eBook - ePub

River Flowing From The Sunrise

An Environmental History of the Lower San Juan

James M Aton

This is a test

Share book

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

River Flowing From The Sunrise

An Environmental History of the Lower San Juan

James M Aton

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The authors recount twelve millennia of history along the lower San Juan River, much of it the story of mostly unsuccessful human attempts to make a living from the river's arid and fickle environment. From the Anasazi to government dam builders, from Navajo to Mormon herders and farmers, from scientific explorers to busted miners, the San Juan has attracted more attention and fueled more hopes than such a remote, unpromising, and muddy stream would seem to merit.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is River Flowing From The Sunrise an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access River Flowing From The Sunrise by James M Aton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Environmental Conservation & Protection. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 PREHISTORY: From Clovis Hunters to Corn Farmers

Humans have hunted and herded animals, gathered and cultivated plants, and generally made a living in the San Juan River area for at least the last twelve thousand years. Although always a marginal area, the river valley’s population reached a high point during the Anasazi occupation between 1500 B.C. and A.D. 1300.1 During this prehistoric period, the San Juan landscape was certainly no untouched Eden. To be sure, since Euro-Americans entered the San Juan country and applied the technology of the Industrial Revolution, they have changed the landscape more dramatically than both prehistoric and historic Indians. Yet, before one accounts for that massive environmental change, it is crucial to understand the roughly twelve thousand years preceding it.

Although pre-Columbian Indians in the San Juan basin manipulated their environment, the influence of climatic variation cannot be ignored. During the prehistoric period, the San Juan changed from an Ice-Age climate with cooler temperatures and much more precipitation to the drier, warmer weather it now experiences. The first recognized and established entrants into the San Juan, the Clovis hunters, and their successors, the Folsom hunters, lived during the five-hundred-to-thousand-year transition from the cool, wet Pleistocene to the warm, drier Holocene. Moreover, all the prehistoric groups that archaeologists distinguish—Clovis, Folsom, Plano, Archaic, and Anasazi—had to cope with climatic changes during their tenure on the San Juan. They all made land-use decisions based on the environmental deck nature dealt them, on the skills and tools they had to play the game, and on the imaginative and cultural ideas they brought to the table. Often they hedged their bets wisely, but other times they overplayed their hands. None of these groups lived in perfect harmony with the San Juan landscape, although the Archaic lifeway persisted longer than any other.

Interest in San Juan prehistory has focused largely on the Anasazi from roughly 1500 B.C. to A.D. 1300. The Anasazi fired the imagination of the American public in large part because, in contrast to Indian groups before and after, they built magnificent structures. More than other Native American groups in the area, they reflected a Euro-American definition of civilization. The often-neglected groups of prehistoric Indians in the San Juan area, however, deserve equal consideration. It is crucial to understand how the hunting-gathering Clovis, Folsom, and Archaic Indians manipulated the San Juan environment and changed themselves in the process.

In the late Pleistocene, sometime around 10,000 to 9000 B.C., the Clovis hunters walked into the San Juan area. This is what they found: Weather conditions were cooler and wetter, but today’s temperature extremes did not exist. Rather than four seasons, two split the climatic year: a mild, cool summer and a wet, cold winter. The growing season extended longer, and plant species varied considerably, unlike the relatively less diverse environment of the Holocene, 8000 B.C. to the present.2

A twentieth-century visitor to the late-Pleistocene San Juan River would be shocked to see what luxuriant vegetation grew in the bottoms as well as how massive the river flows were. That time traveler would find plants flourishing now commonly found on Navajo Mountain, Elk Ridge, or in the Abajo Mountains. A few would be barely recognizable. Tall Douglas firs, white birch, limber pines, and blue spruce lined the banks of the river and its tributaries. Also common were red osier dogwood, alderleaf mountain mahogany, wild rose, and Rocky Mountain and common juniper. The more recognizable plants would have been Mormon tea, prickly pear cactus, narrowleaf yucca, cattails, big sage, and Indian ricegrass.3 This green, rich environment was just the kind of place that attracted Columbian mammoths, Shasta ground sloths, Yesterday’s camel, and other giant animals of the late Pleistocene. For the Clovis hunters, it probably was “a veritable Garden of Eden.”4

Indian ricegrass has been a staple of southwestern Indian diets since the first Clovis hunters. It was ground into a meal and also made into a drink. (James M. Aton photo)

Although it is unclear exactly who were the first Americans and when they arrived, the Clovis hunters (named after Clovis, New Mexico, where their artifacts were first discovered and identified) remain the first verifiable group of humans in the New World. While a few possible pre-Clovis sites have been excavated by archaeologists at places like Monte Verde in Chile and Meadowcroft Rock Shelter near Pittsburgh, none of them has passed all the criteria established by archaeologists.5 This situation is changing rapidly, and many archaeologists privately think a pre-Clovis presence will soon be accepted. Clovis points, however, have turned up in every state in the U.S. The majority of these sites lie on the Great Plains, but at least a score of them are on the Colorado Plateau.6 One sits on Lime Ridge, overlooking Comb Wash and the San Juan River.7

What brought these hunters to the San Juan area apparently was the presence of Columbian mammoths and an occasional mastodon. Clovis hunters probably traveled in groups of forty or fewer, including both sexes and all ages. Although they appear to have specialized in these two large animals, they also hunted other large herbivores, such as camels, ground sloths, long-horned bison, giant short-faced bears, horses, and musk oxen. When time and opportunity presented themselves, they also probably caught rabbits, wild turkey, and other smaller animals. Wild vegetables no doubt formed part of their diet during the warm season.8 Like any hunters, the Clovis people were opportunists, but they probably preferred mammoths. Within five hundred years or less, however, mammoths were extinct. Clovis hunters may have been the culprits.

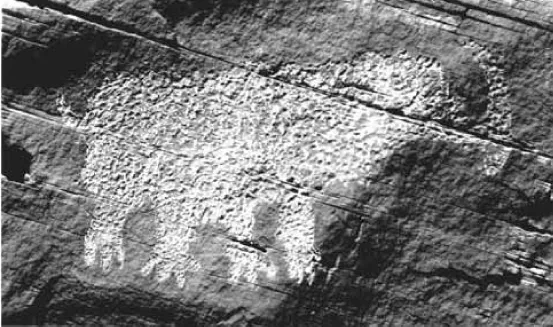

The Moab mastodon—real or fake? This petroglyph was found near Moab, Utah and then “enhanced” by its finder. Archaeologists debate its authenticity, but mastodons and mammoths did roam the Colorado Plateau until about eleven thousand years ago. (San Juan Historical Commission)

The extinction question has drawn much attention precisely because one interpretation of it is an archetypal story of the Fall. Subsequent Native American groups might come and go, like the Navajos whose sheep overgrazed the hills north of Bluff, but somehow those environmental trespasses seem less portentous. This creation story says that when people entered the Garden, they destroyed a vital, even totemic, part of that paradise: those magnificent mammoths which waded along the lush bottoms of Comb and Butler Washes. These people—the Clovis hunters—might have committed the Original Sin of the Americas.

We explore this extinction possibility in depth because it reveals crucial information about the changing San Juan environment. It shows what kinds of plants and animals inhabited the area. It demonstrates the way climatic change affected aspects of the landscape. And it throws in the human element: the application of technology to manipulate an environment, along with the cultural and ethical values that accompanied it. Whatever the exact source of the Pleistocene extinctions, this creation narrative frames an important question for the rest of this book. The complete story of the San Juan River demands that we ask not only what the river landscape looked like, but what people found and did there. One can view the mammoth-extinction story as the beginning script of a San Juan River palimpsest.

Standing twelve to fourteen feet tall and weighing upward of twenty thousand pounds, Columbian mammoths appeared in North America nearly two million years before the Clovis people. They grazed on grasses and shrubs, their flat teeth especially suited for grinding.9 These giant creatures ate prickly pear, gambel oak, grass flowers, sedge, birch leaves, rose, saltbush, big sage, and smaller amounts of blue spruce, waffleberry, and dogwood.10 All of these plants flourished in the moist bottoms of the San Juan and its tributaries like Comb Wash.

By the time the Clovis hunters arrived, possibly because the environment was drying out, mammoths appear to have been congregating near water sources. This seems especially true on the now-arid Colorado Plateau.11 It may account for the Lime Ridge campsite near the San Juan; it was probably a hunting stand from which Clovis Indians stalked mammoths in either Comb Wash near camp or along the San Juan River, a short distance to the south. The Lime Ridge site was perfectly situated to give Clovis hunters a long view of these drainages, all the while staying upwind. It offers a 360-degree view of the surrounding area, and in particular overlooks a side canyon that runs into Comb Wash. This drainage was probably a corridor for animals to move between the Lime Ridge uplands and the lower riparian zone.12

From this Lime Ridge campsite, Clovis hunters had direct access to Comb Wash and the San Juan River via the drainage below. Archaeologists believe this high point gave the Clovis hunters a view of mammoths along the river drainages. (James M. Aton photo)

The hunters probably ambushed several mammoths from sites like Lime Ridge. Female mammoths and their offspring would have been especially vulnerable to mass killings because elephants behave altruistically. Studies of elephant behavior in Africa reveal that if one is killed, others (especially females around offspring) will rally around, making them easier prey.13 Other scholars believe that while Clovis hunters did not habitually kill groups of mammoths, they would have if the opportunity presented itself.14 But kill mammoths they definitely did. The question is to what extent?

At the end of the Pleistocene, both flora and fauna underwent major changes in the Americas. As the climate warmed and dried along the San Juan, for example, plant communities started to crawl up the drainages and slopes toward the ridges and mountains, chasing a cool, wet climate. The blue spruce-limber pine-Douglas fir communities once lining the San Juan ended up on Navajo Mountain, Elk Ridge, and the Abajos. Pinyon-juniper woodland communities from the lower Sonoran and Mojave Deserts, in turn, replaced them. Desert shrub communities, likewise, took over from pinyon-juniper.15 Plant environments were changing radically, and species of megafauna in the San Juan and elsewhere, like the much-hunted Columbian mammoth, became extinct. Was it because of climate change or due to the Clovis hunters?

For years scientists had assumed that the giant mammals of the Pleistocene died gradually because the weather patterns altered and the ensuing Holocene environment no longer supported them. Many still hold climate to be the culprit. But in 1967, Arizona archaeologist Paul S. Martin first proposed the “overkill thesis”: Clovis people had hunted the megafauna to extinction. In his groundbreaking work, Martin showed that some thirty-one genera of large mammals disappeared about ten thousand years ago. He theorized that these animals had evolved without fear of human hunters. When the first hunters arrived in America, “there was insufficient time for the fauna to learn defensive behaviors.”16 The result was a hunting blitzkrieg.

In a mere one thousand years, he postulated, a band of forty Clovis hunters could have spread throughout the Americas and multiplied to over a half-million people, wiping out the vulnerable mammoths and other megafauna as they went. Unaware of what they were doing, the Clovis hunters kept pushing on to new hunting grounds, taking the easy prey; perhaps at times they even wasted much of the mammoth because there were so many. When the large animals disappeared, Martin said, populations crashed, and hunters turned to other animals and food-gathering strategies.17 Following this massacre, mammoths, mastodons, and other giants no longer lumbered along the lush bottomlands of the San Juan, eating sedge and ricegrass. After two million years in North America, all that remains of the mammoths are piles of bones and desiccated turds. If Paul Martin is correct, these first Americans were responsible for perhaps the most dramatic of many extinctions in North America.

Not all archaeologists and paleontologists, however, accept Martin’s thesis, and there is fierce debate. Many believe that the appearance of Clovis hunters and mass extinctions were a coincidence. Climate alone might have delivered the knockout punch. These Ice-Age mammals had coevolved with certain kinds of plant communities, which began to change between 10,000 and 9000 B.C. For many of these megaherbivores (large plant eaters) like the mammoth, a reduction in the kinds of plants they preferred created greater competition with other animals.18 Moreover, the change from a two-season to a four-season year meant that many plants that mammoths browsed on no longer had a full growing season. Thus, plant diversity declined, and megaherbivores might have found it increasingly difficult to forage for the high-protein diet they needed. They would have been pushed to eat lower-protein plants with higher toxins. As a result, megafauna with conservative digestive systems would have lost out to animals which could adapt....