-given manna. If I tried to keep the adoptive goodness to myself, I’d betray the generosity of our Father.

A friend once said to me that when you read the Apostle Paul’s letter to the Romans at a certain slant, it almost looks like God adopted Abraham.1 This elder of Ur, plucked out of genealogical obscurity to be God’s own, becomes an “ancestor of all who believe” by another divine orchestration. Abraham becomes “as if” he were God’s firstborn, with the privilege, the blessing, and the vast promise of an inheritance. It’s grown on me, this idea of Abraham being “as if adopted” by God, providing my imagination with another window to view God’s limitless capacity to forge belonging beyond our natural boundaries.

In his letter to the Roman church, Paul described how God’s family underwent a deep transformation. There was a time when Israel—and only Israel—could be described as the children of God. They alone bore the mark of circumcision, a sign of their covenant with God, setting them apart as God’s unique people on the earth. They possessed the Law, the history, and the genealogy back to Abraham. Israel’s lineage was uncontested.

The advent of Jesus changed all this. No longer did Israel have pride of place among the tribes of the earth, doling out the blessings for lesser nations. Now the uncircumcised were circumcised not by the knife, but by keeping God’s covenant. There was no longer a distinction between Jews and Greeks, said the apostle.

In showing us this family makeover, Paul points to Father Abraham’s story. He recounts how Abraham acted in faith before he was circumcised and God reckoned him as righteous—just like that—in his uncircumcised condition. Only after the reckoning was Abraham circumcised. Why? So that Abraham would become our common ancestor, the father to all who believe. He has uncircumcision in common with some, circumcision in common with others, but what holds this expanded family together is faith. According to Paul, we belong to each other, a family shaped by faith, not physical marks.

Reading in Paul’s letter, we learn that all of Abraham’s descendants in faith will share in God’s promised inheritance. For that initial Roman gathering of believers, nothing would have been more coveted than a real inheritance. And now both Jews and Greeks will share in Abraham’s promise and inherit the world—as long as they believe in this God. Biology, it seems, has shifted in importance for the family of faith.

Lean across the generations and hear Abraham’s echo in Isaiah—eunuchs and foreigners find a place in the New Jerusalem if they keep God’s covenant and keep the Sabbath. God’s family continues to grow, moving beyond tribe and clan. Lean in further still, and your ear might catch the words of the God who prefers Jacob to Esau, Abel’s sacrifice over Cain’s, the One willing to subvert birth orders, dismantle hierarchies, and dethrone patriarchy. This is the very One who reimagines genealogies, weaving in the abused and outcast Tamar, Rahab the Canaanite prostitute, and Ruth the Moabite to form a family that reflects the Father’s own diverse and generous image.

From the faith of Abraham to the unorthodox genealogies, the Apostle Paul reveals the truth hinted at throughout the generations—we belong by believing, not by biology. All who believe, all who keep covenant, all who want in can be grafted into this family tree. As our eyes open, we begin to see a more expansive kind of family. By comparison, our notion of family, defined by bloodlines and ethnicities, begins to look narrow and far too exclusive to resemble God’s largess.

Abraham’s story is only the beginning of the adoption narratives we unearth in the biblical root system. Arcane adoption formulas are embedded in the Hebrew Bible. In Genesis we overhear Rachel planning the adoption of the child of her maid, Bilhah, as she commands Jacob to “. . . go in to her, that she may bear upon my knees and I too may have children through her.”2 We witness the patriarch Joseph adopting his grandchildren, born in Egypt, so that they will be full heirs of Israel,3 with the same formula: “. . . born on Joseph’s knees.” The image is that of a father putting the children on his knees, admiring and acknowledging these as his kin. Much later, in the book of Ruth, it is Naomi, a full-blooded Israelite, who brings her grandson “. . . and [lays] him on her bosom” to ensure he will not be left out of the lineage due to the foreign status of his mother, Ruth, a Moabite.4

When I read through these histories, it seems to me that Israel had a tradition of adoption. Whether to address a foreign birth or a foreign mother, adoption ensured children belonged to the tribe and would not be disinherited. Adoption was a remedy of sorts. According to the stories of Scripture, it both meddled in and mended families.

If God writes straight using crooked lines, as Desmond Tutu says, has God’s intended family been taking shape by unexpected means all along?

On Epiphany Sunday a few years ago, I took one last look at the manger scene perched on the altar of the local cathedral in my neighborhood. Joseph knelt over his newborn son. Like any other father, he looked astonished at the strength of his wife, mesmerized by the arrival of this child. In this adoption scene, a father on his knees received a son as his own. This was how Joseph first experienced fatherhood. And it was through the story of Joseph that I first recognized Jesus as the Adopted One.

God rooted his own Son into the biblical story as the son of David and a son of Abraham through Jesse’s son, Joseph. His divine paternity would be known only to a few—for the moment. In the Gospels we learn of the divine intervention and the human agency involved in the birth of Jesus. God created belonging through both biological and adoptive means.

Early on in her pregnancy, Mary knew this child was somehow set apart. The angel Gabriel made that clear (that is, as clear as possible, given the shift req...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword, by Shane Claiborne

- Introduction

- 1. Roots

- 2. Relinquish

- 3. Receive

- 4. Reciprocate

- 5. Redeem

- 6. Repair

- 7. Return

- 8. Relatives

- Notes

- Acknowledgments