eBook - ePub

Island of Grass

About this book

Island of Grass tells the story of the Cathy Fromme Prairie Natural Area, a 240-acre preserve surrounded by housing developments in Fort Collins, Colorado. This small grassland is a remnant of the once-vast prairies of the West that early European explorers and settlers described as seas of grass.Agricultural land use and urban expansion during the past two centuries have fragmented and altered these prairies. All that remains today are small islands. These remnants cannot support some of the larger animals that once roamed the prairie, but they continue to support a diverse array of plants and animals and can still teach us much about grassland ecology. Through her examinations of daily changes during walks across the Fromme Prairie over the course of a year, Ellen Wohl explores one of the more neglected ecosystems in North America, describing the geology, soils, climate, ecology, and natural history of the area, as well as providing glimpses into the lives of the plants, animals, and microbes inhabiting this landscape. Although small in size, pieces of preserved shortgrass prairie like the Cathy Fromme Prairie Natural Area are rich, diverse, and accessible natural environments deserving of awareness, appreciation, and protection. Anyone concerned with the ecology and conservation of grasslands in general, the ecology and conservation of open space in urban areas, or the natural history of Colorado will be interested in this book.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Island of Grass by Ellen E. Wohl in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9781607320074Subtopic

EcologyPART TWO

THE FROMME PRAIRIE

GRASSROOTS

A child said “What is the grass?” fetching it to me with full hands, How could I answer the child? I do not know what it is any more than he.

—WALT WHITMAN, “SONG OF MYSELF”*

At the base of the Colorado Front Range lies a tiny patch of undulating grassland that occupies the boundary between two of the continent’s enormous physiographic regions: the wide-spreading interior plains to the east and the broad band of the Rockies to the west. Geology, topography, climate, and ecological communities differ dramatically east and west of this point on Earth. Eastward there is no boundary but the distant meeting of land and sky. Westward the first row of the foothills forms a solid dark line on the western horizon each evening. This line marks the western limits of the grassland. The land rises steeply into rocky slopes on which tough mountain mahogany bushes and gnarled ponderosa pine trees start to displace the grasses. Further west, beyond the first row of foothills, lodgepole pines and spruce and fir replace the ponderosas and eventually give way to alpine meadows thousands of feet higher in elevation than the prairie.

View west, across yucca on a hill slope at the Fromme Prairie to the forested foothills.

At the base of the foothills, flat-topped old stream terraces running east-west corrugate the land. Gently folded swales divide the terraces, collecting the meager rainfall and snowmelt that reach this dry portion of central Colorado. The water moves slowly, pooling in a cattail marsh, then seeping onward again to join the shallow course of Fossil Creek. The patch of prairie spreads toward the remaining horizons, its borders trimmed by rows of houses.

There is just sufficient prairie—1,082 acres—to sense how the land once looked. Humans set this prairie aside from agriculture and houses for the benefit of both the life within and the people who live on its borders. Although small, parts of its story reflect that of all the shortgrass prairie once covering the western Great Plains. This story starts at the grassroots; continues through the bustle and brevity of the life of a grasshopper, a prairie dog, and a coyote; and ends on the wings of a hawk riding atmospheric currents that bring the greater world to the prairie. So much happens during the course of a year on this small island of grass that thick chronicles could be written, but this brief narrative provides a glimpse into a year, just as the small prairie island provides a glimpse into the once vast sea of grass.

All winter the patch of prairie remains muted, the grasses having died back to straw-colored stubble punctuated only by an occasional yucca or rabbitbrush. Bitterly cold winter winds pit the stubble with hard-driven snow, but the snow seldom lingers. The dry winds sublimate the white crystals or mold them into small drifts in the lee of the bunchgrasses, and within a day or two they are gone. Most creatures are out of sight, but the prairie dogs remain active, their squeaks of alarm sounding when a cruising raptor passes by. Otherwise the landscape waits quietly.

Spring arrives on gusting chinook winds that warm the air, only to be interrupted by arctic winds that can drop the temperature thirty degrees in a few hours. But the warmth gradually wins out as the days grow longer. The entire prairie stirs from its winter of dormancy.

The prairie awakening begins each spring with the greening of the grasses. Everything centers on the grasses. Soil fungi and earthworms live on bits of root and shed plant litter. Caterpillars and grasshoppers eat stem and leaf aboveground. Western meadowlarks and prairie falcons and thirteen-lined ground squirrels pursue the insects, and coyotes and golden eagles swallow rabbits, rodents, and smaller birds with eager appetite.

As the days grow longer during March and April, explosions of green burst across the prairie. Big bluestem surges up from nine-foot-deep roots into gangly seed stalks well over three feet tall. On loose sandy slopes, sand reedgrass sends up coarse stalks to catch the wind with a hiss. Native purple threeawn and invasive prairie threeawn grow slender leaves tapering to a fine point from which narrow, wiry seeds each hold three bristles like long antennae.

The greening grasses survived the lean winter season, when the carbohydrate reserves stored in their roots reach their lowest levels. The plant draws on these reserves throughout the autumn and winter, and if prairie dogs or soil microorganisms eat the portions of the plant that store carbohydrates or if the plant did not store enough sugars and starch in its tissues during the growing season, it will die. Spring regrowth takes a lot of energy, but the payoff comes in new photosynthetic tissue that can replenish the carbohydrate reserves once production exceeds the plant’s immediate needs.

The prairie does not green all at once. Patches of new growth appear on the slopes while the lowlands along the small channels remain brown. The early blooms appear. Elegant white clusters of sand lily spring up overnight, and wild parsley blossoms in patches of sunshine yellow. The sepia tones of the winter prairie give way to a broader spectrum of color.

Blue grama is one of the most abundant grass species here. Its slender leaves and seed stalks curl like eyelashes, making the plant appear tenuous on this prairie of intense sunlight and dessicating winds. Even the species name, gracilis, reflects the plant’s fragile appearance. But blue grama is a native here, a C4 plant with metabolic pathways specially adapted to the prairie’s warmth, intense sunlight, and periods of water stress. Unlike many plants, it can continue to photosynthesize even when stressed by low moisture levels. The tenacious little blue grama reaches its period of greatest activity in mid- to late summer when air temperatures on the prairie hover between 90° and 100°F at midday.

Sand lily in bloom, Fromme Prairie. The white petals grow on short stalks only a couple of inches above the ground.

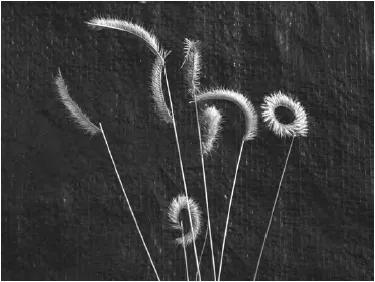

Seed heads of blue grama grass.

Some plants avoid dehydration by accumulating water in spongy tissues. Others extend their roots deep into the soil profile until they reach subsurface water. Still others limit water loss from leaves by developing a thick, waxy surface layer or fine hairs that reduce air movement immediately at the leaf surface. Blue grama lacks spongy tissue and a thick leaf surface, and its roots do not extend far downward. Instead, blue grama relies on the ability of its basal stem close to the ground to resist drying. This, along with the roots, forms the vital center of the plant that remains alive during times of stress, and from this vital center new shoots and roots grow when conditions improve. The strength of this vital center increases as the plant ages and is able to store more carbohydrates against lean times.

Grasses appear deceptively simple at the surface—a few green blades, perhaps an inconspicuous flower, or, later, a more readily apparent seed head. This apparent simplicity belies the complex biochemical strategies that allow grasses to survive drought, fire, grazing, limited nutrients, even winter. Unlike animals, which stop growing when they reach maturity, plants continue to grow throughout their entire life span from special tissues in their roots and shoots. In blue grama, this tissue goes dormant during winter and resumes growth in the spring. Most years, some green growth at the leaf tips of blue grama is visible by the first or second week in April. This is the start of the seasonal race. The first leaf or two will mature and die by the end of June. Successive leaves grow longer, and the plant’s ability to produce carbohydrates depends on their growth. The longer leaves will reach about a third of their length by the end of May and two-thirds by the end of June. Leaf growth decreases in early July and becomes insignificant by mid-July, hence the race. Blue grama plants have only about three months to grow the photosynthetic surfaces they use to build carbohydrates before the plant above the lower portion of the stem close to the ground dies about mid-September.

Like other grasses, blue grama has two potential ways to reproduce. Asexual reproduction involves no new shuffling of the genetic material of two parent plants. Instead, a single parent sends out genetic copies of itself. Blue grama reproduces asexually by sending out lateral stems just below the ground surface. New shoots grow upward from these lateral stems so that a clump of blue grama grows outward. In a sense, this is a relatively safe way to reproduce because new shoots remain connected to the larger parent plant.

About one in ten of the blue grama shoots that remain dormant through the winter produces flowers for sexual reproduction. Some of these shoots do not flower until their third growing season so that they can store sufficient energy to grow larger and gain a competitive advantage over other shoots. Flowers start to appear at the end of June. Sexual reproduction is riskier because many seeds do not survive germination. Considering in detail the sequence of events needed for successful germination, it seems miraculous that any blue grama survive the first year. The longevity of adult blue grama plants offsets the high mortality of seedlings.

When a grass seed germinates, it first develops a primary root that grows downward from the seed and then additional lateral roots that branch slightly from the primary root below the seed. The primary root of blue grama is seldom longer than four inches. The first critical period for survival of blue grama seedlings occurs immediately, when the soil surface must remain moist for two to four days for seeds to germinate and initiate growth of the primary root. Because the primary root grows less than half an inch each day even under favorable conditions, the soil can dry almost as rapidly as the primary root is growing downward.

The second critical period comes about five to six weeks later, when the primary root begins to deteriorate and progressive downward drying of the soil can get close to the maximum depth of rooting. The plant’s ability to absorb water from the soil at this point is limited by the primary root’s maximum capacity for water uptake, as well as the soil moisture.

While the primary root grows downward, a seedling grows upward from the seed. The ability of the seed to produce tissues that force a way through the soil is fueled by the production of enzymes that alter the starch and protein stored in the seed into soluble sugars and amino acids the embryo and then the seedling use for growth. All of this is to no avail, however, if the seedling cannot obtain sufficient water.

A third critical period for blue grama seedlings can result from water stress even if the entire primary root is growing in moist soil. The primary root reaches the upper limit of its capacity to absorb water soon after the seedling emerges from the soil, imposing a limit on how much leaf tissue can be kept alive. When seedlings reach these limits, hot, dry winds can cause the seedling to die or reduce the area of green leaves because the rate of water loss from the leaves exceeds the rate of water uptake by the primary root.

The final critical period in the establishment of a blue grama seedling occurs when adventitious roots develop above the seed very close to the ground surface. Because the root system of most mature grass plants consists entirely of adventitious roots, survival of the seedling ultimately depends on its ability to develop those roots. A second moist period of two to four days is required anywhere from two to eight weeks after germination for adventitious roots to initiate growth. Although a blue grama seedling is very resistant to drought and can remain alive for long periods without growing, seedlings that do not develop adventitious roots do not survive the next winter. Yet because the adventitious roots lie less than an inch below the surface, where the soil is dry except during or immediately after a rain or snowmelt, many adventitious roots become dead stubs. Drying of the soil in mid–growing season causes the death of one- to two-thirds of newly formed adventitious roots. Blue grama plants can make up for this with massive root growth during times of moist soil near the end of the growing season.

Blue grama seedlings in effect gamble on the weather. Because temperatures lower than 59°F are inadequate for establishment of adventitious roots, seeds can germinate in early May, when soil temperatures are marginal for root growth but there is a greater chance of two or more consecutive wet days. Or seeds can germinate in midsummer, when soil temperatures are more favorable for seedling emergence and root growth but it becomes less likely that two or more consecutive wet days will occur. Ideal weather conditions for blue grama seed germination and establishment occur infrequently, and this, combined with competition for soil moisture from established adult plants, makes sexual reproduction by blue grama a rare event. This is why croplands that have lain fallow for sixty years at the Central Plains Experimental Range still have no blue grama growing on them.

As with other organisms, neighborhood matters for a blue grama plant struggling to survive its first year. The seedling’s immediate environment can determine whether sufficient moisture is available for adventitious roots to grow and survive. Minute variations in the topography of the soil surface, the presence of plant litter, and the presence of neighboring plants all influence the rate at which soil dries. Seedlings do better in the absence of neighboring adult blue grama plants that compete with them for soil moisture. Anything that creates limited gaps in blue grama communities can thus help new seedlings get established.

As the newly growing asexual shoots of blue grama and the shoots and flowers of other plants begin to appear across the Fromme Prairie in spring, the air takes on new life as well. Wind-ragged flocks of ducks pass overhead, black-headed scaups flashing white wing stripes and redheads showing more subdued gray stripes. The resident Canada geese fly back and forth in tight chevrons. Tiny broad-tailed hummingbirds whir by on their resolute flight to their summer range in the northern mountains. The resident winter raptors—rough-legged hawks, merlins, and bald eagles—catch the migratory urge and turn to the north. Coppery-breasted western bluebirds leave their winter supply of berries and flutter up into the mountains to feed on the insects buzzing in the newfound warmth. The summer residents arrive on the prairie, greeted by the vibrant song of the western meadowlarks that have remained throughout the year. The fluid spring melodies of the meadowlarks promise a richer life, carried on gusts of cold wind while the stirrings of spring are just beginning to drive green rivulets of life into the plants.

The restlessness of the spring air also stirs those who have wintered in the earth. Snakes emerge from their dens hungry for the boreal chorus frogs emerging from the mud of the wetlands. Red foxes and coyotes give birth to young who will eat many a prairie dog and meadow vole and ground squirrel, even as the small rodents give birth to their own young.

The prairie changes swiftly now from week to week. Stalks bearing creamy white flowers rise above the rapidly greening grasses, the beauty of the flowers betrayed by the name “death camas.” White flushes of silky locoweed appear. The lengthening hours of sunlight and the spring rains coax the shrubs and sedges and grasses into new sage-green and emerald growth, and the teeming microorganisms of the soil stir themselves into new cycles of activity as the grasses flourish.

Sagebrush, yucca, prickly pear cactus, and rabbitbrush dot the prairie. But the grasses dominate: ricegrass, needlegrass, bluestem, threeawn, grama, saltgrass, wheatgrass, mannagrass, junegrass, muhly, sacaton, dropseed, switchgrass, bluegrass, alkaligrass, indiangrass, cord-grass. More than fifty native species of grass and nearly twenty introduced species bend and twist in the winds that blow nearly constantly across the prairie. Deceptively delicate, the native plants of the shortgrass prairie are nonetheless tough survivors that adapt to dry seasons by curling their leaves and closing their stomata. They produce seeds that germinate in dry soil or that remain dormant until a wetter season sets them to sucking up nutrients and growing quickly.

Seed heads of buffalo grass.

Interspersed among the bunches of blue grama is buffalo grass, another native species adapted to the heat and drought. The tough little grass seldom grows more than half a foot tall, but it sends roots nearly six feet down, hiding its mass from the dessicating air and the grazing animals with which it evolved. Blue grama and buffalo grass are the two characteristic plant species that together define the geographic extent of the shortgrass prairie.

Buffalo grass creates a sod as its lateral stems grow across the ground an inch or two a day until they form a clump more than two feet across. Blue grama appears more contained on the Fromme Prairie, where grazing has not occurred for decades. Each plant forms a bunch separated by other plants or by bare ground. What appear to be separate plants may in fact all be part of one organism that can live at least forty years. A grass plant starts from growth units known as tillers connected to one another at the basal area of the stem. Some tillers produce only leaves; others produce a stem, seed head, roots, and leaves. Differentiation between these two potential pathways depends on environmental conditions. An individual plant can have more than a hundred live tillers. Tillers in the center die as the plant grows broader, until eventually the surface portion of the plant forms discrete clumps. These genetically identical clumps spread slowly, at ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright Page

- CONTENTS

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- THE GREATER CONTEXT

- THE FROMME PRAIRIE

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Glossary of Common and Scientific Names of Animals and Plants Described in the Text

- A Partial List of U.S. and Canadian Grassland Preserves

- Index

- Footnotes