1

Spring-to-Summer Celebration

Abundance and Redundancy

Every June since 1985, on a Saturday close to the summer solstice, a Midsummer pole has been raised on the lawn at Sealander Park, on the centennial farm established by Carl Sealander and still run by his grandson Dave. The park is a grassy oasis surrounded by Russian olive, cottonwood, and juniper trees among the sagebrush, lava beds, and irrigated fields of New Sweden, Idaho, just southwest of Idaho Falls. When I participated in the pole raising on June 23, 2001,1 we had a perfect day at Sealander Park: pleasantly warm, windless, and bright with sunshine. On the edges of the park, we early arrivals got to work, our first step unwinding twine to strip off last year’s dried greenery. Dave Sealander likes to leave the pole up throughout the year and bring it down the evening before or even the morning of the Midsummer gathering. In 2001, that happened precipitously—when one of the ropes securing the pole snapped in a windstorm a few weeks before. The pole toppled, worrying Dave and spurring him to design a new method for securing it. While the rest of us decorated and reassembled the pole, he spent the afternoon in his shop in the barn, welding a new cap for the top of the pole that would hold guy wires rather than rope.

We worked on through the afternoon: stripping the old materials, cutting fresh vegetation from areas along the park margins that needed pruning, gathering shasta daisies from a neighbor, braiding daisy chains, and wrapping the pole with the fresh greenery and flowers. Workers drifted in and out of the process, taking breaks for horse drawn wagon rides or conversations in the shade. On the wagon ride I joined, the riders sang rounds in English and German. Gradually more people arrived, including Dave Combs, accordianist in the group “Squeeze Play,” who strolled among the workers and spectators playing Nordic2 music and chatting. Dave Combs planned to leave the next day for Norway, where he and his family would be visiting relatives.

With Dave Sealander still busy in his shop, we carried the long mast to the site in the middle of the park where the pole would be raised. Those participants who had raised the pole before tried to remember how the pieces fit together. Where should the large rings be placed? The smaller ones? Even annual participants were puzzled. A runner was sent to consult with Dave. Further discussion ensued. Collective memory eventually produced a crosslike configuration with one large ring at the crossing, two smaller ones above it, and two large rings suspended by ropes in a skirt-like fashion below the crossing. On top, we placed the rooster, decked with flowers and feathers that Dave had fashioned as a decoration in imitation of poles he had seen elsewhere in the United States. Finally, the pole was ready, although without the ringed top piece needed for securing the pole with guy wires. We took a break to eat.

On his postcard invitations to Midsummer at Sealander Park, Dave always specifies times: pole decorating beginning at 1:00 p.m., pole raising and long dance at 5:00 p.m., and potluck to follow. In my experience, these times are hypothetical. When one enters the park and joins the work parties decorating the pole, one’s sense of time shifts. Rather than consulting watches, we consulted the sun and our appetites. It was probably well after 5:00 p.m, and the pole wasn’t ready, but we were ready to eat the food we had brought to share.

The potluck supper began with a blessing said by a participant who was asked, good-naturedly, because he “is a good Mormon”3 and because others denied knowing how to say grace. Everyone joined in the potluck line, where, alongside American-style cold cuts, rolls, salads, cakes, and lemonade were enough distinctively Nordic dishes to fill a plate: flavored herring, hard bread, lingonberry jam, red beet salad, rice pudding, dipped rosette cookies, boiled potatoes with skins partially peeled, scalloped potatoes with cheese. No alcohol—Dave Sealander’s mother Edith was a Latter-day Saint (LDS); her non-Mormon guests respectfully did not bring alcohol to the park. As we ate, Dave Combs continued to play, joined by another accordionist, a Danish American from Soda Springs—about three and a half hours’ drive from New Sweden. Interspersed with the Nordic folk music was a varied repertoire of popular tunes. After eating, a Finnish immigrant from nearby Firth joined in on guitar. Those so inclined joined in song, puzzling out lyrics from a songbook that the Finnish immigrant had brought.

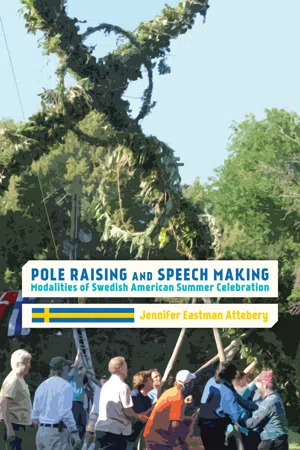

Diners and musicians lingered as dusk approached, until Dave Sealander emerged from his shop with the essential top piece, attaching it to the assembled pole. Everyone gathered in the clearing for the pole raising. The only gender- and age-specific role was at the center, where the most physically able of us used crossed poles to push the Midsummer pole higher—with a “one-two-three-ho”—and higher yet, until it was erect and ready to be lashed. Nearly everyone else helped with the three guy wires, holding them until Dave could securely fasten each one to poles at the edge of the clearing. Those few not working exclaimed at the sight: the pole suddenly taking on life as an upright focal point in the center of the park. “How lovely,” the woman next to me exclaimed, and truly, it is hard not to be moved by a Midsummer pole’s transformation as it rises to become a mast. It was 8:30 p.m., and light was beginning to fade as folk dancing around the Midsummer pole began.

Midsummer in the Spring-to-Summer Season

What could be more Swedish American than Midsummer? On June 24, or close to that date, Swedish Americans throughout the United States followed a process very similar to that at Sealander Farm. Along with St. Lucia’s Day festivals, Midsummer can be used as an index of Swedish Americanness. Writing about Midsummer in Brevort, Michigan, Lynne Swanson (1996, 24) estimates that “nearly 95 percent of the 163 Swedish American organizations affiliated with the Swedish Council of America mark the holiday in some way.” He characterizes Midsummer as “an activity strongly rooted in their [Swedish Americans’] collective identity” (Swanson 1996, 24).

The Midsummer holiday, located on the calendar either in relationship to the summer solstice or to the Catholic/Lutheran St. John’s Day (June 24), is especially important to Scandinavians and to Scandinavian emigrants to North America and elsewhere. Although often thought of as the height or middle of summer, the holiday technically marks the beginning of summer and also, ironically, the beginning of the waning of daylight. Perhaps because this phenomenon is especially apparent in northern countries such as Sweden, Norway, and Denmark, Midsummer is heightened in their calendar customs as well as in the ethnic customs of those emigrating from the Scandinavian cultural region.

In celebratory activities, people elevate ideas that they especially value, making any holiday celebration worth our attention for the sake of probing the shared values of a community. Midsummer, along with the holidays that surround and influence it in America, is well worth our attention, then, not just for its intrinsic interest as a fascinating celebratory practice but also as a window into the values of an important nineteenth/twentieth-century ethnic group, Swedish Americans. The Swedish Americans of the Rocky Mountain West are of particular interest for their continuation and reinterpretation of Swedish customs in a region where they were also very successful in adapting to Western American cultural patterns. The Rocky Mountain West’s demographic complexity, with a population including Mormon enclaves, mining towns, urban centers, and farming communities, also allows us to explore some interesting contrasts in adaptations of ethnic culture.

The Mormon enclaves are of special interest in the ways their Swedish immigrant populations both reflect some of the patterns found throughout Swedish America and counter those patterns with customs peculiar to LDS immigrants. Furthermore, because most of the ethnic Mormon population immigrated close on the heels of conversion by missionaries, we see in this part of the Rocky Mountain population a syncretic religious-ethnic identity that is neither easy nor neces...