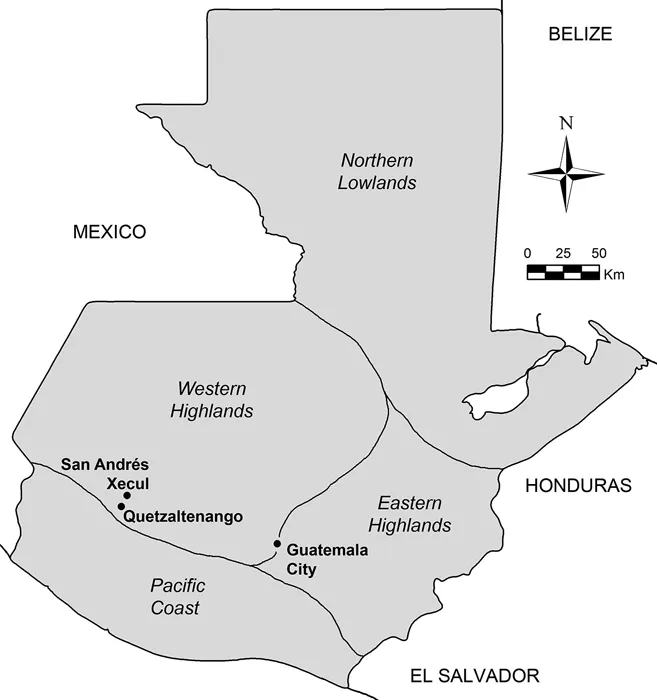

San Andrés Xecul is the smallest municipality in the Department of Totonicapán, with a total area of 17 km2, including arable and nonarable land. The center is 2,435 m above sea level, and the climate is cold by Guatemalan standards. Xecul borders San Cristóbal Totonicapán on the north and east, Olintepeque and Salcajá on the south, and San Francisco la Unión on the west (figure 1.1). Estimates of the town’s population vary considerably, though it has grown rapidly in recent years: from 25,967 in 2004 to 35,203 in 2012 (INE 2008: 3; 2013: 73). According to a census conducted in 2001 by the Spanish NGO Cooperación Española, which I used as a basis for a general survey of the town, as noted in the previous chapter, the population of Xecul’s urban center was a little under 4,000 (Vásquez Hernández 2002), though a study in 2008 estimated an urban population of over 7,000 (Mazariegos Vásquez 2009). Access between the center and the town’s four rural aldeas can be somewhat difficult: three of these are situated on the plains above the urban center, which itself is settled in a cleft of eastern and southern extensions of the Sierra Madre (figure 1.2). The painter Carmen Pettersen (1976: 52) described Xecul as bordering “a beautiful, rich, flat valley of deep soil and crystal clear streams,” but in truth the town center itself is poorly irrigated: there are no significant streams, crystal clear or otherwise, that service the urban population, and access to potable water (which is obtained by means of mechanical pumps accessing groundwater) is limited. During my principal period of fieldwork, homes typically enjoyed at most a few hours of running water each day, an issue that remains a key local concern (Mazariegos Vásquez 2009).

History of Xecul

Xecul has a long human history stretching back to the late Postclassic period at least, though the details of its past have yet to be thoroughly investigated. In 1944, the archaeologist Edwin Shook (1944) visited the town as part of an archaeological survey of the region he was conducting, noting in his field diary that the two mounds in the plains northeast of the town center, known as Pacajá Grande and Chico (used currently as Maya altars), are certainly prehispanic in origin. While he did not provide a date for these structures, given their undefended location it is possible that they date from the Classic period, as Postclassic sites are conventually understood to exhibit more defensive features (Borgstede and Mathieu 2007). Xecul’s Postclassic history is somewhat more clear, insofar as the town is mentioned in early sources as one of the towns conquered by the K’iche’ state centered at Utatlán (near present-day Santa Cruz del Quiché).1 In the Título de la Casa Ixquin-Nehaib, Señora del Territorio de Otzoya, collected by Adrian Recinos (1957), and referred to elsewhere by Robert Carmack (1973) as the Título Nijaib I, mention is made of Xecul as a Mam-controlled town that was conquered by the K’iche’—particularly the Nijaib lineage—likely during the reign of Kukumatz (approximately 1375–1425 CE), the first K’iche’ ruler who made important territorial expansions (Carmack 1995). The town was probably under the jurisdiction of Utatlán lords from Quetzaltenango, and thus part of the periphery of the K’iche’ state. Although Xeculenses gloss the name of their town as xe k’ul, which they translate as “below the blankets”—a term that also resonates in the mythology concerning the origins of the place, as I consider in chapter 2—in Mam the same term means “below the mountain top,” which might suggest a more straightforward geographical toponym, indirectly referencing a pre-K’iche’ history. The only other early documentary source treating Xecul comes from Francisco Fuentes y Guzmán’s Recordación Florida, written in the late seventeenth century and referencing a document called the Título Xecul Ajpop Quejam, which cites Don Juan Macario as Xecul’s prehispanic ruler and offers a K’iche’ account of the battle between Tecún Umán and Pedro de Alvarado, including preparations for war (Carmack 1973: 73–74).2

Despite its role in pre- and post-Conquest history, Xecul does not appear to have been settled extensively until the first centuries of the Colonial period. There are some scattered references to the town in documents in the National Archives in Guatemala City, which treat land disputes and petitions to the Colonial authorities in the eighteenth century. In a compendium of land documents from 1860 (which is archived in Xecul) collated and transcribed by a notary of Guatemala’s high court, some of the earlier history of the town is described. According to this source, by the end of the seventeenth century, migrants from neighboring San Cristóbal, who had earlier taken up lands in Xecul, sought to have their title recognized, as conflicts had erupted between these towns as well as Olintepeque. Xecul is thus considered an outgrowth from San Cristóbal, as noted in an entry from the eighth of February, 1698, which cites some 400 tributaries in Xecul, descended from residents of San Cristóbal, who in the absence of legal title simply began to act like a separate municipality, establishing such telling features of local autonomy as the now famous church.3 The population rose gradually through the Colonial period, with approximately 1,300 Xeculenses reported in 1818 (Pollack 2008, 233). Land struggles continued through the Colonial and into the Republican periods, for the most part against San Cristóbal, and later against Olintepeque.4 Xecul likewise played an active role in some of the important events surrounding Guatemalan independence, including participation in the 1820 rebellion led by Lucas Aguilar and Atanasio Tzul, which was centered in the departmental capital of San Miguel Totonicapán. Some Xeculenses actively supported the rebellion and served as guards for Tzul and Aguilar (Contreras R. 1968; McCreery 1989; Bricker 1981; Martínez Peláez 1985; Pollack 2008). Long a fitful annex to San Cristóbal, the town achieved status as a separate municipality in 1858.

It seems that the first extensive inroads of modernity into indigenous communities like Xecul (at least as related to the incursion of specific forms of state-sponsored capitalism) accompanied the Guatemalan state’s political and economic transformation toward the end of the nineteenth century as developed through a series of liberal dictatorships. The election of coffee as the resource to transform the country into a thriving, modern, and progressive nation had a direct but varied and complex effect upon indigenous communities (Handy 1994: 8–13). As a series of forced labor laws were enacted, communities were obliged to come up with often impossibly large numbers of workers to travel to the coastal plantations for various stretches of time (McCreery 1994). In Xecul, as reflected in documents in the town’s archives, community authorities found themselves obliged to round up and deliver large numbers of their townsfolk for very disagreeable work as mozos (forced laborers) in distant places—a responsibility the municipalidad clearly did not relish.5 It appears that as the targets of mandamientos (labor corvées) found their local authorities increasingly unable to protect their interests, many sought protection elsewhere—often in the person of a Ladino boss or patrón, who could provide a range of labor opportunities (not just agricultural) and who in some cases lived closer to their hometown, reducing the need for seasonal migration to coastal plantations.

By the turn of the twentieth century, while alcaldes in Xecul were under considerable pressure from their political overseers (and were periodically jailed for failing to deliver required numbers of mozos to coastal plantations), local administrations were nonetheless spending more money than ever before, inaugurating a series of impressive public works. More cash was entering the town, and the leadership found ways dispose of as much of this as they could locally—before the regional governments could claim it, through various taxes or “loans” that commonly were never repaid—through improvements to infrastructure, increased spending on education and secular patriotic celebrations, as well as increased expenses of bureaucracy.6 All of this occurred during a period when national, regional, and local governments were becoming increasingly integrated, and a “procedural culture” as Watanabe (2001) calls it, was being worked out. This implies that much of the augmented strength and authority of local communities was directly tied to at least a tacit acceptance of broader national political ideologies and institutions.7

In many predominantly indigenous communities, this period of liberal dictatorships—through to the revolutionary interlude beginning in 1944—also saw a more direct assault on local political autonomy, as Ladinos gained control of local administrations (Handy 1994: 11–12; McCreery 1994: 261–264). Xecul, however, managed to maintain an indigenous-dominated administration more or less through its entire history. Up until the years of Jorge Ubico’s dictatorship, even the position of secretary tended to be held exclusively by literate indigenous men. Although Ladino secretaries were often employed from the mid-1930s through the revolutionary period, by the mid-1950s indigenous Xeculenses again resumed control of this position. It is worth noting that even the position of intendente—established by Ubico ostensibly to replace locally elected alcaldes with direct appointees from outside the community (Carmack 1995: 192–193; McCreery 1994: 311)—was held by local Xeculenses, including sitting and...