![]()

THE ADOPTION OF FIBER LASERS

Until recently the industrial laser market was dominated by the traditional laser technologies of the last century, namely, gas lasers such as CO2 and solid-state lasers based on diode-pumped Nd:YAG crystals. These laser technologies were invented and optimized in the 1960s [1,2], becoming scientific research tools in the 1970s, and deployed as an industrial tool in the 1980s and 1990s. Today, the total annual industrial laser market is ~$2.6B (2014) [3]. The commercialization of the high-power fiber laser in the last decade is the first new laser technology to challenge the dominance of these traditional laser technologies. The market for fiber lasers was less than $100 M in 2005 but grew by 50% per year throughout most of the last decade. Indeed, it was only tracked as an individual laser segment from 2007, previously counting as part of the overall solid-state laser category. The annual sales of fiber lasers was ~$1B in 2014, over a third of the total industrial laser market share.

Why has this new laser technology been adopted so quickly by the relatively conservative industrial laser community? As will be seen throughout this book, fiber lasers are based on a series of specially designed optical fibers, together with a series of optimally designed fiber-based components, all spliced together in a monolithic chain. At the heart of the laser is a section of rare-earth-doped optical fiber acting as an active gain medium, similar to the function of the Nd:YAG crystal of the solid-state laser. However, several key parameters make the fiber laser very different in operation compared with the traditional diode-pumped solid-state laser (DPSSL) or traditional gas laser technologies.

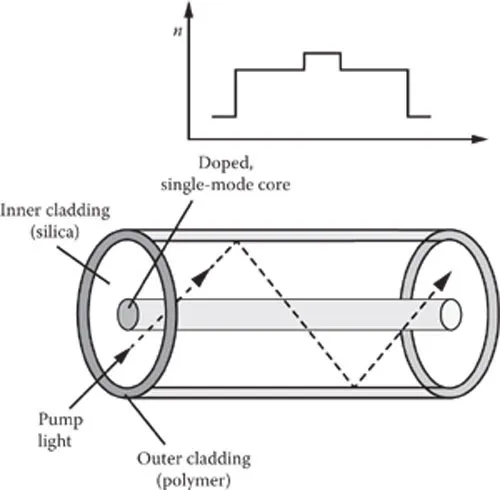

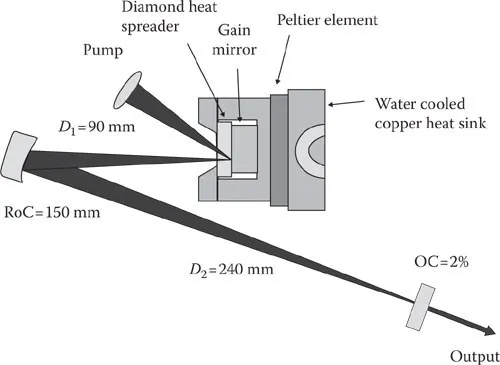

First, the core of an optical fiber acts as a waveguide confining the lasing mode and determining the output beam quality from a fiber laser, as shown in Figure 1.1. The use of fiber Bragg gratings (FBGs) written in the core of the optical fiber and acting as the reflectors for the laser cavity essentially eliminates the need for any free space components inside the laser cavity. This also eliminates any possible misalignment of the laser since these components are fusion-spliced together. Furthermore, the core waveguide reduces thermal effects on beam quality in the gain medium at high power levels, a major challenge in high-power DPSSL where thermal lensing in the YAG crystal is a major factor limiting the output power from single-mode lasers. Recent developments such as the disk laser [4] are an attempt to solve this by reducing the thickness of the gain medium, although at the expense of a more complicated multipass pump scheme and laser cavity, as shown in Figure 1.2.

The thermal load on the doped section of an optical fiber is primarily due to the quantum defect between the pump and lasing wavelengths. In the case of the fiber laser, this load is distributed over a relatively long length (several meters) compared with the Nd:YAG crystal used in a DPSSL laser or with the Yb:YAG in the disk laser. In addition, the very low losses of Yb-doped fibers mean that the laser slope efficiency far exceeds that of most DPSSL devices and the overall heat load on the fiber is low in addition to spreading over a longer length of doped material. The fiber surface is also relatively large and very close to the active core. This allows simple conductive cooling techniques to be applied to the fiber laser, which is helpful in designing air-cooled fiber lasers to operate at high power levels without the need for water cooling. This in turn enables smaller, more flexible, compact standalone laser designs compared with the alternative laser technologies. In addition, the use of monolithic, spliced fiber cavities allows for compact coiling of the complete laser without any need for alignment during the lifetime of the fiber laser.

These factors combine to decouple the beam quality from the output power of fiber lasers and greatly simplify the laser architecture for high-power single-mode lasers. Overall, the operation of single-mode fiber lasers at kilowatt-powers is now fairly routine, as can be seen by the number of companies offering this class of fiber lasers. The degree of engineering required to achieve kilowatt level single-mode lasers with DPSSL technology is beyond the level of engineering of many laser companies and they are not commercially viable, requiring the adoption of more advanced lasers such as the disk laser to enhance the heat removal from the laser crystal.

FIGURE 1.1 Schematic of double-clad fiber used in high-power fiber lasers.

FIGURE 1.2 Schematic of the high-power disk laser.

Unlike the disk laser, which is a patented laser technology [5], the fiber laser is relatively free of any overriding patent blocking the use of the technology. This is a major factor in the widespread and rapid adoption of fiber lasers, which in turn has helped to drive down the costs of the optical fibers and components needed to make fiber lasers by encouraging competition among suppliers, many of which were already making similar parts in support of the telecom industry.

The high efficiency associated with the fiber laser also has a major impact on the overall cost of the laser. In the case of most commercial DPSSLs, the laser is typically pumped by diodes operating around 800 nm and the laser emission is at 1064 nm, with a conversion efficiency of up to 25%. In the case of the fiber laser, the pump diodes are typically at around 940 nm and the lasing wavelength is also around 1064 nm, with conversion efficiencies typically exceeding 60% in many high-power systems. Based on this simple comparison, the required pump power is less than half for the fiber laser compared with that for the DPSSL, and, assuming similar costs for both laser diodes, we would expect a much lower cost for pumps in the case of the fiber laser. Historically, the pump laser diodes for fiber lasers have been more expensive than the 800-nm pumps for DPSSL but the price has been dropping dramatically over the past 10 years as the volume increases and the technology matures.

One major technological improvement that has occurred in the meantime is in the power extractable from a single-emitter diode operating around 940 nm. As the power/chip improved from 1 W in 1992 to the current >10 W without affecting the operating lifetime of the diode [4], the $/watt price of the diode dropped. Overall the cost has remained roughly the same for the diode chip, mounting, and fiber coupling, and, because each diode now produces 10× the power, we may expect the $/watt reduction to be in a similar range.

Although the cost of diodes for pumping fiber lasers has been dropping rapidly, they are still more expensive than the 800-nm diode bars used for the DPSSL, but this cost is partly offset by higher efficiency and reduced requirement for diode power. In the case of the disk laser, the adoption of Yb:YAG crystals allows for 940-nm pumping and similar high slope efficiencies as the fiber laser. As an additional benefit, the electrical-to-optical (E-O) conversion efficiency for diode lasers operating at 940 nm tends to be higher than those operating at 800 nm, giving a further improvement to the overall E-O efficiency for the fiber and disk laser when compared with the commercial DPSSL. Many high-power fiber lasers have overall E-O efficiencies in the range of 25–30%, with some up to 50% [6].

The other factors to consider are the reliability and the running costs of the laser system. In the case of the fiber laser, we have already highlighted the impact of high efficiency on the performance and cost of the laser. These efficiencies also translate into lower electricity costs for operating the laser. In cases where factories are operating many multi-kilowatt laser systems 24 hours/day and 7 days/week, these cost savings are significant over the lifetime of the laser. The comparison with CO2 lasers is even more dramatic because they have a low E-O conversion efficiency of only up to 20% for commercial kilowatt systems [6].

The overall cost of ownership of the laser must also include wear and tear on the laser, replacement part costs, etc. One major advantage of fiber laser pump diode technology is the use of singleemitter diodes rather than the traditional bar technology used in most DPSSLs. As we will discuss later in the book, the adoption of individual emitter-based pump diodes greatly improves the reliability of diode lasers compared with previous generations of lasers and extends the operating lifetime by further adopting telecom-type reliability models. The adoption of these highly reliable pumps greatly improved the lifetime of the lasers themselves and has been a major factor in the adoption of fiber lasers compared with alternatives. Indeed, the reliability of these pump diodes has led to an overall trend within other laser technologies to switch to single-emitter-based pumps where possible. The perception that pump lasers are no longer a replaceable and wear-out part of the system has been a great encouragement to the adoption of laser technology.

With all these factors in its favor, the single most significant factor driving the adoption of this technology has been the improvement in output power from a single-mode fiber laser, which has allowed the technology to compete in major industrial applications, such as cutting and welding at the kilowatt output level.

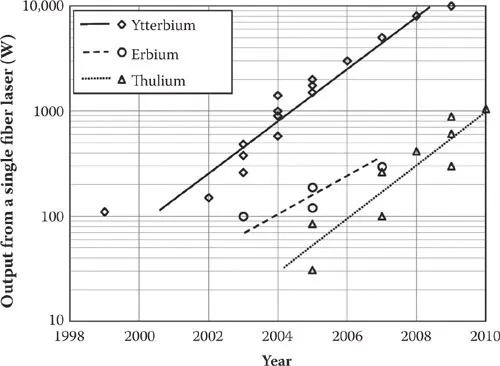

The period from 2000 to 2010 saw an unprecedented advance in high-power fiber laser technology. As shown in Figure 1.3, the continuous wave (CW) power from a single Yb-doped fiber laser operating at around 1 μm and delivering nearly single-mode beam quality increased from ~100 W in 1999 [7] to 10 kW in 2010 [8]. This rapid increase in output power was enabled by several factors, but it is also important to note that many of these high-power results were limited only by the available pump power rather than any engineering or physical limit of the fiber itself. To this extent, progress on scaling output power from a single-mode Yb-doped fiber was closely tied to the available laser diode power and specifically to the progress on suitable high-brightness diodes that could be efficiently coupled into a single Yb-doped fiber.

FIGURE 1.3 Power scaling of single-mode fiber lasers with time.

HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENTS IN OPTICAL FIBERS

To understand the growth of fiber lasers over the past 10 years, it is important to understand the roots of the technology and the role of the telecommunications industry in developing many of the key technologies. One of the first references in the literature to consider a glass optical fiber as a practical optical transmission medium dates from 1966 by Charles Kao [9], who received the Nobel prize for Physics in 2009 for his work on fiber optics at Standard Telecom and Communications Laboratory (STC) in the UK. This groundbreaking work furthered our understanding of the material and waveguide losses in glass fiber and gave a bold projection, for the first time, that these losses could be reduced to a level that would allow signal transmission in fiber over distances relevant to long-haul telecommunications. However, it was not until around 1970, with the demonstration by Corning labs [10] of material losses below 20 dB/km for titanium-doped silica glass optical fibers, that the full potential for this transmission medium in the telecommunication industry was experimentally realized. For the next decade, major research laboratories throughout the world, such as AT&T Bell Labs (Murray Hill, NJ), Corning Inc. (Corning, NY), STC and British Post Office Labs in the UK as well as the major telecom laboratories in France and Japan, were engaged in research to produce silica glass optical fibers with ever-decreasing losses. First, this was done in multimode fibers but then research moved to single-mode optical fibers as the telecom industries realized their benefits in long-haul transmission. During this time, great strides (and many inventions) were made on the optimization of industrial scale fabrication processes for making these ultra-low-loss fibers. This decade of fiber optics research resulted in the first deployed phone link in 1977, the first long-haul fiber optic link in the early 1980s, and the first transatlantic cable in 1988. For an excellent history of this topic area, see the book City of Light by Jeff Hecht [11].

This large-scale R&D led to a wealth of understanding on the sources of loss in ultra-pure silica glass fibers, including the contributions from intrinsic (Rayleigh scattering losses) and extrinsic sources such as impurities. The lowest loss in silica fibers occurs at around 1550 nm, and this is the preferred transmission window for long-haul fiber optic links. Other telecommunication windows at 1300 and 800 nm are traditionally used in shorter links. Importantly for today’s emerging fiber laser industry, this investment in telecom fiber technology has put in place the critical infrastructure and processes for making ultra-pure silica optical glass fibers in very high volumes. Today single-mode and multimode silica fibers are made in multiple locations throughout the world using a variety of different processing techniques, many of which were developed and patented during those early days of the technology. The largest single application for optical fiber is telecommunications, where a single cable carrying signals over lengths of hundreds of kilometers clearly demands ultra-low levels of attenuation. Today state-of-the-art commercial single-mode fibers achieve low loss limits of ~0.2 dB/km at 1550 nm [12], and research continues on how to reduce this figure even lower, with the...