- 342 pages

- English

- PDF

- Available on iOS & Android

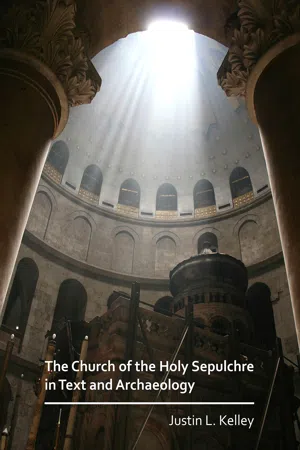

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Text and Archaeology

About this book

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Jerusalem, was built by the Byzantine emperor Constantine I to commemorate the Passion of Jesus Christ. Encased within its walls are the archaeological remains of a small piece of ancient Jerusalem ranging in date from the 8th century BC through the 16th century AD, at which time the Turkish Ottoman Empire ushered Jerusalem into the modern period. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre was the subject of extensive archaeological investigation between 1960 and 1981 during its restoration. With the development of non-destructive techniques of archaeological research, investigation within the church has continued, which led to the restoration and conservation of the shrine built over the Tomb of Jesus in 2017. The first part of this monograph focuses on the archaeological record of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, surveying past excavations as well as recent research carried out within the church over the past three decades. The archaeological survey provides historical context for the second part of the book—a collection of primary sources pertinent to the history of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. The texts included here range in date from the 1st century AD to the mid-19th century and are presented in their original languages with English translation.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Table of contents

- Copyright Information

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- Abbreviations

- List of Figures and Tables

- Preface

- Introduction

- Archaeological periodization of Palestine: Iron Age II – Ottoman period

- The history of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre: a structural, archaeological and textual timeline

- A brief history of Jerusalem from 30/33 AD to 1830 with emphasis on the Church of the Holy Sepulchre

- Chapter 1

- Figure 1.1. General layout of the city of Jerusalem through its phases of development. The lighter gray fortification line is he 16th century Turkish wall that also makes up the present wall of the Old City. 1) Jerusalem in the 1st century AD before the

- Chapter 2

- The Church of the Holy Sepulchre: A history of research

- Figure 2.1. Plan of the present form of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre highlighting the extant archaeological remains (shaded areas; black = 4th century, dark gray = 11th century, light gray = 12th century) and reconstruction of the Constantinian edific

- Archaeological investigation inside the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and its vicinity

- Figure 3.1. Plan of the present-day Church of the Holy Sepulchre complex: 1) the parvis (courtyard), 2) main entrance, 3) Greek Katholikon, 4) north transept, 5) Byzantine gallery, 6) apse of the Katholikon, 7) ambulatory, 8) Chapel of Longinus, 9) Chapel

- Figure 3.2. The Holy Sepulchre complex and surrounding structures: 1) the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, 2) the Lutheran Church of the Redeemer, 3) the Muristan complex, 4) the Church of St. John Prodromos (source: J. Kelley, based on Salmon 2006).

- Figure 3.3. Bedrock at the bottom of Ute Lux’s archaeological probe in the Church of the Redeemer (source: T. Powers).

- Figure 3.4. Plan of the excavations in the Chapel of St. Vartan. The numbering system used here is that of Gibson and Taylor (1994: Fig. 6): Walls 1–3 and 7 date to the 2nd century AD, Walls 4 and 6 date to the 4th century AD, Walls 5 and 8 date to the 11

- Figure 3.5. The ceiling and northern wall (looking northwest) of the artificial cave outside the Chapel of St. Vartan. Clear races of quarrying are evident on the upper portion of the wall and the floor (source: J. Kelley).

- Figure 3.6. The ceiling and southern wall (looking northeast) of the artificial cave in the Chapel of the Invention of the Cross (source: J. Kelley).

- Figure 3.7. Late Roman Period wall in the Chapel of St. Vartan (Wall 7) looking northeast (source: J. Kelley).

- Figure 3.8. Wall 1, looking southeast. The drawing of the ‘Jerusalem Ship,’ now in a picture frame, can be seen on the east co ner of the wall (source: J. Kelley).

- Figure 3.9. Plan of the Constantinian church (source: Gibson and Taylor 1994: Fig. 45).

- Figure 3.10. Photograph of the ‘Jerusalem Ship’ as it appears at the present. The photograph is taken looking south so that the ship is oriented with its bow (front) to the east and its stern (rear) to the west (source: J. Kelley).

- Figure 3.11. Drawing of the ‘Jerusalem Ship’ and inscription. Gray lines indicate sections of the drawing that were executed i red ink. The principal parts of the ship include: 1) foresail (artemon) mast; 2) lower wale; 3) upper wale; 4) goose-head orna

- Figure 3.12. Drawing of a ship relief on the Naevoleia Tyche tomb monument in Pompeii. The relief dates to c .79 AD and is a good parallel to the ‘Jerusalem Ship’ (source: Clarke 1836: 269; see also Casson 1971: Fig. 151; Gibson and Taylor 1994: 42).

- Chapter 4

- The Church of the Holy Sepulchre in the archaeological and literary annals of Jerusalem

- Figure 4.1. (pages 68–69) Reconstruction of the ancient quarry by Gibson and Taylor showing caves and rock-cut tombs in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and the immediate vicinity: 1) quarrying below the northern transept 46 (Corbo 1981–1982: Pl. 10, Phot

- Figure 4.2. Reconstruction of the known areas of the ancient quarry based on the excavations and soundings carried out in the church in the 1960s–80s: 1) the Holy Sepulchre, 2) Chapel of the Angel, 28) rock-cut tomb, traditionally ascribed to Joseph of Ar

- Figure 4.3. Sketch showing how Golgotha might have looked in the 1st century AD based on the reconstruction of the ancient qua ry by Gibson and Taylor (1994: Fig. 36): 1) the Tomb of Jesus (cf. Fig. 4.1:21); 2) the Tomb of Joseph of Arimathea (cf. Fig. 4.

- Figure 4.4. An ossuary from 1st century Jerusalem, now on display in the Israel Museum, Jerusalem (source: J. Kelley).

- Figure 4.5. Typical burial cave of the 1st century AD (source: J. Kelley).

- Figure 4.6. Reconstruction of the tomb of Jesus by Vincent (source: Vincent and Abel 1914: 96, Fig. 53).

- Figure 4.7. Drawing of the Narbonne model of Constantine’s Edicule. This sculpture probably dates to the 5th century AD and is one of the best representations of the original Edicule (source: J. Kelley; see also Wilkinson 1981: 250 and Biddle 1999: Figs.

- Figure 4.8. Reconstruction of the rock-cut tomb of Jesus (source: J. Kelley).

- Figure 4.9. Digital plan of the Edicule based on scans taken with ground penetrating radar by the National Technical University of Athens. The Crusader period Edicule is also indicated on the plan as a superimposed outline (source: Agrafiotis et al. 201:

- Figure 4.10. The remains of the rock-cut tomb as they appeared in the digital reconstruction of the Edicule by the National Technical University of Athens (source: Agrafiotis et al. 2017: Fig. 9).

- Figure 4.11. Sketch of the findings of the NTUA and their placement within the Edicule (source: J. Kelley; see also Agrafiotis et al. 2017: Fig. 10).

- Figure 4.12. Late Roman architectural remains in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre: 1) the Holy Sepulchre, 2) the Rock of Golgotha, 3) wall foundation northeast of the Edicule (Corbo 1981–1982: Pl. 19.1); 4) wall G-G in northern transept 46 (Corbo 198–198

- Figure 4.13. Chamber 68 from the excavations in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (source: Corbo 1981–1982: Photo 51, courtesy of the Studium Biblicum Franciscanum, Jerusalem).

- Figure 4.14. Drawing of the reverse sides of two Aelia Capitolina coins dating to the reign of Antoninus Pius, the successor o Hadrian. The coins depict Tyche in her temple—the left coin with a hexastylos façade and the right with a tetrastylos. The insc

- Figure 4.15. Plan of the Hadrianic Temple built over the site of the old quarry (source: Corbo 1981–1982: Pl. 68, courtesy of the Studium Biblicum Franciscanum, Jerusalem).

- Figure 4.16. Figure 4.16. Plan of the Constantinian church: 1) Tomb of Jesus/Edicule; 2) the Rotunda (Anastasis); 3) western open-air courtyard; 4) Rock of Golgotha; 5) Basilica (martyrium); 6) open-air courtyard; 7) entrance to the complex (propylaea); 8

- Figure 4.17. The Madaba mosaic map depicting Palestine in the mid-sixth century AD Jerusalem (shown here) is at the center of the map and is shown larger than the other cities. The inscription to the upper left (northeast) of the city (not shown) reads Ha

- Figure 4.18. The Byzantine Church of the Holy Sepulchre as it appears in the fifth century Madaba Map: 1) Constantine’s Basilica; 2) the Baptistery complex; 3) Monastery of the Spoudaei; 4) Palace of the Patriarch; 5) Clergy House connected with the Patri

- Figure 4.19. Two pewter pilgrim flasks in the Treasury of the Monza Cathedral and Bobbio Abbey in Milan, Italy. These flasks were made in the late sixth/early 7th century AD, probably in Palestine. They feature the façade of the Constantinian Edicule (sou

- Figure 4.20. A eulogia token from the fourth century AD with an image of the Constantinian Edicule on the front. The piece is ow on display at the Israel Museum, Jerusalem (source: M. Kelley).

- Figure 4.21. Excavations in the Katholikon of the of the present-day church that revealed remains of the Constantinian Triportico and Basilica: A) eastern stylobate of the Constantinian Triportico, B) apse of the Basilica, C) apse of the 12th century Chor

- Figure 4.22. Ground plan of the Chapel of Golgotha and the excavations of Katsimbinis east of the Rock of Golgotha (source: Corbo 1981–1982: Pl. 40, courtesy of the Studium Biblicum Franciscanum, Jerusalem; cf. Katsimbinis 1977: Pls. A–B).

- Figure 4.23. Section of the excavations behind the Rock of Golgotha (looking south) (source Corbo 1981–1982: Pl. 41, courtesy of the Studium Biblicum Franciscanum, Jerusalem; cf. also Katsimbinis 1977: Pl. C).

- Figure 4.24. Small cave cut in the eastern flank of the Rock of Golgotha (source: Corbo 1981–1982: Photo 93, courtesy of the Studium Biblicum Franciscanum, Jerusalem).

- Figure 4.25. Plan of the 11th century church following the repairs of 1020–1048 (source: Corbo 1981–1982: Pl. 4, courtesy of the Studium Biblicum Franciscanum, Jerusalem).

- Figure 4.26. Plan of the Crusader church (source: Corbo 1981–1982: Pl. 6, courtesy of the Studium Biblicum Franciscanum, Jerusalem).

- Figure 4.27. The domes and terraces of the present-day Church of the Holy Sepulchre highlight the form of the church established by the Crusaders (source: Corbo 1981–1982: Pl. 56, courtesy of the Studium Biblicum Franciscanum, Jerusalem).

- Part II Historical Sources for the Study of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre

- Chapter 5

- Contextual notes on the historical sources

- Selected excerpts from the historical sources: Golgotha and the Tomb of Jesus to the destruction of the Constantinian Basilica (30/33–1009 AD)

- Figure 6.1. Syriac text of Theophania 3.61 (source: Lee 1842: 96).

- Figure 6.2. Syriac text of Theophania 4.20 (Lee 1842: 58).

- Figure 6.3. Arculf’s sketch of the layout of Constantine’s church (source: CSEL 39: 231; see also Meehan 1958: 46–47 and Wilkinson 1977: Pl. 5–6; Biddle 1999: 27, Fig. 25).

- Chapter 7

- Selected excerpts from the historical sources: The reconstruction of the Church to its final major restoration (1048–1831 AD)

- Figure 7.1. Dedicatory inscription as recorded by Francesco Quaresmius in 1639 (source: Quaresmius 1639: 483).

- Figure 7.2. Arabic text of Yakut al-Hamawi’s description of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (source: Wüstenfeld 1869: 173–174).

- Chapter 8

- Selected excerpts from the historical sources: Legendary accounts of the founding of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre

- Figure 8.1. Traditional location of the discovery of the ‘true cross’ in the southeastern corner of the Chapel of the Inventio of the Cross (source: Corbo 1981–1982: Photo 111, courtesy of the Studium Biblicum Franciscanum, Jerusalem).

- Appendix 1

- Supplementary historical sources for the study of Jerusalem and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre

- Additional Consulted Works