![]()

Part One

DESCRIPTION

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Miracles of Belief:

The Orthodox Covenant with Icons

We confess and proclaim our salvation in word and images.

—KONTAKION FOR

“THE TRIUMPH OF ORTHODOXY”

The last place one might expect to encounter Christians praying with icons is a theology classroom in a Calvinist school. John Calvin, after all, firmly rejected the usefulness of images for the purposes of worship. But such is the widespread fascination with icons across the Christian spectrum that students at Calvin College have shown interest in such an encounter. A theology professor’s January-term course on iconography, cotaught with an area iconographer, has attracted its fair share of student interest, introducing students to practices associated with making and using icons and orienting students to the theology out of which they come. In my own Presbyterian congregation in Santa Barbara, amateur artists have taken to icon painting. The large Episcopal congregation in downtown Santa Barbara has offered icon-painting seminars.1 You can probably think of similar examples from your own experience.

What should we make of all this interest in icons? Curiosity about icons is in part the by-product of the rediscovery, over the last few decades of the twentieth century, of the Eastern Orthodox Christian tradition by non-Orthodox American Christians. Of all the varieties of Christianity in the United States, the Eastern Orthodox churches were until recently the least visible, least accessible, and most “exotic.” But that has changed.2

The Context: Authorizing the Icon

Missions, Immigrants, and Converts

Orthodoxy arrived in North America in the eighteenth century with Greek settlers in Florida and Russian missionaries in Alaska. But these small Orthodox communities were the exception rather than the rule for patterns of immigration and mission in North America. Scholars estimate only fifty thousand Orthodox Christians in the United States at the turn of the twentieth century. By the end of the century, however, that number had climbed to at least 1.2 million (though some estimates go well beyond this number).3 Some of this increase is due to immigration—especially intense around the middle of the century with the establishment of Communism in much of eastern and central Europe.4 Even with these increased numbers, however, as a proportion of the overall population of the United States, Orthodox Christians remain a tiny minority. Immigration alone can’t fully account for the growing awareness of Orthodoxy among American Christians at large.

Protestant and Catholic conversions to Orthodoxy have certainly helped increase awareness.5 Perhaps the most spectacular example of this dynamic, as narrated by the now-Orthodox priest Peter Gillquist, occurred in 1987 in Southern California. Beginning in the late 1960s, a group of evangelical Christians based in Santa Barbara, most of whom had roots in the parachurch organization Campus Crusade for Christ, dedicated themselves to re-creating what they called “the New Testament church.” Through study and prayer, over the course of about a decade, the community inched closer and closer to Eastern Orthodoxy. Resisting the idea of forming a new denomination, they first organized themselves as the New Covenant Apostolic Order. Further study convinced the community that an “order” can’t really exist independently from a church; a few years later, the New Covenant communities reorganized as a denomination of sorts, the Evangelical Orthodox Church. In time, this formal identification with Orthodoxy led to a desire to be properly united to the Orthodox Church, and in the spring of 1987 seventeen Evangelical Orthodox congregations in Southern California officially joined the Antiochian Archdiocese of North America.6 Peter Gillquist’s journey, and that of his fellow travelers, brought Eastern Orthodoxy into the spotlight for many American evangelicals.

Then, in 1992, Frank Schaeffer, the son of prominent evangelical author Francis Schaeffer, joined the Orthodox Church. Subsequent affiliations have drawn further attention to Orthodoxy—Frederica Mathewes-Green, a Christian author and columnist, left the Episcopal Church for the Orthodox Church in 1993; Yale University church historian Jaroslav Pelikan, a prominent scholar in Lutheran circles, joined in 1998. Other, less publicly known figures, like Englishman Timothy Ware, now Metropolitan Kallistos Ware, also played important roles in raising the profile of Orthodox Christianity in the English-speaking world. Ware is the author of the best-selling general work on Orthodoxy in the English language, The Orthodox Church.7 John Maddex, a former associate of Moody Radio, went on to found Ancient Faith Radio, which operates under the auspices of the Antiochian Orthodox Archdiocese of North America. Ancient Faith Radio has greatly increased the accessibility of Orthodoxy in North America and far beyond.

The real story, though, doesn’t lie with this list of individuals. It lies with the large number of ordinary American Christians who have “traveled the road to Constantinople.” Today, in congregations associated with the largest Orthodox body in the United States, the Orthodox Church in America, over 50 percent of the parishioners and nearly 60 percent of current and future priests are converts to Orthodoxy. Though numbers of noncradle Orthodox are smaller in the more ethnically oriented Greek Orthodox Church, they are still significant: 29 percent of parishioners, 14 percent of current priests, and 26 percent of seminarians were not born into Greek Orthodoxy.8

The Recovery of the Icon

One need not become Orthodox, however, to deepen one’s appreciation for Eastern Christianity. On the scholarly level, the liturgical renewal movements of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, which culminated in both the Catholic Church’s Second Vatican Council and the midcentury ecumenical movement, were animated by renewed attention to patristics, that is, to the writings of the ancient church fathers at the core of Orthodox theology.9 Returning to the primary sources that gave shape to all streams of the Christian faith fostered renewed attention to the riches of Eastern Christianity.

On the popular level, we need only note the avalanche of books on icons that has appeared over the last couple of decades to appreciate the level of interest and curiosity that now exists for this formerly obscure (in North America, at least) Christian art form.10 Something has changed indeed when the former archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, publishes two books on praying with icons!11 But then again, Williams is himself a child of the liturgical renewal movement. He studied patristics as a student, wrote his PhD thesis on the theology of twentieth-century Orthodox theologian Vladimir Lossky, and today serves as a patron for the Fellowship of Saint Alban and Saint Sergius, an Oxford-based organization dedicated to “fostering dialogue among Christians East and West.”12

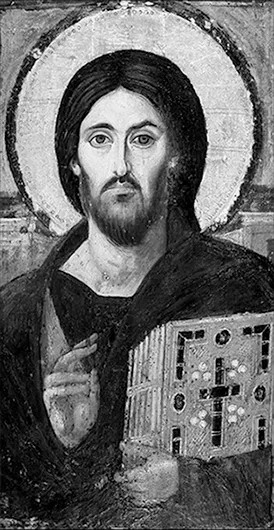

Fig. 6. Icon of Christ, Monastery of Saint Catherine, Sinai. Sixth century.

It was Vladimir Lossky, the subject of Williams’s 1975 thesis, who helped make icons and their theological framework more easily accessible in the West. Lossky was one of many Russians who fled their homeland after the 1917 revolution and eventually settled in Paris. With his fellow expatriate, iconographer Leonid Ouspensky, Lossky published The Meaning of Icons in 1952, the first major study of icons available in English that took into account not only their artistic aspects but also their theological import.13 This work, as one reviewer put it, “has done more than any other single book for the study and appreciation of icons in the twentieth century.”14

Parallel to Lossky’s work, Princeton art historian Kurt Weitzmann brought to light for the English-speaking world some of the oldest surviving icons we know of. Though it is hard to believe, the now familiar and beloved sixth-century icon of Christ from the Monastery of Saint Catherine (fig. 6) was not reproduced or properly catalogued until the mid-1950s when it was first included in a French study by a Greek scholar. It wasn’t published in color in its restored state until Weitzmann’s study of the Sinai icons was released in 1976.15 The work of Ouspensky, Lossky, Weitzmann, and other scholars during the second half of the twentieth century began a renewal of the iconic tradition that continues to this day.

While immigrant Orthodox Christians always had access to the icons in their homes and churches, these icons varied in quality and sometimes in canonical correctness. The new scholarship on icons gave American Orthodox Christians a richer, fuller understanding of their own tradition. For non-Orthodox American Christians who had little or no regular access to actual icons, it made accessible a wealth of information about icons that was entirely new to them. Though the primary audience for all this new work was scholarly, popular interest soon caught up, which makes the late twentieth-century tidal wave of fascination with icons—branded by one irritated Mennonite as “iconitis”—a bit more comprehensible.16

Orthodox believers, though, would see more in all this than just the currents of research and scholarship bearing fruit. They would see the power of icons themselves at work.

Authorizing the Icon

Icons, as understood by the Orthodox, are no mere pictures. They are “windows to heaven,” “sacred doorways,” “the gospel in line and light,” “theology in color.” They do not represent; they make present. And what they make present are Christ and the fully perfected and transfigured saints in communion with Christ as well as the salvific events of the church’s past and future. It comes as no surprise to an Orthodox Christian that anyone longing for hope, for beauty, for compassion, for the transcendent, would be drawn to icons. Icons, it is said, convert. There are even “iconic” instances of this effect. In my interviews with iconographers, I heard more than once how the exercise of painting an icon, even if done by a skeptical atheist, can result in conversion to faith. This is exactly the account given for Leonid Ouspensky’s conversion in Paris in the 1930s.17 The claim is not new. It’s difficult to find a book on Orthodoxy that does not recount the story of the conversion of the Slavic Rus’ people to Orthodox Christianity in 988, inspired by the splendid music and image-rich liturgy in Constantinople: “We knew not whether we were in heaven or on earth. For on earth there is no such splendor or such beauty, and we are at a loss how to describe it. We only know that God dwells there among men, and their service is fairer than the ceremonies of other nations. For we cannot forget that beauty. Every man, after tasting something sweet, is afterward unwilling to accept that which is bitter, and therefore we cannot dwell longer here.”18 The efficacy of icons as mediators of divine presence parallels many Protestant Christians’ understanding of the power of inspired Scripture to convert readers to Christ.

Books on icons typically begin with a theological discussion that immediately transports us back over twelve hundred years. Unlike Protestant arguments about art in the church, which are typically located in the 1500s, and unlike Catholic arguments, which are located in mid-twentieth century, Orthodox arguments about art in the church were considered settled by the middle of the ninth century. A handful of foundational texts outline the basic contours of the argument: the writings of John of Damascus (c. 676–749); those of Theodore the Studite (759–826); and the pronouncements of the Seventh Ecumenical Council, which took place at Nicaea in 787 (also known as the Second Council of Nicaea). These sources present the legitimacy of images as a matter of fundamental importance for Christian faith properly understood, that is, of a truly orthodox faith. According to this line of argumentation, to deny the possibility and legitimacy of an image of Christ—and by extension, his saints—is tantamount to denying the incarnation. Denying the incarnation invalidates the heart of Christian belief. Ouspensky, in explicating this intersection of image, theology, and orthodoxy, cites an additional historical source, the ancient Athanasian hymn sung in honor of the triumph of Orthodoxy:

No one could describe the Word of the Father;

but when he took flesh from you, O Theotokos [God-Bearer]

he consented to be described,

and restored the fallen image to its former state

by uniting it to divine beauty.

We confess and proclaim our salvation in word and images.19

This hymn contains the basic elements of the entire theological system upon which icons rest: Christ’s divinity, as is the case with the Godhead, is indescribable; but Christ in his incarnation allowed himself to be circumscribed in flesh, which can be depicted; in becoming flesh and consenting to be so circumscribed, Christ effects our salvation by redeeming us in our flesh; and does so by uniting us to his own divine beauty. Ouspenksy glosses this hymn with a saying from the church fathers, “God became man so man might become God,” thereby making explicit the analogy between the Orthodox understanding of icons and the Orthodox doctrine of theosis—the complete eschatological realization of all Christians into the full, divine likeness of Christ.20 Icons are a crucial fulcrum in this economy of salvatio...