eBook - ePub

Risk Communication and Miscommunication

Case Studies in Science, Technology, Engineering, Government, and Community Organizations

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Risk Communication and Miscommunication

Case Studies in Science, Technology, Engineering, Government, and Community Organizations

About this book

Effective communication can help prevent or minimize damage from environmental disasters. In Risk Communication and Miscommunication, Carolyn Boiarsky teaches students, technical writers, public affairs officers, engineers, scientists, and governmental officials the writing and communication skills necessary for dealing with environmental and technological problems that could lead to major crises.

Drawing from research in rhetoric, linguistics, technical communication, educational psychology, and web design, Boiarsky provides a new way to look at risk communication. She shows how failing to consider the readers' needs or the rhetorical context in which one writes can be catastrophic and how anticipating those needs can enhance effectiveness and prevent disaster. She examines the communications and miscommunications of original e-mails, memos, and presentations about various environmental disasters, including the Columbia space shuttle explosion and the BP/Deepwater Horizon oil rig explosion, and successes, such as the Enbridge pipeline expansion and the opening of the Mississippi Spillway, and offers recommendations for effective communication.

Taking into account the growing need to communicate complex and often controversial issues across vast geographic and cultural spaces with an ever-expanding array of electronic media, Risk Communication and Miscommunication provides strategies for clear communication of data, ideas, and procedures to varied audiences to prevent or minimize damage from environmental incidents.

Drawing from research in rhetoric, linguistics, technical communication, educational psychology, and web design, Boiarsky provides a new way to look at risk communication. She shows how failing to consider the readers' needs or the rhetorical context in which one writes can be catastrophic and how anticipating those needs can enhance effectiveness and prevent disaster. She examines the communications and miscommunications of original e-mails, memos, and presentations about various environmental disasters, including the Columbia space shuttle explosion and the BP/Deepwater Horizon oil rig explosion, and successes, such as the Enbridge pipeline expansion and the opening of the Mississippi Spillway, and offers recommendations for effective communication.

Taking into account the growing need to communicate complex and often controversial issues across vast geographic and cultural spaces with an ever-expanding array of electronic media, Risk Communication and Miscommunication provides strategies for clear communication of data, ideas, and procedures to varied audiences to prevent or minimize damage from environmental incidents.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Risk Communication and Miscommunication by Carolyn Boiarsky in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Creative Writing. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Writing and Reading in the Context of the Environmental Sciences

A Case Study of the Chicago Flood

Introduction

The Chicago flood of 1992 was a man-made environmental disaster,1 caused by city officials failing to plug a leak in a wall, rather than a natural disaster, such as the lower Mississippi River flood of 2011,2 caused by the natural forces of melting snow to the north in winter and excessive spring rain. As with so many environmental disasters, the Chicago flood might have been averted had a memo written earlier been heeded.3 The information Chicago engineers were expected to provide their managers in a request to repair the tunnel leak under the Kinzie Street Bridge in 1992—description of problem, cause, corrective action and estimated cost—is the same today as it was then. The difference is that today the request would have been sent electronically as an e-mail rather than through interoffice mail as a memorandum.

The Chicago Flood

On Monday, April 13, 1992, downtown Chicago came to a standstill. The Chicago River was flooding freight tunnels that had been dug underneath the city in the early part of the twentieth century. Water was seeping into the basements of office buildings in the city’s financial district, with its stock exchange, commodities market, and Federal Reserve, and into the upscale retail area, where department stores such as Marshall Field’s (now Macy’s), Burberry, and Neiman Marcus are located. All buildings in the area were evacuated and traffic halted. Downtown Chicago became a ghost town for three days. The city took weeks to pump all the water out. The cost in closed business and ruined inventory ran to approximately $1.25 billion.

The cause of the flood was a leak in the wall of one of the tunnels abutting the river. Several weeks earlier Louis Koncza, the chief engineer for the Bureau of Bridges in the city’s Department of Transportation (DOT), had sent a memo to John LaPlante, acting DOT Commissioner, notifying him of the leak and requesting permission to repair the walls. But the wall wasn’t repaired before the leak became a flood. Miscommunication between Koncza and LaPlante was one of the reasons.

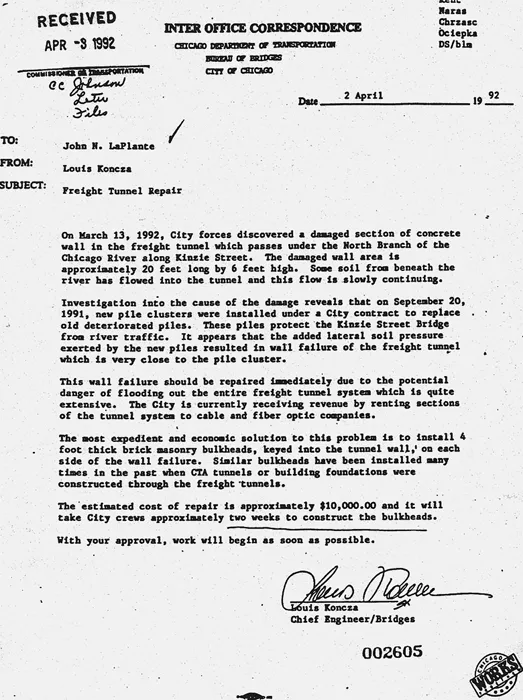

Beneath the city of Chicago lies a labyrinth of tunnels that were created at the beginning of the twentieth century. The tunnels allowed small train cars to carry coal from the barges that came down Lake Michigan to the basements of the city’s buildings above. With the change from coal to oil and gas in the latter part of the twentieth century, the city began to lease these tunnels to cable companies for stringing their cables. In January, four months before the flood, a cable company employee went into the tunnel near the Kinzie Street Bridge to study the situation prior to the company’s installing the wire. The employee found water and soil leaking into the tunnel and notified his company, which, in turn, notified the city. A city engineer was sent to investigate but couldn’t find a parking place. It took over a month before another employee was sent to check out the report. This time he found a parking place. However, by now the small leak had become a large leak, and the employee found so much damage to the wall that he felt it was unsafe to enter the tunnel. He took photographs and returned. After several meetings to determine what should be done and to estimate the cost for the repair, Louis Koncza was charged with writing a memorandum to the manager of his division, John LaPlante, requesting permission to repair the tunnel (Figure 1.1).4

Figure 1.1. Koncza’s memo to LaPlante

The memo was typed on a form for interoffice correspondence that included in the upper right-hand corner the names of the people other than Koncza to whom documents in the DOT were routinely distributed. These people were often involved with some aspect of a project. In this case, one of the men, Ociepka, had been the project manager for the installation of new pile clusters around the Kinzie Street Bridge, where the leak had begun. Apparently, during the installation, one of the piles had hit the tunnel wall, puncturing it. Another reader, Chrasc, worked under Koncza as his coordinating engineer and would be responsible for coordinating the repair project. Koncza penciled in at the upper left-hand corner the names of three additional people who needed to be informed of the repair work for the leak. Many of these people were eventually fired by then-mayor Richard Daley, Sr.

Koncza, who was busy and had several other problems demanding attention, did not spend much time planning the memo. Instead he wrote it using the same organizational structure that he had used in writing many previous memoranda. He was very much aware of the economic aspect of the tunnel, which brought rental fees to the city, and alluded to this, implying that if the tunnel was not fixed, the city might lose its fees. He did not take much time to read it over and make revisions, other than checking that the facts were correct and then proofreading it for grammatical or spelling errors. On April 2 Koncza sent the memo through interoffice mail to his supervisor rather than delivering it in person as was the convention for matters requiring immediate action.

LaPlante received the memorandum along with a large batch of other interoffice mail the following day, April 3. He constantly received memos describing construction problems and requesting approval to have them repaired. Because this one had been transmitted by interoffice mail rather than in person, it did not appear different from the others.5

When LaPlante received the memo in the pile of mail delivered to his desk that Friday afternoon, he simply gathered it along with the entire pile and took it home. On Sunday afternoon, he read through the stack of memos, including the one on the Kinzie Street Bridge.

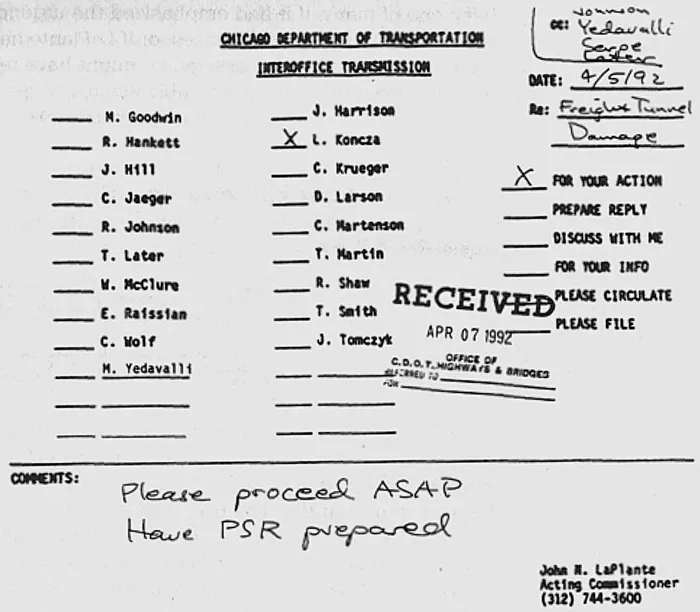

LaPlante had only recently been appointed to the position in an acting capacity. He was not an engineer but a financial manager. He had little knowledge about the problem discussed in the memo; he wasn’t even sure where the Kinzie Street Bridge was. Having no secretary or typewriter available (this was BC [Before Computers]), he handwrote his response on one of his memorandum forms, approving the repair. Recognizing that the mayor was up for reelection (the political context), he recommended that the repair job be put up for bid. (A PSR [project specification report] is a form for putting out a bid.) He also penciled in the names of several other readers who needed to be kept informed of the project (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2. Approval for a PSR

Returning to work on Monday, LaPlante placed the memo in interoffice mail. It was delivered on Thursday, as the stamp in the upper left-hand corner indicates. It took three more days for Koncza to respond to LaPlante’s orders and send a memo requesting that the PSR be processed.

The PSR was prepared and put out for bid. Two bids came in by April 10. Both were over $70,000, approximately, $60,000 over t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- How to Read This Book

- Introduction

- Chapter 1. Writing and Reading in the Context of the Environmental Sciences: A Case Study of the Chicago Flood

- Chapter 2. Effective Discourse Strategies: A Case Study of the 2011 Mississippi Flood

- Chapter 3. Effective Persuasive Strategies: Cheap, Available Coal Power vs. a Clean Environment

- Chapter 4. Communicating with Electronic Media: Case Studies in the Columbia Shuttle Breakup and the BP/Horizon Oil Rig Explosion

- Chapter 5. Communicating with PowerPoint: The Army, NASA, and the Enbridge Pipeline

- Bibliography

- Websites with Background and Additional Information

- Index