- 171 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

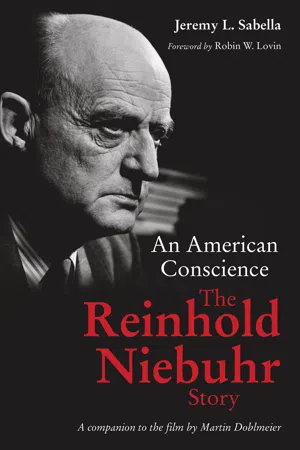

Reinhold Niebuhr (1892–1971) was an inner-city pastor, ethics professor, and author of the famous Serenity Prayer.

Time magazine's 25th anniversary issue in March 1948 featured Niebuhr on its cover, and

Time later eulogized him as "the greatest Protestant theologian in America since Jonathan Edwards." Cited as an influence by public figures ranging from Billy Graham to Barack Obama, Niebuhr was described by historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. as "the most influential American theologian of the twentieth century."

In this companion volume to the forthcoming documentary film by Martin Doblmeier on the life and influence of Reinhold Niebuhr, Jeremy Sabella draws on an unprecedented set of exclusive interviews to explore how Niebuhr continues to compel minds and stir consciences in the twenty-first century. Interviews with leading voices such as Jimmy Carter, David Brooks, Cornel West, and Stanley Hauerwas as well as with people who knew Niebuhr personally, including his daughter Elisabeth, provide a rich trove of original material to help readers understand Niebuhr's enduring impact on American life and thought.

CONTRIBUTORS (interviewees)

Andrew J. Bacevich

David Brooks

Lisa Sowle Cahill

Jimmy Carter

Gary Dorrien

Andrew Finstuen

K. Healan Gaston

Stanley Hauerwas

Susannah Heschel

William H. Hudnut III

Robin W. Lovin

Fr. Mark S. Massa, SJ

Elisabeth Sifton

Ronald H. Stone

Cornel West

Andrew Young

In this companion volume to the forthcoming documentary film by Martin Doblmeier on the life and influence of Reinhold Niebuhr, Jeremy Sabella draws on an unprecedented set of exclusive interviews to explore how Niebuhr continues to compel minds and stir consciences in the twenty-first century. Interviews with leading voices such as Jimmy Carter, David Brooks, Cornel West, and Stanley Hauerwas as well as with people who knew Niebuhr personally, including his daughter Elisabeth, provide a rich trove of original material to help readers understand Niebuhr's enduring impact on American life and thought.

CONTRIBUTORS (interviewees)

Andrew J. Bacevich

David Brooks

Lisa Sowle Cahill

Jimmy Carter

Gary Dorrien

Andrew Finstuen

K. Healan Gaston

Stanley Hauerwas

Susannah Heschel

William H. Hudnut III

Robin W. Lovin

Fr. Mark S. Massa, SJ

Elisabeth Sifton

Ronald H. Stone

Cornel West

Andrew Young

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access An American Conscience by Jeremy L. Sabella in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religious Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

The Preacher-Activist

On a Sunday morning in August of 1915, a fresh-faced minister ascended to the pulpit at Bethel Evangelical Church in Detroit for the first time. He felt the mismatch between his youth — he was just twenty-three — and the weight of the task before him. “Many of the people insist,” wrote Reinhold in the opening entry to his published diary, “that they can’t understand how a man so young as I could possibly be a preacher.”

But the new pastor was not only concerned with how he was perceived; he also chafed at the trappings of the pastoral role. “I found it hard the first few months to wear a pulpit gown,” he noted. “I felt too much like a priest in it, and I abhor priestliness.” Yet he also learned to value the platform his vestments afforded him: “It gives me the feeling that I am speaking not altogether out of my own name and out of my own experience but by the authority of the experience of many Christian centuries.”1

Reinhold was no stranger to this sort of ambivalence. He felt it two years earlier, in the spring of 1913, when his father, the Reverend Gustav Niebuhr, passed away suddenly. At twenty years of age, Reinhold stepped in and served as interim minister. He also felt it when, a few months later, he enrolled at Yale Divinity School. He reported feeling like a “mongrel among thoroughbreds” as he struggled to fit in socially and master the academic nuances of the English language.2 Yet from his rough-hewn prose, a brilliance showed forth that set him apart from his classmates. He received a scholarship that allowed him to earn a master’s degree the following year.

In the summer of 1914, the siren song of politics nearly lured Reinhold from his studies. Carl Vrooman, a family friend who worked as assistant secretary of agriculture under Woodrow Wilson, had offered him a salaried job as his assistant in Washington. This prospect appealed to Reinhold’s native interest in politics, and also would have supplied financial resources with which he might support his widowed mother and younger siblings. He eventually declined the offer, but not without a good deal of soul-searching.3 Upon earning his master’s degree, Reinhold accepted a pastoral position at Bethel Evangelical Church in Detroit, which belonged to a German-language denomination known as the German Evangelical Synod. His mother, Lydia, moved into the parsonage, where she took over the church’s administrative duties. This freed Reinhold to cultivate and pursue the political life he had originally set aside.

As Reinhold adjusted to his pastorate, there was little to predict what lay in store for his congregation, or the city of Detroit, or the pastor himself. By the time he left, thirteen years later, to accept a position on the faculty of Union Theological Seminary in New York City, Bethel had grown exponentially; the population of Detroit itself had nearly tripled in size; and Reinhold had established himself as one of the most incisive and provocative thinkers in American Christianity. In the intervening years, Niebuhr would support and then critique American involvement in the First World War, collaborate with the Catholic and black communities of Detroit to take on a resurgent Ku Klux Klan, and publicly confront Henry Ford for unjust labor practices.

It is during the Detroit years that Niebuhr cultivated the ability to manage the divergent interests, identities, and responsibilities that converged uneasily in his life: his German heritage and his American identity; the life of faith and the life of the mind; his youthful inexperience and the authority of the pastoral role; his passion for social justice and the quotidian responsibilities of running a church. In the process, Niebuhr exposed the illusory nature of the dichotomies that others took for granted: between church and world, faith and intellect, religion and politics, the vocation of the pastor and the life of the activist. This sheer breadth of social engagement enabled Niebuhr to speak to his context in uniquely insightful, compelling, and unsettling ways.

The triumphs and tribulations of Niebuhr’s time in Detroit shaped the content and tone of his first major book, Moral Man and Immoral Society (1932). It lambasted both religious and secular variants of liberalism, polarized intellectual leaders, and catapulted Niebuhr to national prominence. As Niebuhr looked back on his legacy late in his career, he noted that his Detroit years “affected my development more than any books I might have read.”4 Thanks to Niebuhr’s time in the Motor City, religion in American public life would never be the same.

Taking Dead Aim at Ford

Imagine, for a moment, life in rural America at the dawn of the twentieth century. Farmers still relied on draft power to plow their fields and on kerosene lamps to light their homes. At any sizable distance from the railroad network, one traveled more or less the same way that people had done for centuries: by horse and buggy. For all the innovation emerging in large urban centers, rural life followed the same basic contours that it had for the Puritans and the pioneers. In the eyes of the vast majority of Americans, the “horseless carriage” was a plaything for the wealthy that smacked of decadent impracticality.

Then in 1908 came Henry Ford’s Model T. It was mechanically reliable, simple to operate and fix, and designed to navigate the rough countryside terrain. The vastly improved efficiency of Ford’s assembly line enabled him to mass-produce the Model T at an affordable price. And thanks to tractor conversion kits, the Model T could be put to use as a powerful and versatile piece of farm equipment. From urban centers to small-town America, Ford’s invention revolutionized American life. At the same time, Ford created a reputation as a benevolent employer, most famously through his creation of the then-impressive five-dollar-per-day wage. It is little wonder that the public held him in such high esteem: he had provided ordinary Americans with unprecedented mobility and convenience and had created thousands of good jobs in the Motor City.

Niebuhr, however, was less than impressed with the cult of Henry Ford. In a series of scathing articles published in the premier religious magazine of the day, the Christian Century, Niebuhr took dead aim at Ford, marveling that the public held him in such high esteem “even though the groans of his workers can be heard above the din of his machines.”5 In general, Niebuhr’s arguments were met with a mixture of apathy and incredulity. Few people were willing to attack the man who provided so many Americans with cheap cars and high-wage jobs. Indeed, Niebuhr himself had benefited from Ford’s success. The construction of a substantially larger building for his congregation relied in no small part on the generosity of parishioners who had become financially successful through their association with Ford. As Gary Dorrien, who holds the Reinhold Niebuhr Chair at Union Theological Seminary points out, Niebuhr was broadly perceived as criticizing the “goose that was laying the golden egg.”6

Niebuhr was aware of these dynamics. Years of experience had taught him that even the mildest critique of Ford would be met with torrents of criticism. Yet he felt obligated to take Ford on. Ford’s track record — his curious compound of idealism and cutthroat business practices; his presumption that his personal morality ensured the morality of his enterprises; and the way that he used his philanthropy to cultivate a reputation as a humanitarian, even as he squeezed his workers for ever greater profit — epitomized something essential about the American character. Thus, for Niebuhr, the Christian Century articles were not just a critique of Ford, they were a test of America’s religious conscience.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a liberal Christian movement called the Social Gospel had transformed American Christianity. The Social Gospel called on Christians to establish the kingdom of God on earth by reforming oppressive economic systems. Social Gospel leaders took an optimistic view of human nature, focusing less on human fallibility than on the ability of good-hearted individuals to work for social justice. If Niebuhr could expose the problems with Fordism in a way that resonated with the general public, then perhaps the Social Gospel strategy of appealing to people’s moral sensibilities could bring about broader social change. But if his efforts failed, then perhaps liberal Christianity fundamentally lacked the wherewithal to confront the unprecedented social challenges of a rapidly industrializing society.

Niebuhr’s standoff with Ford helped generate the searing critique of liberalism in general and liberal Christianity in particular that Niebuhr developed in Moral Man and Immoral Society. Indeed, one could make the case that his career and legacy would have looked quite different had he not decided to take on arguably the most popular and influential figure of his day. How did this confrontation come about? The answer to this question has its roots in the early days of Niebuhr’s ministry, when his adopted nation and his ancestral nation took opposite sides in the First World War.

A Crisis for German Americans

The prospect of US involvement in the First World War presented a crisis for the German immigrant community. On the one hand, supporting the American war effort became a way for German Americans to demonstrate their bona fides as good US citizens. On the other hand, fighting against the country of their ancestry felt like a betrayal. It is no surprise that a German American church would feel this tension very acutely — or that their pastor would feel compelled to address it.

In his first article to be circulated nationally, Niebuhr came out strongly in favor of the war effort. “The Failure of German-Americanism”

was published in the Atlantic in July of 1916.7 In the years following its publication, he would retract or revise nearly every position he took in this piece; however, the article showcased a passion for social justice and a capacity to critique his own communities that Niebuhr would exhibit throughout his career. In this respect, it foreshadowed what was to come.

was published in the Atlantic in July of 1916.7 In the years following its publication, he would retract or revise nearly every position he took in this piece; however, the article showcased a passion for social justice and a capacity to critique his own communities that Niebuhr would exhibit throughout his career. In this respect, it foreshadowed what was to come.

In this article, Niebuhr argued that the German American strategy for addressing the so-called “problem of the ‘hyphen’” was not working. Like every immigrant community, that of German Americans had to figure out how to navigate the tension between two divergent impulses: the need to assimilate to a new society and the need to remain connected to its cultural heritage. German Americans opted to absorb American culture while retaining robust German-language traditions, as was clear in their insistence on maintaining German-language churches. However well this balancing strategy might have worked initially, it was no longer feasible as the prospect of war with Germany loomed over American public life. The coming war would force the German American community to break with its hyphenated identity by choosing which identity would predominate and which would become subordinate. By supporting the American cause, Niebuhr moved decisively in favor of an American over a German identity.

On Niebuhr’s reading, assimilation had proven difficult in part because of clashes between American and German value systems. German virtues were “individualistic rather than social,” as manifested by wealthy immigrants who were “prone to attribute all poverty to indolence and to hold the individual completely responsible for his own welfare.” This German paradigm contrasted with progressive trends in American society whereby the “obligations of the individual toward the welfare of his fellow man and society as a whole have been considerably widened, and the moral conscience of the whole nation has been made more sensitive.”

The tension between these moral sensibilities came to a head as the American temperance movement reached its peak. Beginning in the early nineteenth century, temperance advocates had lobbied for the American government to limit or entirely prohibit the sale of alcohol, which they believed was at the root of social ills ranging from poverty to domestic violence. Prohibition, or the movement to make alcohol sale illegal, pitted American Christians against one another, as newer evangelical sects like Baptists and Methodists advocated complete abstinence from alcohol, while Catholics and older European Protestant groups urged moderation, not teetotaling. The contrast in Christian opinions was instructive for Niebuhr. In his Atlantic article, he argued that German Americans opposed Prohibition on individualistic grounds that on closer inspection functioned as a means of evading moral responsibilities toward society: “[German Americanism] claims to be fighting for ‘personal liberty,’ a principle that has, in the history of civilization, covered a multitude of sins in the mantle of respectability.” In the name of preserving their personal right to imbibe, German Americans were prepared to oppose the sort of legislative action necessary to address the multitude of social ills that had alcohol consumption at their root.

The way that Niebuhr contrasted a German affinity for individualistic virtues with an American affinity for social virtues illustrates how immersed he had been in the Social Gospel. At the movement’s theological core was the belief that the kingdom of God described in the Christian Bible had concrete social implications. By carrying out the gospel’s precepts to care for those on the margins of society, and by fighting unjust structures and practices, Christians would fulfill their mandate to build the kingdom of God on earth.

The Social Gospel movement had far-reaching cultural impact: it energized liberal Protestantism, instilled and deepened social consciousness at various levels of American society, and helped catalyze some of the most important social reform efforts and organizations of the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Progressive Era, including women’s suffrage and Prohibition, Alcoholics Anonymous, and the YMCA. Indeed, some scholars have described the Social Gospel movement as the Third Great Awakening, similar in scope and impact to the colonial-era religious revivals of the Great Awakening and the frontier-transforming religious revivals of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Niebuhr’s complaint that German Americans emphasized individual morality and material success at the expense of recognizing their obligations outside of their immediate community was a classic Social Gospel refrain, inasmuch as it sought to persuade its audience to take social moral obligations seriously. He later came to the conclusion that the hyperindividualism for which he called out his own people was quintessentially an American trait. In retrospect, therefore, the scope of his argument had been too narrow: he accused his own ethnic enclave of a tendency that ran deep in American society more broadly. Although Niebuhr hadn’t yet mastered the large-scale thinking that would come to characterize his later thought, in the Atlantic piece we observe him “learning to use this big picture of the history of Chris...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Table of Contents

- Foreword by Robin W. Lovin

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: An American Conscience

- 1. The Preacher-Activist

- 2. Hope amid Chaos

- 3. Visions of a New World Order

- 4. Bumbling Knights and Nuclear Warheads

- 5. Niebuhr and the Twenty-First-Century Conscience

- Bibliography

- Contributors

- Index