eBook - ePub

Anthropomorphizing the Cosmos

Middle Preclassic Lowland Maya Figurines, Ritual, and Time

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Anthropomorphizing the Cosmos

Middle Preclassic Lowland Maya Figurines, Ritual, and Time

About this book

Anthropomorphizing the Cosmos explores the sociocultural significance of more than three hundred Middle Preclassic Maya figurines uncovered at the site of Nixtun-Ch'ich' on Lake Petén Itzá in northern Guatemala. In this careful, holistic, and detailed analysis of the Petén lakes figurines—hand-modeled, terracotta anthropomorphic fragments, animal figures, and musical instruments such as whistles and ocarinas—Prudence M. Rice engages with a broad swath of theory and comparative data on Maya ritual practice.

Presenting original data, Anthropomorphizing the Cosmos offers insight into the synchronous appearance of fired-clay figurines with the emergence of societal complexity in and beyond Mesoamerica. Rice situates these Preclassic Maya figurines in the broader context of Mesoamerican human figural representation, identifies possible connections between anthropomorphic figurine heads and the origins of calendrics and other writing in Mesoamerica, and examines the role of anthropomorphic figurines and zoomorphic musical instruments in Preclassic Maya ritual. The volume shows how community rituals involving the figurines helped to mitigate the uncertainties of societal transitions, including the beginnings of settled agricultural life, the emergence of social differentiation and inequalities, and the centralization of political power and decision-making in the Petén lowlands.

Literature on Maya ritual, cosmology, and specialized artifacts has traditionally focused on the Classic period, with little research centering on the very beginnings of Maya sociopolitical organization and ideological beliefs in the Middle Preclassic. Anthropomorphizing the Cosmos is a welcome contribution to the understanding of the earliest Maya and will be significant to Mayanists and Mesoamericanists as well as nonspecialists with interest in these early figurines

Presenting original data, Anthropomorphizing the Cosmos offers insight into the synchronous appearance of fired-clay figurines with the emergence of societal complexity in and beyond Mesoamerica. Rice situates these Preclassic Maya figurines in the broader context of Mesoamerican human figural representation, identifies possible connections between anthropomorphic figurine heads and the origins of calendrics and other writing in Mesoamerica, and examines the role of anthropomorphic figurines and zoomorphic musical instruments in Preclassic Maya ritual. The volume shows how community rituals involving the figurines helped to mitigate the uncertainties of societal transitions, including the beginnings of settled agricultural life, the emergence of social differentiation and inequalities, and the centralization of political power and decision-making in the Petén lowlands.

Literature on Maya ritual, cosmology, and specialized artifacts has traditionally focused on the Classic period, with little research centering on the very beginnings of Maya sociopolitical organization and ideological beliefs in the Middle Preclassic. Anthropomorphizing the Cosmos is a welcome contribution to the understanding of the earliest Maya and will be significant to Mayanists and Mesoamericanists as well as nonspecialists with interest in these early figurines

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Anthropomorphizing the Cosmos by Prudence M. Rice in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Introduction

Background, Contexts, and Theories

Motion was an inherent quality of life, and energy and spirit continually moved through the twin fields of time and space.

Ringle 1999: 188

What can we learn about the early lowland Mayas from ceramic figurines? The answer proposed here is that these objects played a role in time- and calendar-related public rituals. This proposition was developed through analysis of a corpus of 377 low-fired (well below 1000˚C) clay figurines and fragments recovered from two archaeological sites in northern Guatemala. The analyzed artifacts include 255 largely fragmentary, handmade, anthropomorphic (modeled on the human body) figurines, thought to represent important beings such as ancestors and supernaturals, plus 132 zoomorphs, musical instruments, and other pieces. They date primarily to the Middle Preclassic period, ca. 800–400 BC, although a few were made earlier.

Part I establishes the spatio-temporal occurrences and theoretical/interpretive contexts of these small objects. Chapter 1 opens with a query, Why figurines? Cross-culturally, the widespread early manufacture of fired-clay anthropomorphic figurines, particularly females, accompanies the transition to sedentary village life and the protracted, stressful circumstances of emerging societal complexity. Discussion moves to concepts aiding the interpretation of figural representations, commonly recovered as discarded fragments. Chapter 2 backgrounds the interpretation of these artifacts in Preclassic/Formative Mesoamerica through two foci: the role of ritual, highlighting aspects of selectionist theory such as costly signaling and cooperation; and grounding in earlier pre-village, hunter-gatherer adaptations and observations of the natural world as they pertain to calendar development.

Chapter 1

Why Figurines?

Worldwide, the human body has provided a model for conceptualizing and categorizing the organization of natural, social, and cosmic spaces (e.g., Csordas 1990, 1994b; López Austin 1988; Mauss 1973; Robb and Harris 2013). A “key symbol” (see Ortner 1973: 1339–40) in art and religion, the human body synthesizes several dialectical relations: it is both model of and a model for reality (Geertz 1973: 91–94), and it is both physical and social—“the physical body is a microcosm of society”—with these dual meanings continually exchanged (Douglas 1973: 93, 101; see Sandstrom 2009: 263–64). Depicted in varied media—clay, paint, wood, stone; from miniatures to monoliths; from two-dimensional stick-figures to low-relief and in-the-round sculptures—the human figure and particularly the human head and face have dominated the visual arts for millennia.

Early Figurines Cross-Culturally

Anthropomorphic figurines were produced in many times and places throughout the premodern world. Of interest here is the co-occurrence, in both Eurasia and Mesoamerica, of figurines with times of dramatic cultural changes. One such period falls at the end of the Pleistocene (in Eurasia); the other, later and more widespread, comes at the time/stage of early-middle Holocene “neolithic” transformations associated with emerging cultural complexity.

As far as is currently known, human figures modeled of clay began to be made in Eurasia during the Late Upper Paleolithic era as components of a broader realm of conceptual, figurative, and representational artistic expression in varied media (see, e.g., Borić et al. 2013; Budja 2010: 507–10; Kashina 2010; Soffer, Adovasio, and Hyland 2000; Vandiver et al. 1989; White 2008). Often dubbed “Venus” or “fertility goddess” figures and recovered from central Europe to Siberia, these objects typically depict voluptuous females with pendulous breasts, broad hips, generously rounded abdomens, and large buttocks and thighs. These Rubenesque characteristics, viewed through the male gaze as accentuating female fecundity, led to early interpretations of the figurines as fertility fetishes. They were carved of stone and ivory as well as shaped in clay and sometimes coated with red ochre. Their appearance coincides with a semiotic transformation manifest in the emergence of new signs, symbolic activities, means of communication, and self-referential art (Wildgen 2004: 113–14; see also Overmann 2013). Representations of females may constitute “a new level of collective perception . . . linked to norms valid for sexual selection,” but they may also reflect new social and economic roles for males and females associated with settlement and subsistence shifts accompanying climate changes at the end of the last glaciation (Wildgen 2004: 115, 120).

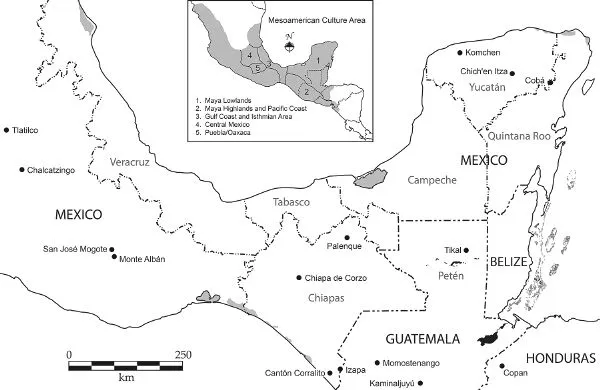

Several thousand years later, fired-clay anthropomorphic figures were widespread during major Braudelian (Braudel 1972) long-term conjonctures and longue durée: the radical transformations in lifeways associated with the early Old World Neolithic. These developments include the beginnings of food production and animal husbandry, year-round sedentary village settlements, construction of permanent domestic and public architecture, material culture elaboration, new gender roles, and the interpenetrating processes of social and economic differentiation (ranking), centralization of political power in permanent leadership positions, and loss of village autonomy. Dependent on agriculture (itself partially a response to early Holocene climate change), these “emergent properties” led to “new rules of social behavior, the appearance of new rituals, ceremonies, and beliefs, the co-ordination of labor to schedule tasks and promote exchange, the alteration of the natural and cultural landscape, the beginnings of new statuses and social relationships, and expansion into new regions . . . [and] the formation of ‘interaction spheres’ in which the identities of villagers were significantly altered, and new social and political relationships emerged” (Yoffee 2005: 204). Figurines are found virtually worldwide in association with these developments in village societies and preceding the rise of cities and civilizations—for example, in the Near East (e.g., Kuijt and Chesson 2005; Rollefson 2008), the Indus valley (Clark 2003, 2009), southern Europe (e.g., Biehl 1996; Chapman 2000: 68–79; Gimbutas 1974), and Jomon Japan (Chapman 2000: 25–26; Habu 2004: 142–52, 250–52). And also in Formative (or Preclassic) period Mesoamerica (figure 1.1).1

Figure 1.1. The Mesoamerican culture area, showing modern political borders and sites mentioned in the text.

In many parts of the world, the ubiquitous Neolithic-stage terracotta figurines, like those of the Upper Paleolithic, extend the general elaboration of the human body and secondary sexual characteristics, especially of females. Hands, arms, and feet are minimized and the head, if present, is often only a small projection between the shoulders, with little or no delineation of facial or other features. This is not to say that the human head was of no interest; instead, it may have been given separate and very different treatment. In the Neolithic southern Levant (Near East), for example, skulls were removed sometime after primary burial, and at Jericho adult skulls that had undergone cranial modification in childhood were covered with plaster and buried as objects of memory (Fletcher, Pearson, and Ambers 2008; Kuijt 2008; Kuijt and Chesson 2005: 175).2 Some figurines may have been portrayals of specific individuals (see Bailey 1994; Biehl 1996), perhaps leaders, ancestors, shamans, or other ritual specialists, any of whom could have been of either sex. In all such early settings, these objects are thought to have played active roles in the constitution of social life, engaging in rituals and performances—the details of which are now lost—that furthered the creation of social identities, links with the past, and “meaning-making” in domestic and public spheres (e.g., Biehl 1996, 2011).

The many variations on this generalized pattern should not be ignored. In the early Bronze Age Balkans of southeastern Europe, “figurines appear with the first settled, pottery-making farmers and they disappear abruptly with the abandonment of the Neolithic way of life” (Bailey 2005: 3). In South Asia, the earliest Neolithic (7000–5500 BC) occupation at the site of Mehrgarh (Pakistan) is characterized by farming villages in which female figurines were made even before the appearance of pottery containers, although these objects, including males, continued to be made throughout the Indus, or Harappan, civilization (Clark 2009). Jomon Japan provides another variant on the theme, with widespread and apparently primarily female clay figurines (dogū) of the Middle through Final Jomon periods (ca. 3000 BC–AD 0) accompanying developing social complexity and sedentism largely based on collecting storable plant foods (Habu 2004: 77–78, 142–49, 252–60). In western Mesoamerica, these artifacts are found in a culturally analogous stage or period known as the Formative (ca. 2500 BC–AD 100/200).

Why figurines, especially female, in these spatially and culturally differentiated but broadly shared Neolithic circumstances? An early interpretation, originally proposed by Sir Flinders Petrie and promoted by Marija Gimbutas (1974) but now discredited (Conkey and Tringham 1995; Marcus 2018: 6; Ucko 1962; see also Ştefan 2005–6), focused on the transformations characterized by a shift in sociopolitical roles from females to males in non-sedentary or sedentarizing societies. This involved the decline of earlier matriarchy and a mythical female goddess—connected with natural forces, earth, and fertility; a “Great Mother” or Mother Goddess—and the rise of patriarchy. The shift accompanied a rejection of female leadership and property ownership (for example), replaced by an emphasis on males in these positions of authority.

These transformations underlie a provocative thesis proffered by Leonard Shlain (1998) but explained through different mechanisms. Shlain proposes that the submergence of a “feminine principle” by the masculine occurred at the threshold between orality and literacy, coinciding with early stages in the development of alphabetic writing and literacy as mechanisms for exercising power. These latter placed an advantage on linear, left-brain thinking, leaving visual, artistic, and iconic imagery demoted. What resulted was, in essence, a conflict over “the alphabet versus the goddess” (Shlain 1998).3 Changes in communication modes and media appear to be key, as in the “semiotic transformations” in the Late Paleolithic. Figurines (especially females) gained prominence in material culture assemblages—and visual discourse—dating to these major sociopolitico-economic metamorphoses. Writing systems also often originated in such eras (Houston 2004: 239). Is this coincidental, or might there be similar causal factors underlying both?

Joyce Marcus’s studies of early anthropomorphic figurines, especially in Oaxaca (highland Mexico), have identified cross-culturally valid empirical and gender-based propositions concerning their occurrence. For example, figurines are particularly associated with village societies and ancestor-based descent groups (Marcus 2018: 4). Ancestors could “intercede with the spirit world on behalf of their descendants” by being coaxed, with offerings and favors, to occupy a “physical venue, such as a figurine” (Marcus 2018: 4–5). Women generally carried out rituals honoring recent ancestors in domestic contexts, whereas men’s rituals focused on more remote lineage founders and were held in special structures (Marcus 2018: 5). Hand-modeled female figurines were most common in village societies, whereas mold-made and male figurines tended to be associated with cities and state-level societies (Marcus 2018: 7, 9). The end of handmade (primarily female) figurine manufacture can be associated with changes in ancestor status, as ancestors turned into the founders of royal dynasties (Marcus 1998: 21). At the same time, female figurines’ end may be related to the “rise of a dominant organized religion” (Proskouriakoff 2001: 342).

A study of the impact of modernization on an early to mid-twentieth-century Tzeltzal Maya community in highland Mexico (Nash 1967) provides insights into the social tensions resulting from pervasive cultural changes in village societies and their effects on the sexes. This small, relatively isolated village experienced increasing contacts with national and regional Ladino authorities, who i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Part I. Introduction: Background, Contexts, and Theories

- Part II. Formative Mesoamerican and Maya Human Figures and Figurines

- Part III. Time, Formative Heads, and Maya Writing

- Part IV. Additional Perspectives for Interpreting Early Maya Figurines

- Part V. Conclusions

- Appendix: Concordance of Figurine Numbers, Illustrations, and Provenience Information

- References

- Index