I

Introduction

The Long Road to Maya Markets

SCOTT R. HUTSON AND BRUCE H. DAHLIN

The occupation to which [the Maya] had the greatest inclination was trade. (Landa in Tozzer 1941:94; see also Roys 1943:51–53)

All but a small minority of the Maya, before or after the conquest, were simply outside a market economy with little to sell and little need to buy. (Farriss 1984:156; see also Restall 1997:185).

This book argues that market exchange was a significant aspect of the Classic Maya world. The essays that follow draw on broad-ranging, interdisciplinary datasets from the ancient Maya city of Chunchucmil to illuminate some of the thorny questions about ancient economies signaled by the tensions between the two quotations above (see also Hirth 2010; Hirth and Pillsbury 2013a; Masson and Freidel 2012; Shaw 2012). Were Classic Maya households mostly self-sufficient in the sense that each acquired the raw materials and produced the finished goods necessary for daily life? Or was exchange a critical factor in provisioning Maya society? If exchange was essential, what was the relative importance of the various forms that exchange can take, such as reciprocity, redistribution, and marketing? If markets were important, how often did they take place? What was their geographic reach? Who controlled and/or benefited from them? The significance of these questions cannot be underestimated. The ancient Maya spent many of their waking hours provisioning themselves, and human beings have devised a spectacular array of strategies for doing this, from farming to multicrafting to alienating their labor in capitalist economies. If we do not know how the Maya approached production, we will not know, in a very basic sense, what most people were doing with so much of their time. Furthermore, if we do not know how goods moved from producer to consumer, we miss out on basic links between different segments of society as well as a knowledge of what segments remain unlinked (Hirth and Pillsbury 2013a:4; Shaw 2012:118). If we do not look closely at exchange, we miss out on a chance to learn about the power and decisions of a broad variety of actors.

One reason why we know so little about production and exchange among the ancient Maya is that they worked with many biodegradable materials. Preservation conditions have erased wood, textiles, hides, fuel, fruits, seeds, nuts, vegetables, spices, dyes, gourds, cordage, bags, bundles, baskets, and, often, bone—materials that formed the core of Maya lives and livelihoods (Dahlin et al. 2007; Foias 2002; King 2015:53). The two quotations at the beginning of this chapter highlight deep differences in scholarly opinion about the degree of commercialization in ancient Maya society. Usually when such different views coexist within a discipline, it is because gaps in knowledge are so fundamental that they prevent falsification of any stance whatsoever. In this case, the biggest gap comes from the archaeological invisibility of most traces of what the Maya spent so much of their time doing. The preservation issue points at the deeper epistemological question that lurks under the surface of scholarly disagreements: if poor preservation has erased the best data on ancient Maya lives, how can we study ancient economies? More specifically, how can we determine the degree of commercialization at a particular Maya site? In this book we approach the challenge of missing data by turning to a variety of other lines of evidence that, with the right questions and bridging arguments, can be made to speak to the issues.

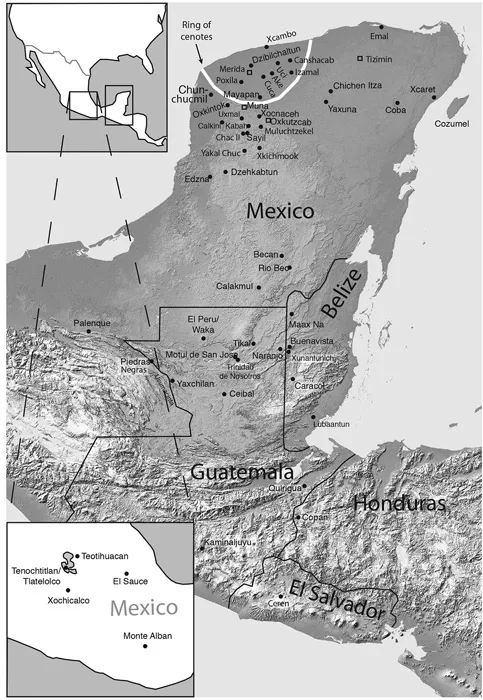

Not long ago, general accounts of the Maya (e.g., Henderson 1981:152) saw commerce as an important component of Maya economies in the centuries immediately prior to contact with the Spanish—the Postclassic period—but not in the Classic period, from 250 to 900 ce. Several well-known historical sources from the contact period underscore the prominence of long-distance exchange. For example, members of Christopher Columbus’s fourth voyage to the New World met up with a Maya canoe full of trade goods off the coast of Honduras (Colón 1959:231). Also around the time of contact, a member of one of Yucatán’s ruling families, the Cocom, escaped certain death because he was away on a coastal trading mission when the rest of his kin were ambushed and assassinated by members of the rival Xiu family (Roys 1962:48). Furthermore, Ralph Roys (1943:51) cited Spanish historical documents that speak of the existence of large markets near the coast in northeastern Yucatán and others in the interior. Ethnohistorical material for the Maya highlands suggests that a majority of households depended on marketplaces for everyday needs (King 2015:38). The importance of trade indicated in these historical sources receives support from the archaeology of the Postclassic period, which has documented a rise in obsidian exchange, the appearance of bustling centers on coastal trade routes, and changes in ceramic production geared toward exports (Masson 2001; Masson and Chaya 2000; Masson and Peraza Lope 2014:26; McKillop 1996; Rathje 1975; Sabloff and Rathje 1975; West 2002).

In contrast, scholars have characterized the economy of the preceding Classic period as relatively uncommercialized. About 25 years ago, many archaeologists wrote about the exchange of prestige goods among nobles in the upper crust of Maya society, but few (Fry 1979, 1980) explored the exchange of non-prestige goods across the rest of Maya society (Shaw 2012). In her synthesis of Late Classic–period Maya economies, Rice (1987:77) detailed some of the problems in reconstructing non-elite exchange, including a lack of evidence for architecture that could be clearly identified as storehouses or marketplaces, a lacuna in the hieroglyphic record with regard to economic affairs, and little evidence that producers located their activities near areas where consumers might congregate. Some earlier work did in fact highlight the importance of long-distance exchange of non-prestige goods: William Rathje (1971) assigned it the chief role in the development of complex Maya societies. In his view, people in the southern lowlands developed temples, hieroglyphic writing, and astronomical knowledge in exchange for salt, obsidian, and grinding stones. Though some lines of data did not align with Rathje’s argument (serviceable grinding stones, for example, were very often made with locally available stone), his early arguments still provide valuable insights (Freidel 2002; Freidel et al. 2002; Hutson et al. 2010:81; Masson 2002a:14). In any event, redistribution, as opposed to marketing, was thought to dominate exchange across the Maya area in the Classic period.

Nevertheless, markets have not been invisible in earlier writing about Classic-period Maya economies. For example, expanding on a very brief passage written by J. Eric S. Thompson (1966:22), David Freidel (1981) argued that when massive ceremonies and rituals drew rural settlers to religious centers, marketplaces most likely accompanied these events. To support this position, Freidel referred to the conjunction of markets and religious events in medieval Europe and historic and contemporary Guatemala. Though Freidel’s argument did not refer to any particular archaeological site, other authors writing at about the same time as Freidel proposed that specific plazas at specific sites, such as Tikal (Jones 1991), Sayil (Wurtzburg 1991; cf. Terry et al. 2015), Cobá (Folan et al. 1983), and Seibal (Tourtellot 1988) served as marketplaces (figure 1.1).

For reasons discussed later in this chapter, those who argued that marketplaces played an important role in Maya economies faced an uphill battle. Everyone agreed that some degree of economic exchange took place at various levels of society—interregional trade among nobles for exotic goods (Hammond 1972a), intraregional trade among the hoi polloi for utilitarian pottery (Rands and Bishop 1980), and redistribution between these two social strata—but few argued that commerce was central to subsistence. Yet neither of the positions from a quarter century ago—little commerce versus lots of commerce—could make headway because of a shortage of research specifically designed to tackle this question. As Patricia McAnany wrote in 1993, “we have only very rudimentary notions about the economic organization of the [Classic] Maya household and polity. This state of the art, in part, is due to the fact that we simply haven’t been aggressively asking questions or structuring focused programs of inquiry regarding the Classic Maya economic system.”

In the same year that McAnany published her call for research designs closely focused on economic systems, Bruce Dahlin (1941–2011) began working at the ruins of Chunchucmil. Dahlin’s project came to be known as the Pakbeh Regional Economy Program (PREP).1 Located 70 km southwest of the modern city of Mérida, the ruins got their name from a twentieth-century henequen plantation (now a village of 1,200 people) located 2 km to the west of the ancient site center....