eBook - ePub

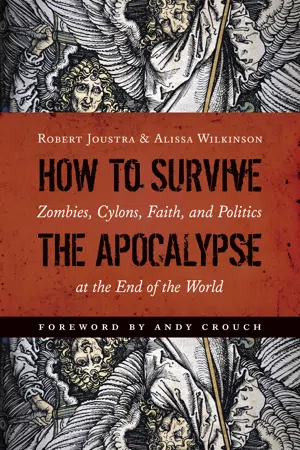

How to Survive the Apocalypse

Zombies, Cylons, Faith, and Politics at the End of the World

- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

How to Survive the Apocalypse

Zombies, Cylons, Faith, and Politics at the End of the World

About this book

Incisive insights into contemporary pop culture and its apocalyptic bent

The world is going to hell. So begins this book, pointing to the prevalence of apocalypse — cataclysmic destruction and nightmarish end-of-the-world scenarios — in contemporary entertainment.

In How to Survive the Apocalypse Robert Joustra and Alissa Wilkinson examine a number of popular stories — from the Cylons in Battlestar Galactica to the purging of innocence in Game of Thrones to the hordes of zombies in The Walking Dead — and argue that such apocalyptic stories reveal a lot about us here and now, about how we conceive of our life together, including some of our deepest tensions and anxieties.

Besides analyzing the dsytopian shift in popular culture, Joustra and Wilkinson also suggest how Christians can live faithfully and with integrity in such a cultural context.

The world is going to hell. So begins this book, pointing to the prevalence of apocalypse — cataclysmic destruction and nightmarish end-of-the-world scenarios — in contemporary entertainment.

In How to Survive the Apocalypse Robert Joustra and Alissa Wilkinson examine a number of popular stories — from the Cylons in Battlestar Galactica to the purging of innocence in Game of Thrones to the hordes of zombies in The Walking Dead — and argue that such apocalyptic stories reveal a lot about us here and now, about how we conceive of our life together, including some of our deepest tensions and anxieties.

Besides analyzing the dsytopian shift in popular culture, Joustra and Wilkinson also suggest how Christians can live faithfully and with integrity in such a cultural context.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access How to Survive the Apocalypse by Robert Joustra,Alissa Wilkinson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Popular Culture in Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

The World Is Going to Hell

Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.

J. Robert Oppenheimer, quoting the Bhagavad Gita

In order to engage effectively in this many-faceted debate, one has to see what is great in the culture of modernity, as well as what is shallow and dangerous.

Charles Taylor, The Malaise of Modernity

The world is going to hell.

Just turn on the television — no, not the news. Flip over to the prestige dramas and sci-fi epics and political dramas. Look at how we entertain ourselves. Undead hordes are stalking and devouring, alien invasions are crippling and enslaving, politicians ignore governance in favor of sex and power, and sentient robots wreak terrible revenge upon us.

Today, apocalypse sells like mad. Not just the threat of it, but its reality. And especially its aftermath.

This is objectively weird when you think about it. So we go to work all day and then come home, reheat some pizza, flop down on the couch . . . and watch our own destruction for fun? What’s going on here? Why would we do such a thing?

One easy answer — too easy — is that our fixation on the end of the world (and us) is itself a sort of sign of the end of civilization. As the narrative goes, we’re a bunch of lazy, privileged Westerners with no real wars to fight, no real struggles, and we have to watch this stuff to get our adrenaline fix. Only people with the luxury of comfort and relative stability could afford to entertain themselves with their own destruction, right?

Well. Yes and no. As long as we humans have been telling the story of our beginning, we’ve also been telling the story of our end — for every Asgard and Midgard, a Ragnarok; for every Garden of Eden, an Armageddon. These stories of “apocalypse” are about the end of the world and the destruction of civilization. This is how it all ends.

But apocalyptic literature is not really just about the end of the world.

The Greek word apokalypsis means not only destruction, not only the disruption of reality, but the dismantling of perceived realities — an ending of endings, a shocking tremor of revelation that remade creation in its wake. It renews as it destroys; with its destruction it brings an epiphany about the universe, the gods, or God.

Apocalyptic literature has always said a great deal more about who we are now — the makers and the receivers — than who we might be in the future. It reveals more than predicts. And that’s why our stories have changed over time: when the way we think about ourselves as individuals and societies changes, our apocalypses change too.

In other words, there’s more to our obsessions with zombies and Cylons and robots and presidents behaving badly than meets the eye.

It’s All Our Fault

Our forefathers conceived of Ragnarok or Armageddon as a judgment visited from on high upon mankind, a Day of Reckoning chosen and enacted by a God or gods. But today, we imagine the apocalypse differently: we’ve swapped ourselves into the position of apocalypse-enactor.

We have science, and scholarship, and technology, all of which let us understand and manipulate our environment with previously unthinkable powers: we can cure disease, beam a message around the globe in seconds, walk on the moon, see the invisible. Our destinies are in our hands, and that control is so broad, so unprecedented, that apocalypse is within our grasp.

You and I have become gods. But that has come with a price: now we can bring about the end. We are the authors of our own destruction.

Since the early Cold War, the doctrine of mutually assured destruction — launch the missile, we’ll launch one back — has constantly reminded us that we teeter on the edge.1 One diplomatic misstep or inadvertent bump of the button, and our thin veneer of civilization will crack. Our godlike powers are as much a product of our power to destroy as to create.

Our novels and stories and movies and TV shows have shifted from a dominantly utopian imagination to one marked by the apocalyptic — and the dystopian. We once had the Cold War utopianism of Captain Kirk; now we have J. J. Abrams’ Star Trek into Darkness, with its none-too-metaphorical annihilation of logic — an inversion of the Trek universe — through the destruction of the planet Vulcan. We’ve gone from the idealist psycho-history of Isaac Asimov to the fatalist siren call of the Cylons in Battlestar Galactica. We went from the sacrificial valor of Hobbits to the purging of innocence in Westeros.

What happened? What scorched our fantasy landscape? Why this extraordinary dystopian shift in popular imagination?

An answer lurks in something the philosopher Charles Taylor calls the “malaise of modernity,” by which he means the things we obsess about and the tensions endemic to our modern moral order — an order Taylor calls “secular” (though he means something different by that than you might expect). Our dystopias are different from the apocalypses we saw in the past — in the history of the Christians, Jews, Hindus, and others — because they take a secular form.

Exploring this is useful and interesting, but in this book we don’t just intend to perform some thoughtful cultural analysis, as valuable as that may be. Our project is bigger: we want to peer through the lens of apocalypse at ourselves, looking at these dystopias to see how we conceive of our life together — our politics. Then, having seen ourselves more clearly, we want to offer a few modest proposals for getting from dystopia back to apocalypse. We want to see what is good and what is broken in our culture, so we can then have more meaningful discussions about how to maximize one and heal the other.

What We Talk about When We Talk about “Secular”

When we say that today’s dystopias are different because they are “secular,” we mean something different from what most people mean when they use the word today, something quite complex and nuanced.2

We frequently talk about “secularity” as a kind of marginalization or eclipse of the religious — religion being blocked out or removed from particular societal spheres. But that isn’t sufficient for really understanding our times. To say we are “secular,” Taylor says, is to say that all of us think differently and live differently than we did in the past. We haven’t just eliminated or emasculated God or the gods; we’ve also gotten rid of traditions, times, places, and anything that tries to resist or claim itself higher than the immanent will of the person. And even those of us who still believe in these things live in a world marked by the ability to choose not to believe in them; I can plausibly convert to, or de-convert from, most any belief system, regardless of my heritage or ethnicity.

This is quite a change. It required an anthropocentric shift: a turn toward putting the human person at the center of the universe as the creator of meaning. No longer do we find our reasons for existence out in the cosmos or in some metaphysical dimension. Instead, humans have radical power to make and decide their own meaning.

Ironically, of course, though we live in a universe where we are in charge, all we see on the horizon is our end. This is dystopia. We have the power to make our own futures that the Enlightenment promised, but it isn’t all it’s cracked up to be — we were promised parachutes, and what we got were knapsacks.

You might be tempted to think this is all bad. Shouldn’t we decry this shift as some kind of self-devolution?

But hold your fire for now. Taylor, at least, isn’t going to characterize this as either a good or a bad thing. With ...

Table of contents

- Contents

- Foreword

- 1. The World Is Going to Hell

- 2. A Short History of the Secular Age

- 3. A Short History of the Apocalypse

- 4. Keep Calm and Fight the Cylons: New Ways to Be Human

- 5. Remember My Name: Antiheroes and Inescapable Horizons

- 6. A Lonely Man, His Computer, and the Politics of Recognition

- 7. Winter Is Coming: The Slide to Subjectivism

- 8. How to Survive the Zombie Apocalypse

- 9. The Scandal of Subtler Languages

- 10. May the Odds Be Ever in Your Favor: Learning to Love Faithful Institutions

- 11. On Babylon’s Side

- Acknowledgments