eBook - ePub

Coming of Age in South and Southeast Asia

Youth, Courtship and Sexuality

- 307 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Coming of Age in South and Southeast Asia

Youth, Courtship and Sexuality

About this book

In recent years, first feminist considerations, and now concerns with HIV/Aids have led to new approaches to the study of sexuality. The experience of puberty, explorations with sexuality and courtship, and the pressure to reproduce are a few of the human tensions central to this volume.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Coming of Age in South and Southeast Asia by Lenore Manderson,Pranee Liamputtong Rice in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Regional Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Water Serpents and Staying by the Fire: Markers of Maturity in a Northeast Thai Village

INTRODUCTION

The transition from childhood to adulthood is not a purely biological process, but a movement through socially constructed categories of age. Many societies mark the social shift from child to adult through rituals and ceremonies. This chapter describes two rites of passage for young people in a remote, rural village in Northeast Thailand: ordination as a monk for young men and childbirth and postpartum rituals for young women. In the Northeast, these rites mark the transitions between socially defined immaturity and social adult maturity. The subject of the rites acquires from the symbolic and subjective experience of these rituals a changed sense of self as a sexually mature, socially recognized adult male or female. The meanings involved in these rites are multivalent, but this chapter will concentrate upon their significance to understanding constructs of gender.

Writings on Thailand concur on the significance of the ordination in the formation of a young mans social status (Keyes 1984, 1986; Kirsch 1985; Tambiah 1970). In contrast, there is little written about mothers’ postpartum activities as ritual practices of importance to women. Unlike the public, elaborate ordination rites, the practices of birth and postpartum as a means of marking women’s maturity do not involve obvious public acknowledgement. For this reason they have remained described as ethnographic medical exotica concentrating on the status of the new baby, rather than analysed in terms of their significance to women as markers of maturity.

This chapter considers the links between discourses of maturity and embodied potency in village society. These rites enact the appropriate concentration and enculturation of female and male potency towards the regeneration and nurturing of village society. The analysis within this chapter builds upon previous views of gender in Thailand (Ford and Sirinan 1993; Keyes 1984, 1986; Kirsch 1985; Mills 1995). However, here I explore the relationships of men and women to society not as structural oppositions but in terms of discursive practices which position men and women’s power in different ways depending upon the context. Despite rapid social change that promotes many newer forms of feminine and masculine identity through labour migration, small families, education and material success, these rites continue to have social significance in Ban Srisaket. They remain not as static traditions but as practices retaining important meanings for villagers at the same time as they are adapted to the changed lifestyles of men and women.

BAN SRISAKET

The Northeast region of Thailand (known as Isan) is the least developed and poorest region of Thailand. The majority of the population are ethnically distinct, Lao-speaking people who express a collective identity based upon domestic language, cultural practices and regional history distinct from central Thai people. The remote rural village of Ban Srisaket is located in the heartland of central Isan in Roi Et province.1 It is the largest community in its sub-district with a population of 3, 956 people. Although Ban Srisaket consists of six administrative mubaan, residents speak of themselves as members of the same community. Rice farming is the principal productive activity for households but poor soils and erratic rainfall constrain production to only one crop a year and household incomes are low. Like most similar communities in the Northeast, households rely on periodic migration to cities for waged labour.

My descriptions of these rites are based upon observations made during my residency in Ban Srisaket in 1992–93. Throughout my eighteen months of ethnographic fieldwork in this village, I frequently participated in rites marking the attainment of adult status; dancing around the village in celebratory ordination processions, and chatting to young mothers sweating by postpartum fires.

MATURED MEN: WATER SERPENTS

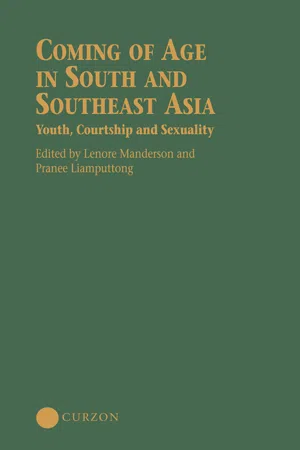

He is dressed in a dark coloured silk cloth with a white shawl across his shoulder (see Plate 1.1). On his face is a hint of makeup and he wears dark sunglasses. A white cloth covers his newly shaved head. His face remains expressionless, despite the fact that the palanquin upon which he sits dangerously sways and bounces as his six friends supporting it reel and rotate about in time to the music. He carries a black umbrella and in his hands he holds a black and white picture of a relative and a handful of plastic flowers. Ahead of him is a pickup truck with the abbot of one of the temples and another senior monk sitting in the tray. Behind them walk a small group of men, the young man’s sponsors and his father, one of whom carries a decorated monk’s bowl in the shape of a naag (water serpent).

Behind the palanquin carrying the young man are a crowd of women, dressed in their finest silk phaasin and bearing gifts, traditional pillows, flowers, robes, soap, toilet paper, washing powder, sprigs of jasmine. Following these women, another group of older women dance gracefully, shuffling in time to the furious rhythm of four drummers. The dust is stirred up in a cloud around us. Some of the grandmothers start drinking the whisky that is being passed around the procession. Behind the drummers come another crowd of wild-eyed men, some very drunk, dancing, pushing, passing around whisky and urging others to drink in insistent slurred tones. A couple of them move into the area where older women are dancing. One of the older women elbows the drunken young men, sending them giggling back to the end of the procession. Two transvestites dance, flirting and bawdily accosting men. One moves up to join the older women dancers. Village headmen move alongside the procession, policing activities and pulling one raucous young man aside. Finally, behind them comes a truck loaded with musicians playing music with a khaen and wort (traditional Northeastern wind instruments) and a loudspeaker.

Plate 1.1: Hae naag procession bearing young men for ordination as Buddhist monks.

People lay down straw mats in front of the procession for us to dance and walk over so that those who couldn’t join the procession might make merit too. Some people throw water on those in the procession, and young men make their way through the procession spraying white talcum powder on participants’ faces, sometimes with polite respect, more often with drunken glee. I’m not sure how to react as they pat it on my face and sprinkle it over my head.

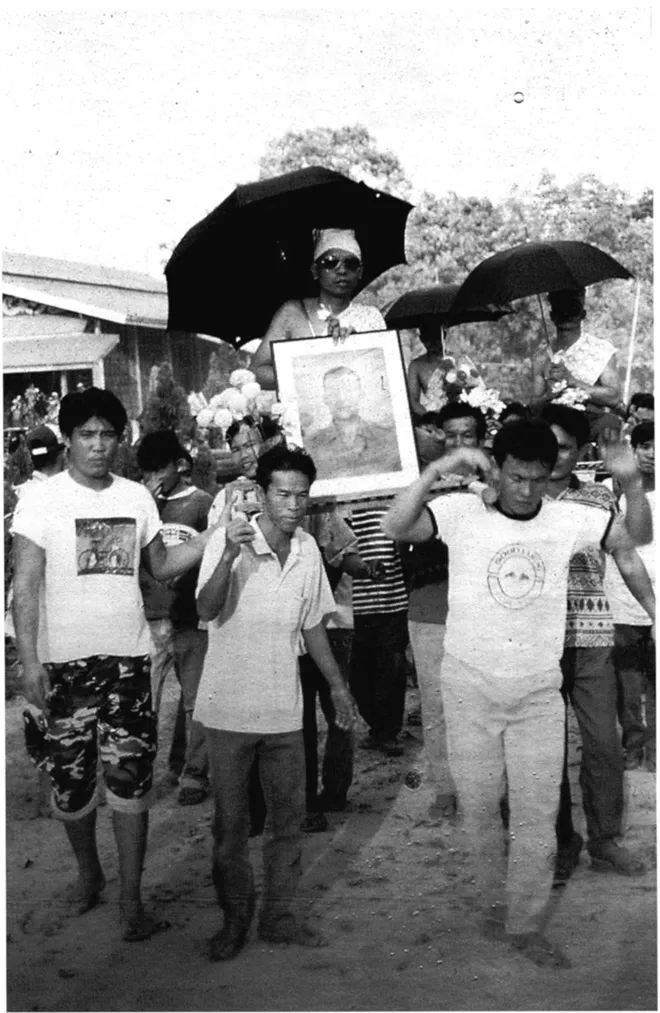

The procession enters the grounds of the oldest wat (temple) in the village circling the bot three times in a clockwise direction and then exiting the grounds. Then the procession goes all around the village until we reach the second temple ground that we circle once and then exit (Plate 1.2). Finally, after two hours of noise, dancing and play, the procession winds into the house compound of the boy’s parents where the gifts are placed in a specially erected tent. Older people sit with hands placed in the respectful wai gesture, listening to the monks chanting in another tent. Others wait for food and drinks. After the blessings and feasting, the young man enters the monastery and within the bot is ordained as a monk. Outdoor movies are shown until dawn in the village celebrations. (Field notes 1992)

Plate 1.2: Villagers in the procession circling temple grounds.

Such processions (hae naag) for young men being ordained into the Buddhist monkhood are hot, dusty, noisy and colourful events, regularly held during the dry season before the Buddhist Lent (phansaa) in the village of Ban Srisaket.2 The families and sponsors of the men devote huge financial resources to the gifts, procession, food and drink and late night entertainment such as movies or traditional singers (mor lam), even though some men might be ordained for as short as a week. Sometimes one young man is ordained, at other times, several families will join forces and four men will be ordained together, celebrating in a joint procession. These celebrations also mark emerging social stratification within the village, with wealthy families displaying conspicuous consumption in contrast to the more modest events held by poorer families.

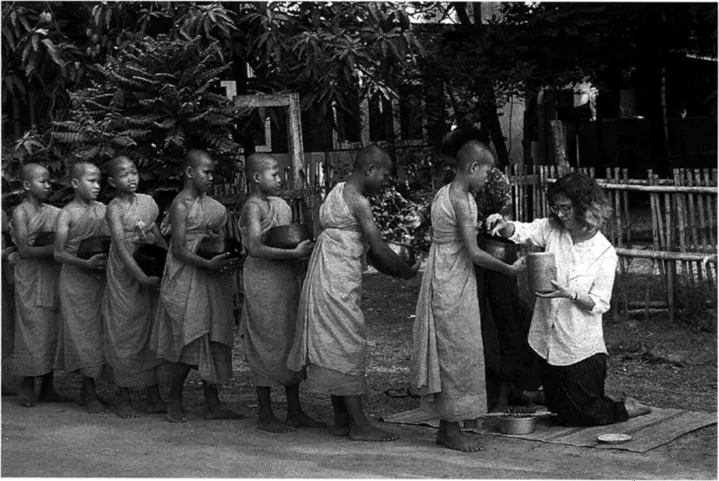

Monks are a crucial element of Buddhist belief in Thailand as they embody a ‘field of merit’ through which members of society may do good deeds and improve their merit. Being ordained as a Buddhist monk remains an important rite of passage for young men of Ban Srisaket. Unlike in more urbanized parts of Thailand where temporary ordination as a monk is in decline (Keyes 1984: 226), in Ban Srisaket, most men are expected to enter the sangha (the Buddhist clergy) as monks when they are 20 or 21 years old, prior to marriage and the beginning of family responsibilities. This is in addition to the ordination of most young boys as novices at least once during school holidays to receive training in Buddhist belief (Plate 1.3), and the common practice of entering the monkhood briefly to make merit upon the death of a relative. Most young men enter the Buddhist clergy for only a short time, such as a fortnight, and only a few now serve for one Lenten period or longer. Despite this, Ban Srisaket villagers proudly maintain that cin this village every man ordains’. Older men bemoan the fact that now few young men ordain for long enough to become truly skilled in monastic knowledge, many barely even master a few of the chants used in temple rituals.

Plate 1.3: Author earns merit feeding novice monks.

The initiand is called a naag, a water serpent, a mythological creature that lives underground and inhabits watercourses. This refers to a story in Buddhist mythology in which a water serpent ordained as a monk:

A naga, during the time of Buddha, assumed human form and was ordained as a monk. One day he was discovered in his true serpentine form when he was asleep. The Buddha expelled him from the Order, for only a human being can be a monk. But the naga pleaded that if his religious desires could not be fulfilled through monkhood, at least he should be remembered by calling every initiate nag [sic] before ordination. (Tambiah 1970: 173)

The naga symbol plays an important role in village rituals, legends, artefacts and architecture. In the temple in the village, the balustrades of the monk’s quarters were decorated in the form of a long naga, and the image is repeated in a number of ritual items. As Tambiah notes, the naga is depicted as both a pious devotee of Buddha and as representing animality, as a creature of the earth and waters with a vengeful temper when wronged (1970:173). He represents the life-giving forces of water and nature that are attracted to and tamed by Buddhism. This is exemplified in the well-known story of the serpent Muchalinda, who spread his cobra hood over the Buddha to guard him from a storm as he meditated and achieved enlightenment under the bo tree, as depicted in a concrete statue in the temple grounds in Ban Srisaket. Tambiah suggests that the naga symbolizes attributes of secular manhood, virility or sexuality, in opposition to the status of monk (phraa) (1970:107). The naga therefore represents the positive forces of male potency and regeneration. Secular discourses of masculinity within the village emphasize the body, the gratification of desires and worldly pleasures. The discipline of the Sangha thus ‘tames’ young men and...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Contributors

- Introduction: Youth and Sexuality in Contemporary Asian Societies

- 1 Water Serpents and Staying by the Fire: Markers of Maturity in a Northeast Thai Village

- 2 Poor and ‘Dark’: What is My Future? Identity Construction and Adolescent Women in Bangladesh

- 3 Adolescence and Sexuality in the Rajasthani Context

- 4 Inflatable Bodies and the Breath of Life: Courtship and Desire among Young Women in Rural North Bali

- 5 Modernity, Desire and Courtship: The Evolution of Premarital Relationships in Mataram, Eastern Indonesia

- 6 Contextualizing Sexuality: Young Men in Kerala, South India

- 7 Social and Cultural Contexts of Single Young Men’s Heterosexual Relationships: A View From Metro Manila

- 8 Gender Socialization and Female Sexuality in Northern Thailand

- 9 Magic Lipstick and Verbal Caress: Doubling Standards in Isan Villages

- 10 The Hope of the Nation: Moral Panics and the Construction of Teenagerhood in Contemporary Malaysia

- 11 Sexual Values and Early Experiences among Young People in Jakarta

- 12 Sex Work and Socialization in a Moral World: Conflict and Change in Bādī Communities in Western Nepal

- 13 Gender, Sexuality and Marriage among Hmong Youth in Australia

- Bibliography

- Index