![]()

Section II

Remote Sensing for Sustainable Natural Resources

![]()

6 | Role of Remote Sensing in Sustainable Grassland Management A Review and Case Studies for a Mixed-Grass Prairie Ecosystem Alexander Tong, Bing Lu, Yuhong He, and Xulin Guo |

CONTENTS

6.1 Introduction

6.2 Case Studies

6.2.1 Assessing Grassland Health Using Remote Sensing–Derived Biophysical Properties

6.2.2 Mapping Chlorophyll Content as an Indicator of Grassland Health

6.2.3 Investigating Grassland Disturbance Using Remote Sensing

6.2.4 Determining the Effects of Climatic Factors on Grassland Health Using Remote Sensing

6.2.5 Mapping Habitat for Endangered Species Using Remote Sensing

6.3 Conclusions, Challenges, and Opportunities

6.3.1 Conclusion

6.3.2 Challenges and Opportunities

6.3.2.1 Image Acquisition and Processing

6.3.2.2 Species-Level Monitoring

6.3.2.3 Vegetation Structure Mapping

6.3.2.4 Snow, Topography, and Soil Moisture Mapping

6.3.2.5 Logistics

Acknowledgment

References

6.1 INTRODUCTION

Grasslands are critically important ecosystems that serve as habitats for a variety of species of perennial grasses and other herbaceous vegetation, birds, animals, and insects. However, a majority of grassland biomes have been transformed, converted, or altered by human intervention on a global scale, with very few natural intact areas remaining. In North America, the grassland biome was once the most extensive, but has become one of the most threatened ecosystems (Samson and Knopf 1994). Since the remaining grassland ecosystems are inherently fragile, effective management strategies are important to address impacts driven by anthropogenic activities such as over-grazing, urban expansion, agricultural intensification, invasive species, and wildfire suppression under a changing climate. In fact, grassland management strategies have been moving toward integrated ecosystem and landscape-based approaches to address the impacts by focusing on areas such as biodiversity conservation, habitat restoration, and sustainable resource management (Bizikova 2009; Estrada-Carmona et al. 2014; Jun 2006). Such broad-scale plans bring partners and stakeholders together to realize common and shared objectives that consider both local and landscape-wide needs.

Monitoring grassland changes across space and time is the first step leading to effective management plans. Since grasslands are central to the livelihoods of more than a billion low-income people, managing grasslands has been a balance between competing demands, especially between economic returns and ecosystem services. Traditional ways of grassland monitoring that rely on field surveys are typically expensive and labor-intensive. In addition, field-based methods only provide localized information that presents a challenge when extrapolating it over large areas, and the information is thus often insufficient for land managers. Alternatively, remote sensing has become increasingly important for grassland ecosystem monitoring and guiding sustainable management practices (Boval and Dixon 2012). Once remote sensing technologies and techniques are validated at a local level, they can be easily generalized and used for long-term monitoring at a range of spatial and temporal scales.

Remote sensing imagery with a variety of spatial and temporal resolutions can be utilized for different management purposes with modest budgets. For practical and economic reasons, multispectral image data including Système Probatoire d’Observation de la Terre (SPOT), Landsat, Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS), and Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) images acquired from spaceborne sensors are commonly used for studying large geographical areas. Whereas SPOT and Landsat images offer high and medium spatial resolution data, respectively, they also have correspondingly lower temporal resolutions in comparison to the coarse spatial, but high temporal resolutions of MODIS and AVHRR data. Still, the most extensively used satellite imagery for research and application has been Landsat, as it offers a long historic archive that can be used to map long-term spatiotemporal vegetation changes. More capable sensors that could resolve ground features more accurately are spaceborne sensors offering very high spatial resolutions such as GeoEye-1, WorldView-2/3, or Pleiades-1A with spatial resolutions of 0.41, 0.46, and 0.5 m, respectively. Less commonly used for study because of the high cost of acquisition is airborne hyperspectral imagery such as AVIRIS or CASI, which provides very high spectral and spatial resolution data, but is consequently not practical for long-term studies/monitoring application. Recently, lightweight digital cameras and hyperspectral sensors that can be mounted on unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) have been utilized for grassland surveys (Laliberte and Rango 2011; Laliberte et al. 2011; Rango et al. 2006; Von Bueren et al. 2015). UAVs as an emerging remote sensing platform can provide imagery with spatial resolution higher than 0.1 m, which is an unprecedented data source for species-level research. Such platforms are capable of providing very high spatial resolution images at required temporal resolutions that can be used for finer-scale grassland investigation. However, the current acquisition cost and processing time for such high spatial resolution imagery may be only appropriate for hot spot monitoring, but untenable for long-term large-area monitoring.

Over the past decade, studies using remote sensing for grassland management have been conducted all over the world, including North America (Listopad et al. 2015; Mirik and Ansley 2012), South America (Bradley and Millington 2006; Di Bella et al. 2011), Europe (Psomas et al. 2011; Redhead et al. 2012), Asia (Cui et al. 2012; Leisher et al. 2012; Zhang et al. 2008), Africa (Olsen et al. 2015), and Australia (Guerschman et al. 2009; Lawes and Wallace 2008). Remote sensing of spatiotemporal changes in vegetation attributes such as biochemical (e.g., chlorophyll pigment) and biophysical (e.g., leaf area index [LAI]) properties, plant biomass, canopy cover, and vegetation height can inform ecosystem status. Additionally, these attributes can be applied to monitor the effects of wildfire disturbances, habitat loss, or climate change on grasslands. In these studies, the most commonly used remote sensing technique for ecosystem monitoring applications has been the use of empirical–statistical models. These models involve establishing a relationship between in situ biochemical or biophysical measurements with spectral vegetation indices calculated using ground-level spectral reflectance measurements or optical remote sensing imagery.

Intensive research using remote sensing within the past decade has been conducted in an endangered mixed-grass prairie ecosystem to evaluate vegetation conditions across space and time in relation to local environmental factors, climate conditions, and disturbance events. The implications of the research for validating remote sensing technologies and techniques for the mixed-grass prairies are providing valuable information and insight to land managers for guiding future management practices; several bodies of this research are presented in the following section.

6.2 CASE STUDIES

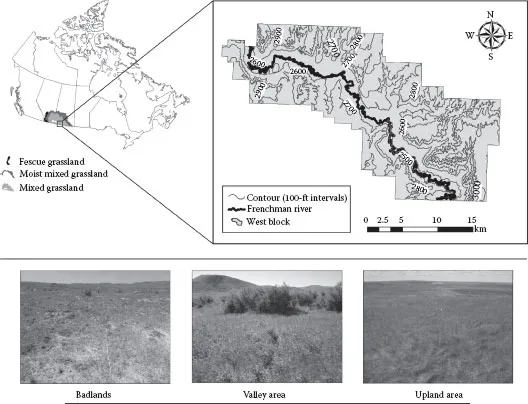

Of the three North American prairie types—tallgrass, mixed-grass, and shortgrass, the mixed-grass prairies have seen some of the worst decline, with remnants still found in parts of southern Alberta and Saskatchewan, Canada. The Government of Canada recognized the ecological importance of preserving an intact area of the endangered mixed-grass prairie ecosystem in 1981 and the Grasslands National Park (GNP, N 49°12′, W 107°24′) was soon established in 1988 (Figure 6.1). However, portions of the GNP are fragmented into small parcels as a consequence of land within and neighboring the park boundaries being privately held and used for agricultural or grazing purposes. Nevertheless, Parks Canada, an agency of the Government of Canada, has been tasked with operating and protecting the GNP in efforts to conserve and restore the rich diversity of species and highly specialized communities of plants and animals in their native state that have evolved in response to a variety of stresses, such as drought, grazing, and fire (Anderson 2006; Shorthouse and Larson 2010).

FIGURE 6.1 Map delineating the extent of the mixed grass prairies in Canada, the GNP, and three typical landscape units including badlands, valley area, and upland area in the GNP.

Here, we introduce a select number of studies demonstrating the application of remote sensing technologies and techniques for the management of the mixed-grass prairies at the GNP. From a remote sensing perspecti...