eBook - ePub

Tradition in the Twenty-First Century

Locating the Role of the Past in the Present

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Tradition in the Twenty-First Century

Locating the Role of the Past in the Present

About this book

In Tradition in the Twenty-First Century, eight diverse contributors explore the role of tradition in contemporary folkloristics. For more than a century, folklorists have been interested in locating sources of tradition and accounting for the conceptual boundaries of tradition, but in the modern era, expanded means of communication, research, and travel, along with globalized cultural and economic interdependence, have complicated these pursuits. Tradition is thoroughly embedded in both modern life and at the center of folklore studies, and a modern understanding of tradition cannot be fully realized without a thoughtful consideration of the past's role in shaping the present.

Emphasizing how tradition adapts, survives, thrives, and either mutates or remains stable in today's modern world, the contributors pay specific attention to how traditions now resist or expedite dissemination and adoption by individuals and communities. This complex and intimate portrayal of tradition in the twenty-first century offers a comprehensive overview of the folkloristic and popular conceptualizations of tradition from the past to present and presents a thoughtful assessment and projection of how "tradition" will fare in years to come. The book will be useful to advanced undergraduate or graduate courses in folklore and will contribute significantly to the scholarly literature on tradition within the folklore discipline.

Additional Contributors: Simon Bronner, Stephen Olbrys Gencarella, Merrill Kaplan, Lynne S. McNeill, Elliott Oring, Casey R. Schmitt, and Tok Thompson

Emphasizing how tradition adapts, survives, thrives, and either mutates or remains stable in today's modern world, the contributors pay specific attention to how traditions now resist or expedite dissemination and adoption by individuals and communities. This complex and intimate portrayal of tradition in the twenty-first century offers a comprehensive overview of the folkloristic and popular conceptualizations of tradition from the past to present and presents a thoughtful assessment and projection of how "tradition" will fare in years to come. The book will be useful to advanced undergraduate or graduate courses in folklore and will contribute significantly to the scholarly literature on tradition within the folklore discipline.

Additional Contributors: Simon Bronner, Stephen Olbrys Gencarella, Merrill Kaplan, Lynne S. McNeill, Elliott Oring, Casey R. Schmitt, and Tok Thompson

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Tradition in the Twenty-First Century by Trevor J. Blank,Robert Glenn Howard in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Folklore & Mythology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Thinking through Tradition

Elliott Oring

THE WORD TRADITION IS ITSELF TRADITIONAL IN FOLKLORE studies. John Aubrey used it in his Miscellanies in 1696. In 1777 John Brand identified tradition—indeed, oral tradition—as central in the preservation of the rites and opinions of the common people (Dorson 1968a, 1:8). W. J. Thoms referred to “local traditions” in his 1846 letter to the Athenaeum where he proposed his neologism “folklore” (Dorson 1968a, 1:53), and E. Sydney Hartland, in the last years of that century, characterized folklore as the “science of tradition” (Dorson 1968a, 2:231). Tradition has remained central to most definitions of folklore ever since (Brunvand 1998, 3). Indeed, it is considered one of a few “keywords” in folklore studies (in addition to the terms art, text, group, performance, genre, context, and identity [Feintuch 2003]). But what is the status of tradition in folklore studies? What role does it play and what achievements can the field attribute to its deployment?

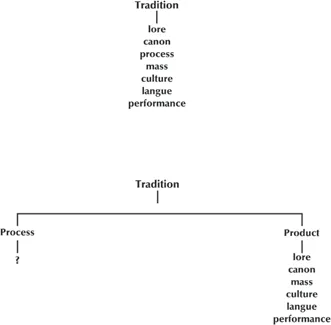

In his essay “The Seven Strands of Tradition,” Dan Ben-Amos (1984) identified a variety of ways that folklorists have used tradition: as lore, canon, process, mass, culture, langue, and performance. Lore refers to past knowledge of a society that has inadvertently survived but is in danger of dying out (104). Canon refers to that body of literary and artistic culture that has gained acceptance in a particular social group (106). Process refers to the dynamics of cultural transmission over time (117). Mass refers to what is transmitted by tradition; it is not the result of superorganic process but rather is changed by those who transmit it (118). Culture suggests that tradition is synonymous with the anthropological conception of thought and behavior in social life (120–21). Langue refers to the concepts, categories, and rules that engender culture. As in Ferdinand de Saussure’s linguistics, it refers to the abstract system that underlies and generates speech and behavior (121). Performance refers to enactment, and although enactment is always in the present, tradition always exists in the minds and memories of people as a potential (122–23).

These differences in the uses of the term tradition are not always crystal clear, but Ben-Amos was trying to sort out the usages of the term by folklorists from different periods and publications. His was an attempt to construct a descriptive history of the term. He found that folklorists did not use tradition consistently, nor did they examine their usages critically. Curiously, Ben-Amos concludes that none of the uses of the term tradition are more adequate or proper than any other. Tradition, he states, is a metaphor that guides folklorists in dealing with “an inchoate world of experiences and ideas” (Ben-Amos 1984, 124). Simon J. Bronner, writing a decade and a half later, was perhaps less forgiving. He characterizes the use of tradition in folklore as reflecting “multiple meanings” and betraying a “conceptual softness” (Bronner 1998, 10).

Can a “science of tradition” be based on a concept that is so scattered, inchoate, and soft? Ben-Amos’s seeming unconcern with the ways folklorists deployed the term tradition probably stemmed from the fact that he had no personal investment in the concept. He had eliminated tradition from his definition of folklore more than a decade before. For him, folklore was “artistic communication in small groups” (Ben-Amos 1972, 14). Tradition played no part. Ben-Amos nevertheless claimed that folklorists think with the term tradition even if they did not think much about it. Do folklorists think with tradition? Is tradition an analytical concept that helps folklorists to perceive, explore, and explain the world? These are some of the questions addressed below.

TRADITION AS PROCESS AND PRODUCT

The word tradition comes from the Latin roots trans + dare—literally, “to give across”—that is, to hand over, deliver, or transfer.1 Thus, tradition involves the notion of transferring or transmitting and has been applied to the act of handing over or handing down as well as to those objects that are handed over or handed down. Consequently, tradition refers to both processes and products.

Although folklorists have consistently noted the duality of the term, they have focused almost exclusively on the products of tradition (see Ben-Amos 1984, 116–19; Final Discussion 1983, 241; Gailey 1989, 144; Sims and Stephens 2005, 65; Vansina 1985, 3).2 They have been drawn to the field by quilts, proverbs, remedies, legends, songs, and tales. The study of folklore has always been rooted in the study of particular traditions; and the study of those traditions only sometimes turned toward the question of the means by which they were passed on.3 Folklore did not begin with a study of process and then turn to the outcomes of that process. The process was used to label objects of interest and set them apart. The process itself, however, has always remained somewhat opaque.4

Dan Ben-Amos’s survey of the uses of tradition noted that the term was employed to denote both process and product, but that distinction was obscured as he listed all seven uses indiscriminately. Process is listed with six other uses that refer to products of tradition—namely, lore, canon, mass, culture, langue, and performance (Ben-Amos 1984, 102–25). These products are the ideas, knowledge, objects, behaviors, or rules that are transferred and transmitted through time. Had Ben-Amos arranged the categories taxonomically, however, with the first distinction drawn between process and product, the fact that the other six categories were—or dealt with—product would have stood out more clearly. Then the deficiency of attention to tradition as process would have been underscored, as process would have included no further categories.

The collapse of process and product into a simple list obscures the fact that process is not just another entry. It does not constitute a mere one-seventh of the meanings of tradition. It represents a fundamentally different conceptualization of what constitutes tradition. Process is more fundamental than product. Traditions are traditions only by virtue of some process that makes them so. Process creates product. Without the process, traditions would be indistinguishable from all other cultural ideas and practices.

What, then, is this process? The process of tradition, I contend, is the process of cultural reproduction. Cultural reproduction refers to the means by which culture is reproduced in transmission and repetition.5 It depends on the assimilation of cultural ideas and the reenactment of cultural practices. Reproduction may be accomplished in an act of transmission from one person to another. Or it may be accomplished when individuals produce something they have reproduced before, such as singing a song they have sung in the past (Bartlett 1932, 63, 118). My use of cultural reproduction refers to a much broader sphere of activity than that addressed by Pierre Bourdieu in his study of French educational institutions. The term should not be restricted to school learning or the learning of “high” or “official” culture. A study of cultural reproduction need not focus on the ways that it preserves social stratifications (Bourdieu 1973; Bourdieu and Passeron 1977). Indeed, folklorists should be more interested in how social organizations enable cultural reproduction than the reverse. In reality, cultural reproduction is achieved through a number of different processes. Cultural reproduction is merely an umbrella term for these processes—the processes of tradition.

It is even possible to identify some of these processes within Ben-Amos’s essay. When he discusses the sense of tradition as canon, for example, he talks about creativity and how folklorists view creativity as necessary to the maintenance of tradition. Creativity—or better, re-creation—would then be one of the processes of tradition. Canons are products, but canonization is a process, so it might be included as well. Beyond Ben-Amos’s essay, other processes spring immediately to mind: education, memorization, rehearsal, comparison, and traditionalization.6

TRADITION AND CREATIVITY

Everything changes. What comes from the past mutates and is modified, transformed, or disappears. There are two possible approaches to the past and change: take the past as given and describe and explain change; or take change as given and describe and explain that which perseveres. The attention of contemporary folklorists is unequally distributed with respect to these approaches. For the most part, folklorists take the past as given and address themselves to variation (Ben-Amos 1984, 114). Each instantiation of a tradition is regarded as a performance with its own peculiar variables. Rather than being something handed down, it is highlighted as something new and unique.7 It has even been claimed that “tradition is change” (Final Discussion 1983, 236; Toelken 1996, 7).

Of late, the attention of folklorists has been directed to one type of change: change that is deliberate, crafted, and aesthetic. The terms for this type of change are innovation, improvisation, and creativity.8 Folklorists hold that it is creativity that keeps tradition alive by making an inheritance from the past relevant in the present (Ben-Amos 1984, 113; Glassie 1995, 395). 9 However, there are several problems with this proposition.

There is a presumption that the changes that occur to past ideas, expressions, and behaviors are necessary ones. For example, “Folklore lives through a generally selective process that ensures … that traditions will maintain their viability, or change so they can, or die off” (Toelken 1996, 43). “Only those forms are retained that hold a functional value for the given community” (Jakobson and Bogatyrev 1980 [1929], 6). “Creative storytellers are the ones who modernize and renew the folktale tradition to make it attractive for current consumption” (Dégh 1995, 44). “The creative impulse speaks to the fact that tradition is not and has never been something static, the most stable aspect of any tradition being its ability to change in response to changing needs” (Neulander 1998, 226). These claims, however, are merely assertions. Change and adaptation have not been assessed independently but are defined in terms of one another. The change of past forms is required for survival in the present; survival in the present demands change in forms from the past.10 However, without some empirical determination of what constitutes necessary and incidental change, what has been proposed is tautology: the changes that have occurred to an expression from the past enable its survival; expressions from the past that have not survived did not change appropriately to suit current conditions. In other words, that which survives, survives; that which has not, has not.11

Creativity is a term for a process that is applied to a product. Because creativity is a process, it is conflated with the process of tradition itself. But the process of tradition, whatever its particular characteristics, must conceptually relate to a process of cultural reproduction, not innovation. Things from the past can be altered. Things from the past are altered. Things from the past are “creatively” or otherwise revised. But to call this the process of tradition is to largely ignore continuity and stability. Continuity and stability depend on what people preserve—for good or ill, consciously or unconsciously—of the thought and behavior of the past. To study tradition, folkloristics must come to understand the means by which cultural reproduction is accomplished—to grasp the forces that direct the present through the conduit of past practice.

The notion of creativity as employed by folklorists is not the process of tradition but a process acting upon particular traditions (Bronson 1969, 144–45). For example, would the creative refashioning of a ballad or folktale constitute the operation of tradition or an operation performed on a traditional expression? The use of a single term to at once refer to both a process and a product is probably the source of many problems with the term tradition. Some statements that might be true about tradition as product (e.g., “traditions change”) are ambiguous, meaningless, or false when applied to tradition as process (e.g., “tradition is change” [Final Discussion 1983, 236; Toelken 1996, 7]). Some statements that might be true about tradition as process (e.g., “tradition never dies”) are ambiguous, meaningless, or false when applied to a product (e.g., “traditions never die”).

Contemporary folklorists have been trapped by tradition. Like Ben-Amos (1972), they have moved away from the concept. Unlike Ben-Amos, they did not consciously or precipitously abandon it. Almost alchemically, they transformed it. The continuity of the past was regarded as a given. The focus was on change, particularly creative change, which became the touchstone of tradition: “Tradition … is an innovativ...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Living Traditions in a Modern World

- 1 Thinking through Tradition

- 2 Critical Folklore Studies and the Revaluation of Tradition

- 3 Vernacular Authority: Critically Engaging “Tradition”

- 4 Asserting Tradition: Rhetoric of Tradition and the Defense of Chief Illiniwek

- 5 Curation and Tradition on Web 2.0

- 6 Trajectories of Tradition: Following Tradition into a New Epoch of Human Culture

- 7 And the Greatest of These Is Tradition: The Folklorist’s Toolbox in the Twenty-First Century

- 8 The “Handiness” of Tradition

- About the Contributors

- Index