- 215 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

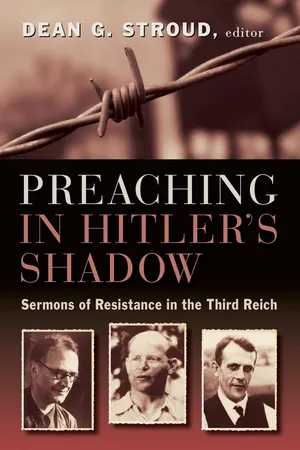

About this book

What did German preachers opposed to Hitler say in their Sunday sermons? When the truth of Christ could cost a pastor his life, what words encouraged and challenged him and his congregation? This book answers those questions.

Preaching in Hitler's Shadow begins with a fascinating look at Christian life inside the Third Reich, giving readers a real sense of the danger that pastors faced every time they went into the pulpit. Dean Stroud pays special attention to the role that language played in the battle over the German soul, pointing out the use of Christian language in opposition to Nazi rhetoric.

The second part of the book presents thirteen well-translated sermons by various select preachers, including Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Karl Barth, Rudolf Bultmann, and others not as well known but no less courageous. A running commentary offers cultural and historical insights, and each sermon is preceded by a short biography of the preacher.

Preaching in Hitler's Shadow begins with a fascinating look at Christian life inside the Third Reich, giving readers a real sense of the danger that pastors faced every time they went into the pulpit. Dean Stroud pays special attention to the role that language played in the battle over the German soul, pointing out the use of Christian language in opposition to Nazi rhetoric.

The second part of the book presents thirteen well-translated sermons by various select preachers, including Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Karl Barth, Rudolf Bultmann, and others not as well known but no less courageous. A running commentary offers cultural and historical insights, and each sermon is preceded by a short biography of the preacher.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Preaching in Hitler's Shadow by Dean G. Stroud in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & German History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

SELECTED SERMONS OF RESISTANCE IN THE THIRD REICH

Proclaim the message; be persistent whether the time is favourable or unfavourable; convince, rebuke, and encourage, with the utmost patience in teaching.

2 TIMOTHY 4:2 NRSV, CATHOLIC EDITION

Except for the Bonhoeffer sermon, the sermon translations are by the editor.

DIETRICH BONHOEFFER

.......................................................................................................

Gideon

Born in Breslau in 1906, the twins Dietrich and Sabine were among the eight children of Karl and Paula Bonhoeffer. The father was a professor of psychiatry in Berlin where the family lived in a large home in an upper-class section of the capital. For Dietrich, his family was the center of his life.1 But the First World War shattered the idyllic environment of the Bonhoeffers when Walter, one of the children, was killed in battle.2

As a student, Dietrich was simply brilliant. He finished his doctoral studies at the age of twenty-one and his dissertation, Sanctorum Communio, continues to be read and discussed. During the academic year 1930-31 he studied at Union Theological Seminary in New York, where he came into contact with the African American community of Harlem. He attended worship services and was moved by the vitality of the spirituals. But contact with a community of citizens suffering discrimination sensitized him even more to the sufferings of German Jews under Hitler. At Union the German theologian became friends with the French pacifist Jean Lasserre, who helped him to see the “absurdity of Christians killing people for the sake of national pride or territorial ambitions.”3 Furthermore, it was his new French acquaintance who helped Bonhoeffer understand that Jesus’ radical insistence that his followers practice peace (love of the enemy, nonresistance, going the second mile, etc.) was meant not for the first century alone but for all Christians in all times until the end of time.4 At the time, these ideas pointed Bonhoeffer toward Gandhi, and soon he had plans to travel to India to study, but the trip never took place because he was called back to Germany to aid the Confessing Church in the training of seminary students.

Confessing Church seminarians were forbidden to attend German universities, and members of the Confessing Church were not allowed to teach at universities either. Therefore the Confessing Church established an underground seminary in the secluded village of Finkenwalde near the Baltic Sea. In his lectures at Finkenwalde, Bonhoeffer offered future pastors in the Confessing Church a startling interpretation of Jesus’ call to radical discipleship. Here too the seeds planted in America by his French friend bore fruit in German soil. Bonhoeffer would later revise and publish his lectures under the title Nachfolge (discipleship).

The police closed the seminary at Finkenwalde in September 1937. Soon thereafter some twenty-seven of his Finkenwalde students were in Nazi jail cells. In January 1938 the Nazis forbade Bonhoeffer’s presence in Berlin, and it was only with special permission that he was permitted to visit his parents.5 As life became more and more difficult in Germany, Bonhoeffer accepted an invitation to teach in the United States, but soon after his arrival he decided to return to Germany. Bonhoeffer left New York for Germany on July 27, 1939.

A little more than a year later, in September 1940, Bonhoeffer, like so many other pastors, was officially banned from preaching and speaking in the Third Reich.6 Soon thereafter he joined a small group of conspirators whose chief goal was to murder Adolf Hitler and negotiate an end to the war, primarily with England. As part of this activity, the group was able to rescue a few Jews from the Nazi terror.7

Bonhoeffer’s work with the Abwehr allowed him and others in his circle to have firsthand knowledge of the severity of Hitler’s policy against Jews.8 Certainly this information only increased his sense of obligation for personal sacrifice for this oppressed minority. His willingness to join what became the July 20 plot was foreshadowed by his essay “The Church and the Jewish Question,” which he wrote in the early days of the Church Struggle (see the editor’s introduction). He had been greatly disappointed by the timidity of the Confessing Church in the face of Nazi persecution of the Jews.9 At the time of the Barmen Confession, Bonhoeffer was serving as pastor to a German-speaking church in London. Although absent, he followed the developments of the Confessing Church closely, and the Barmen Confession pleased him in its radical affirmation of the unique Lordship of Christ in the church, but its silence in the face of Nazi persecution of the Jews greatly disappointed him.10

This increasing violence against Jews certainly influenced his shift in thinking from pacifism to violent resistance.

After his arrest in April 1943, Bonhoeffer continued to be a model of Christian courage. The prison offered new opportunities to practice obedience to Christ in the midst of great suffering, danger, and even torture. His writings from prison, published as Letters and Papers from Prison, have equaled his book on discipleship in popularity. Like Paul Schneider in Buchenwald (see below), Dietrich Bonhoeffer refused to allow prison confinement to silence Christian witness.

By special orders of Hitler, Bonhoeffer was hanged on April 9, 1945, just days before Germany surrendered.

The sermon in this collection comes from the early days of the Third Reich. As early as 1933 it had become obvious to Bonhoeffer that the new Reich was evil. Hatred of Jews and preparation for war were daily fare for Germans. When Bonhoeffer preached his first sermon following Hitler’s coming to power, he surely must have known that Jewish Gideon would present a sharp contrast to German rhetoric against Jews and for war. His repeated emphasis on Gideon’s lack of military forces in the face of greater military strength must have made an impression on the congregation. Also, the talk of altars reflected the altars in German churches that had been profaned with Nazi flags and pictures of Hitler. The sermon on Gideon offered Germans in the new Reich a radical choice between the Judeo-Christian God of tradition and Germanic paganism.

Gideon[1]

February 26, 1933[2]

Berlin, Germany

Berlin, Germany

And he said unto him, Oh my Lord, wherewith shall I save Israel? behold, my family is poor in Manasseh, and I am the least in my father’s house. And the LORD said unto him, Surely I will be with thee, and thou shalt smite the Midianites as one man. . . . And the LORD said unto Gideon, The people that are with thee are too many for me to give the Midianites into their hands, lest Israel vaunt themselves against me, saying, Mine own hand hath saved me. . . . And Gideon said unto them, I will not rule over you, neither shall my son rule over you: the LORD shall rule over you.

Judges 6:15-16; 7:2; 8:23 KJV [3]

This is a passionate story about God’s derision[4] for all those who are fearful and have little faith, all those who are much too careful, the worriers, all those who want to be somebody in the eyes of God but are not. It is a story of God’s mocking human might, a story of doubt and of faith in this God who makes fun of human beings, who wins them over with this mockery and with love. So it is no rousing heroic legend — there is nothing of Siegfried[5] in Gideon. Instead it is a rough, tough, not very uplifting story, in which we are all being roundly ridiculed along with him. And who wants to be ridiculed, who can think of anything more humiliating than being made a laughingstock by the Lord of the world? The Bible often speaks of God in heaven making fun of our human hustle and bustle, of God’s laughter at the vain creatures he has made. Here it is the powerful Sovereign One whose strength is unequaled, the living Lord, who carries on this way about his creatures. For him, who has all power in his hands, who speaks a word and it is done, who breathes forth his spirit and the world lives, or takes it away and the world perishes, who dashes entire nations[6] to pieces, like potters’ vessels for this God, human beings are not heroes, not heroic, but rather creatures who are meant to do his will and obey him, whom he forces with mockery and with love to be his servants.

So that’s why we have Gideon and not Siegfried, because this doubter, mocked by God, has learned his faith in the school of hard knocks.

In the church we have only one altar — the altar of the Most High, the One and only, the Almighty, the Lord, to whom alone be honor and praise, the Creator before whom all creation bows down, before whom even the most powerful are but dust. We don’t have any side altars at which to worship human beings. The worship of God and not of humankind is what takes place at the altar of our church. Anyone who wants to do otherwise should stay away and cannot come with us into God’s house.[7] Anyone who wants to build an altar to himself or to any other human is mocking God, and God will not allow such mockery. To be in the church means to have the courage to be alone with God as Lord, to worship God and not any human person. And it does take courage.[8] The thing that most hinders us from letting God be Lord, that is, from believing in God, is our cowardice. That is why we have Gideon, because he comes with us to the one altar of the Most High, the Almighty, and falls on his knees to this God alone.

In the church we also have only one pulpit, from which faith in God is preached and not any other faith, not even with the best intentions. This again is why we have Gideon — because he himself, his life story is a living sermon about this faith. We have Gideon because we don’t want always to be speaking of our faith in abstract, otherworldly, irreal, or general terms, to which people may be glad to listen but don’t really take note of; because it is good once in a while actually to see faith in action, not just hear what it should be like, but see how it just happens in the midst of someone’s life, in the story of a human being. Only here does faith become, for everyone, not just a children’s game, but rather something highly dangerous, even terrifying.[9] Here a person is being treated without considerations or conditions or allowances; he has to bow to what is being asked, or he will be broken. This is why the image of a person of faith is so often that of someone who is not beautiful in human terms, not a harmonious picture, but rather that of someone who has been torn to shreds. The picture of someone who has learned to have faith has the peculiar quality of always pointing away from the person’s own self, toward the One in whose power, in whose captivity and bondage he or she is. So we have Gideon, because his story is a story of God glorified, of the human being humbled.

Here is Gideon, one person no different from a thousand others, but out of that thousand, he is the one whom God comes to meet, who is called into God’s service, is called to act. Why is he the one, or why is it you, or I? Is it because God wants to make fun of me, in coming to talk with me? Is it God’s grace, which makes a mockery of all our understanding? But what are we asking here? Isn’t God entitled to call whomever God chooses, you or me, the highly placed or the lowly, strong or powerless, poor or rich, without our being entitled to start arguing about it straightaway? Is there anything we can do here other than hear...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Editor’s Introduction

- Selected Sermons of Resistance In the Third Reich

- Appendix: A Sermon About the Loyalty Oath to Adolf Hitler

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Permissions