![]()

Chapter 1 - History of Rockets

It was in the early thirteenth century that man turned toy fireworks into weapons of war. The first recorded use of rockets as military weapons was in defense of Kai Fung Fu, China, in 1232.

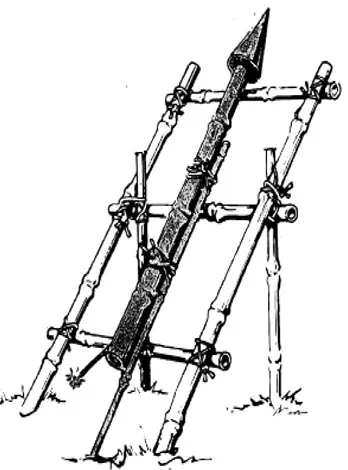

Fig 1-1. The Chinese “arrows of flying fire”

The Chinese “arrows of flying fire” were fired from some sort of crude rack-type launcher- and were propelled by gunpowder. The gunpowder was packed in a tube (probably bamboo) that had a hole in one end for the escaping hot gases, a closed end for the push to be exerted against, and a long stick as an elementary guidance system.

About 1280 A.D., Arab military men, referring to the propulsive ability of gunpowder, suggested improvements over the simple Chinese skyrocket. One interesting innovation was what might be best described as an air squid or traveling land mine; it could scurry across land in the manner of a squid through water.

It was about 1400 when rocketry became of commercial importance throughout Europe and especially in Italy—where perhaps the greatest designers of pyrotechnics were found. The use of fireworks for all sorts of celebrations created a major market for the manufacture of large quantities of rockets. This spread throughout Europe and reached its zenith during the middle of the eighteenth century.

One of the earliest technical publications on rocketry, the Treatise Upon Several Kinds of War-Fireworks, appeared in France in 1561. The treatise made a critical analysis of the rockets used in earlier military campaigns. A recommendation was made to substitute varnished leather cases for the commonly accepted paper and bamboo ones. There is no evidence that this suggestion was followed by later rocketeers.

Comparatively, refinements in rocket design came faster in the next few hundred years, at least on paper. In 1591, some three hundred years before Dr. Robert Goddard thought of it, a Belgian, Jean Beavie, described and sketched the important idea of multi-staged rockets. Multi-staging, placing two or more rockets in line and firing them in step fashion, is today’s practical answer to the problem of escaping earth’s gravitational attraction.

By 1600, rockets were being used in various parts of Europe against cavalry, foreshadowing the modern antitank hand weapon, and the bazooka of World War II and Korean fame. Later, in 1630, a paper was written describing exploding aerial rockets which created an effect similar to that of the twentieth- century shrapnel shell. By 1688, rockets weighing over 120 pounds had been built and fired with success in Germany. These German rockets, carrying 16-pound warheads, used wooden powder cases reinforced with linen.

Toward the end of the eighteenth century, a London lawyer, Sir Walter Congreve, became fascinated by the challenge to improve rockets. He made extensive experimentation on propellants and case design. His systematic approach to the problem resulted in improved range, guidance, and incendiary capabilities. The British armed forces used Congreve’s new rockets to great advantage during the Napoleonic Wars.

When Congreve died in 1828, his applied engineering and dedication had already resulted in several technological advances. In addition to fortified cases, new propellants, and incendiaries, Congreve developed stabilizing fins that provided rocketeers with effective guided missiles.

The latter half of the nineteenth century saw the demise of rockets as weapons, but man’s ingenuity, fortified with rapidly expanding technology, was directed towards the challenge of human transportation by rockets. This period of time and the first quarter of the twentieth century saw the significant growth of reasoning and mathematics applied to rocket development. For the most part, military applications were forgotten. The founders of modern rocketry made their appearance at the threshold of the exciting events of our time.

A Russian assassin, Nikolai Kibaltchitch, while in prison awaiting trial in 1881, proposed a rocket ship powered by controlled firing of explosive pellets. His ship consisted of a firing chamber centered above a hole in a manned platform. The firing chamber could be rotated 90 degrees to move the ship in a horizontal direction. To avoid any influence of public opinion in favor of the prisoner, Russian officials withheld his plans. It wasn’t until after the Russian Revolution that Kibaltchitch’s writings were finally revealed.

In 1891, a German inventor, Hermann Ganswindt, designed a spaceship for travel to Mars. He also described a propulsion system similar to that of Kibaltchitch, except that he suggested a series of dynamite explosions that would shoot out steel balls with the hot exhaust. He reasoned that controlled explosions would eventually allow the ship to escape the earth’s gravitational attraction. Ganswindt also proposed the idea of rotating the ship while in space to produce an artificial gravity for the passengers, thereby recognizing the weightlessness phenomenon. He never succeeded in obtaining support for his impractical propulsion scheme.

Tsiolkovsky—

Father Of Interplanetary Travel

The first person to spell out the theory of space travel as based on serious mathematical study was a deaf and poor Russian school teacher. For many years he was barely noticed in his own country and drew even less attention elsewhere. Now recognized as the father of astronautical theory and of Russian rocketry, Konstantin Tsiolkovsky was one of the first, if not the first, to suggest the use of liquid propellants. For centuries, solids like gunpowder were considered to be the only possible fuels. There was, however, a Peruvian, Pedro Paulet, who claimed in 1925 that he had built and successfully fired in 1895 a 5-pound rocket engine which used gasoline and nitrogen peroxide. It is doubtful that this event took place, at least as early as clai...