- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Reshaping the World is a nuanced exploration of the plurality, complexity, and adaptability of Precolumbian and colonial-era Mesoamerican cosmological models and the ways in which anthropologists and historians have used colonial and indigenous texts to understand these models in the past. Since the early twentieth century, it has been popularly accepted that the Precolumbian Mesoamerican cosmological model comprised nine fixed layers of underworld and thirteen fixed layers of heavens. This layered model, which bears a close structural resemblance to a number of Eurasian cosmological models, derived in large part from scholars' reliance on colonial texts, such as the post–Spanish Conquest Codex Vaticanus A and Florentine Codex.

By reanalyzing and recontextualizing both indigenous and colonial texts and imagery in nine case studies examining Maya, Zapotec, Nahua, and Huichol cultures, the contributors discuss and challenge the commonly accepted notion that the cosmos was a static structure of superimposed levels unrelated to and unaffected by historical events and human actions. Instead, Mesoamerican cosmology consisted of a multitude of cosmographic repertoires that operated simultaneously as a result of historical circumstances and regional variations. These spaces were, and are, dynamic elements shaped, defined, and redefined throughout the course of human history. Indigenous cosmographies could be subdivided and organized in complex and diverse arrangements—as components in a dynamic interplay, which cannot be adequately understood if the cosmological discourse is reduced to a superposition of nine and thirteen levels.

Unlike previous studies, which focus on the reconstruction of a pan-Mesoamerican cosmological model, Reshaping the World shows how the movement of people, ideas, and objects in New Spain and neighboring regions produced a deep reconfiguration of Prehispanic cosmological and social structures, enriching them with new conceptions of space and time. The volume exposes the reciprocal influences of Mesoamerican and European theologies during the colonial era, offering expansive new ways of understanding Mesoamerican models of the cosmos.

Contributors:

Sergio Botta, Ana Díaz, Kerry Hull, Katarzyna Mikulska, Johannes Neurath, Jesper Nielsen, Toke Sellner Reunert†, David Tavárez, Alexander Tokovinine, Gabrielle Vail

By reanalyzing and recontextualizing both indigenous and colonial texts and imagery in nine case studies examining Maya, Zapotec, Nahua, and Huichol cultures, the contributors discuss and challenge the commonly accepted notion that the cosmos was a static structure of superimposed levels unrelated to and unaffected by historical events and human actions. Instead, Mesoamerican cosmology consisted of a multitude of cosmographic repertoires that operated simultaneously as a result of historical circumstances and regional variations. These spaces were, and are, dynamic elements shaped, defined, and redefined throughout the course of human history. Indigenous cosmographies could be subdivided and organized in complex and diverse arrangements—as components in a dynamic interplay, which cannot be adequately understood if the cosmological discourse is reduced to a superposition of nine and thirteen levels.

Unlike previous studies, which focus on the reconstruction of a pan-Mesoamerican cosmological model, Reshaping the World shows how the movement of people, ideas, and objects in New Spain and neighboring regions produced a deep reconfiguration of Prehispanic cosmological and social structures, enriching them with new conceptions of space and time. The volume exposes the reciprocal influences of Mesoamerican and European theologies during the colonial era, offering expansive new ways of understanding Mesoamerican models of the cosmos.

Contributors:

Sergio Botta, Ana Díaz, Kerry Hull, Katarzyna Mikulska, Johannes Neurath, Jesper Nielsen, Toke Sellner Reunert†, David Tavárez, Alexander Tokovinine, Gabrielle Vail

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Reshaping the World by Ana Díaz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University Press of ColoradoYear

2020Print ISBN

9781646420056, 9781607329435eBook ISBN

9781607329534Part I

Recognition

On Describing Others’ Worlds

1

Colliding Universes

A Reconsideration of the Structure of the Precolumbian Mesoamerican Cosmos

Jesper Nielsen and Toke Sellner Reunert

The same Indian collaborators who helped Sahagún to Indianize the Christian message were responsible for Christianizing the Indian past. (Escalante 2003, 186)

A recurring methodological discussion in Mesoamerican and Andean research has centered on the use of ethnohistorical or ethnographic analogies or the “direct historical approach” (e.g., Kubler 1973; Willey 1973; Nicholson 1976; Jansen 1988; Quilter 1996). Although the authors of this chapter find this approach both inevitable and productive, and while we do not believe that potential disjunctions in form and meaning should cause us to exclude the use of analogies, the present study emphasizes how important it is to investigate and trace the development of any cultural element, belief or otherwise, in time and space with extreme care. We suggest that a generalization has taken place regarding the idea of a multilayered Mesoamerican universe, showing that this cosmic structure has been inferred primarily from postcolumbian central Mexican sources and not from precolumbian evidence such as Maya hieroglyphic texts or iconography. Second, we elaborate on our already-published hypothesis that the notion of a multilayered universe (beyond the three tiers of heaven, earth, and underworld) was not a Mesoamerican concept in the first place, but was only introduced into the area in the sixteenth century, and that it ultimately derives from European visions of the cosmos (Nielsen and Sellner Reunert 2009; see also recent contributions on the subject by Díaz 2009; 2011, 158–200; 2015; Díaz and Alcántara 2011). Our point here is not to say that this multilayered cosmology, which in our view was a result of European influence, was necessarily caused by a direct influence from the writings of Dante. The influence may very well have been indirect, since the Dantean worldview was widely accepted in most of Europe at the time of the conquest. In this chapter we further examine under which circumstances and by whom the sixteenth-century sources on Mesoamerican religion and cosmography were composed. We begin, however, with a look at two sources that present different yet clearly related visions of the Mesoamerican cosmos.

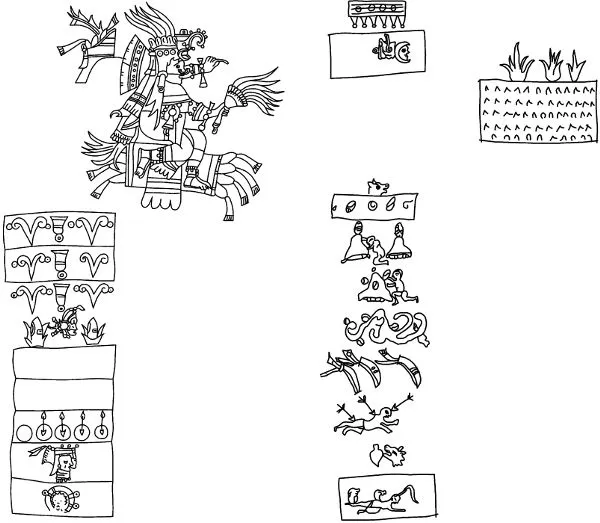

Layers or Regions: The Topography of the Otherworld

In the mid-sixteenth-century K’iche’ epic, the Popol Vuh, we can read the narrative of the Hero Twins and their experiences in six houses or caves in Xib’alb’a, the dreadful underworld. In each of these houses the twins have to face and deal with a specific test or danger. Thus, the second house is called “Blade House” and is filled with sharp cutting blades and the fourth house is the “House of Jaguars” (Christenson 2003, 163–174). In the description it would appear that all houses are arranged on the same level, that is, the houses are all situated at “ground level” in Xib’alb’a. If we compare the houses and their characteristics to the layers of the Aztec underworld according to the Codex Vaticanus A (dated to between 1566 and 1589; see Glass and Robertson 1975, 186), we find some significant similarities between the houses of the Popol Vuh and the correspondent layers in Vaticanus A (Miller and Taube 1993, 177–178). In the Codex Vaticanus A, the first layer beneath the earth is called Apanohuayan (“Water Passage”), while the second is named Tepetl Imonamiquiyan (“Where the Hills Clash Together”) (Nicholson 1971, 406–408, fig. 7, table 2) (also see figure 1.1). In the Popol Vuh the Hero Twins begin their journey to Xib’alb’a by passing through great river canyons, which can indeed be described as narrow spaces where the rocks come together, and they cross the big rivers of Pus and Blood (Christenson 2003, 160). In Vaticanus A we also encounter layers named Itztepetl (“Obsidian Knife Hill”), Itzehecayan (“Place of the Obsidian-Bladed Wind”), and Temiminaloyan (“Where Someone Is Shot with Arrows”), which all can be compared to the “Blade House” in the K’iche’ epic in the sense that they are places where blades inflict pain on humans. The “Place of the Obsidian-Bladed Wind” finds its parallel in the “House of Cold” where the Hero Twins are met by a constant storm of hail (Christenson 2003, 169). The Aztecs called the eighth layer of the underworld Teyollocualoyan (“Where Someone’s Heart Is Eaten”) and this is illustrated by a coyote or jaguar devouring a human heart. The obvious K’iche’ parallel to this is the “House of Jaguars” and the house of man-eating bats. It would thus seem that while the K’iche’ highland Maya associated these tests and frightening beings with a group of horizontally arranged houses, the contemporaneous Aztecs identified them with a series of vertically arranged layers.

Is this simply an example of two alternative Mesoamerican concepts? Or can the difference best be explained by other historical developments and cultural mechanisms? As already indicated, we show that it cannot be verified that the vertical multilayered structure is an indigenous precolumbian model of the cosmos. All known sources that make clear references to such a multilayered cosmological structure are from the central Mexican highlands and all are of postcolumbian origin. We therefore suggest that the concept of a multilayered universe came only with the Spanish intruders—more specifically the Franciscans and Dominicans—and with what we here call a Dantean worldview with nine layers in both heaven and the underworld. Yet today, the idea of a multilayered Mesoamerican cosmos has become extremely widespread and accepted in the field; we briefly discuss how this particular image of the universe has been described and applied in the scholarly literature on the Aztecs and the ancient Maya.

Previous Research and the Consensus on Mesoamerican Cosmology

It is fair to say that most Mesoamericanists of today have been taught along the same lines when it comes to the worldview and cosmology of the ancient Maya and Aztecs. The majority of textbooks available describe how the spheres of the heaven and the underworld were divided into a number of layers (the exact numbers varying depending on the source used). Susan Toby Evans states: “To Mesoamericans, the cosmos had multiple levels. The Aztecs saw nine levels of the underworld and 13 of the upper world, with earth as the first level of each” (Toby 2004, 292; see also Sharer and Traxler 2006, 730–732; Wagner 2006, 286–287; Stuart 2011, 87). Mary Miller and Karl Taube note that “at the time of the Conquest, most Central Mexican people believed in the cosmographical scheme of nine levels of the Underworld, with 13 levels of upper world,” and they refer to the Codex Vaticanus A as the source “where the 9–13 scheme receives its most explicit and ample representation.” However, they also add that “the Maya certainly perceived layers of both Underworld and upper world but the notion of nine levels of the Underworld is not specific or universal for the Maya, nor is it for either the Mixtecs or the Zapotecs” (Miller and Taube 1993, 177–178). Miller and Taube’s note of caution is important, as it turns out that it is almost exclusively Codex Vaticanus A that is referred to, if any source is mentioned at all, in the broad synthesizing statements of a Mesoamerican multilayered cosmography.

Figure 1.1. The multilayered structure of the Aztec cosmos as it is represented in the Codex Vaticanus A (fols. 1v–2r), sixteenth century. (Drawing by Victor Medina.) The drawing visualizes the idea of a layered cosmos, with ten heavenly layers to the left and the remaining three appearing to the right. Below, to the right, are the nine levels of the underworld. The uppermost level of the sky is represented by the deity Tonacatecuhtli, an aged god of creation and as such an ideal parallel to the Christian god.

If we want to understand how the Vaticanus A image came to dominate scholars’ ideas and perception of Mesoamerican cosmography we need to begin with Eduard Seler, the “dean” of Mesoamerican studies. It was Seler (1849–1922) who presented the first lengthy discussion of central Mexican cosmography, including the belief in the existence of several layers in the heaven and in the underworld. In his brilliant analysis Seler was careful to explain that a variety of ways to perceive the layout of the underworld seems to have existed (Seler 1996, 3–23). For example, he wrote that “in the same way as the earth, this flat, two-dimensional shield [of the underworld] was cut up into nine regions corresponding to the four cardinal directions. Thus, the underworld was divided into nine regions” (Seler 1996, 9). He also noted that some texts speak of nine heavens rather than thirteen (Seler 1996, 9, 17–19), and in describing the underworld and heavenly layers depicted in the Codex Vaticanus A scene in great detail, he pointed out that “the meaning of the several heavenly spheres is not as clear as those of the underworld. The task of filling in the thirteen of them has apparently bothered the old philosophers even more than that of characterizing the nine hells completely” (Seler 1996, 15). Furthermore, Seler stressed that at certain points the illustration seems to have been influenced by a European style—in the way the moon is represented, for example (Seler 1996, 15). Despite Seler’s nuanced presentation of the potentially very different arrangements of the underworld according to local Aztec schools and traditions, the Vaticanus A scheme has since become the standard way of understanding and interpreting ancient central Mexican cosmography (e.g., León-Portilla 1956, 122–128; López Austin 1988, I, 52–61; 1997). Apparently, the image of a clear and recognizable vertical structure of the universe was favored to other contrasting and unillustrated versions. In 1961 Walter Krickeberg, another well-known German Americanist, wrote of the cosmology of the Postclassic cultures:

According to the most ancient version, the earth is a flat disc sandwiched between the bases of two immense step-pyramids . . . The stream which flows round the earth and round the bases of the two pyramids is called Chicunauhapan, ‘nine stream’, because there are nine heavens and nine underworlds. The Aztecs replaced this stepped universe with a layered one and increased the number of heavens to thirteen. In the step hypothesis the highest heaven and the deepest hell lie at the apex of each pyramid; in the horizontal layer hypothesis the two constitute the top and bottom layers. The older idea is the more logical, it fits better with the idea that the sun climbs and descends a pyramid each day (and does the reverse every night) . . . The Aztecs regarded each of the thirteen upper layers as the seat of a particular deity or natural phenomenon, and each of the nine nether layers as a region in which a succession of terrors awaited the sun and the souls of the dead. (Krickeberg et al. 1968, 39–40)

A problem with Krickeberg’s presentation is the lack of references to sources. It is unclear what “the most ancient version” is, and Krickeberg’s reasoning that the step-version was replaced by a layer-version by the Aztecs is equally problematic. What can be concluded, however, is that his analysis contributed to establish the generalized and unquesti...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of figures

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Rethinking the Mesoamerican Cosmos

- Part I. Recognition: On Describing Others’ Worlds

- Part II. Inventiveness: Reshaping Experience in Colonial Cosmologies

- Part III. Complexity: Breaking Paradigms on Cosmological Conceptions

- About the Authors

- Index