eBook - ePub

Applied Pedagogies

Strategies for Online Writing Instruction

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Applied Pedagogies

Strategies for Online Writing Instruction

About this book

Teaching any subject in a digital venue must be more than simply an upload of the face-to-face classroom and requires more flexibility than the typical learning management system affords. Applied Pedagogies examines the pedagogical practices employed by successful writing instructors in digital classrooms at a variety of institutions and provides research-grounded approaches to online writing instruction.

This is a practical text, providing ways to employ the best instructional strategies possible for today's diverse and dynamic digital writing courses. Organized into three sections—Course Conceptualization and Support, Fostering Student Engagement, and MOOCs—chapters explore principles of rhetorically savvy writing crossed with examples of effective digital teaching contexts and genres of digital text. Contributors consider not only pedagogy but also the demographics of online students and the special constraints of the online environments for common writing assignments.

The scope of online learning and its place within higher education is continually evolving. Applied Pedagogies offers tools for the online writing classrooms of today and anticipates the needs of students in digital contexts yet to come. This book is a valuable resource for established and emerging writing instructors as they continue to transition to the digital learning environment.

Contributors: Kristine L. Blair, Jessie C. Borgman, Mary-Lynn Chambers, Katherine Ericsson, Chris Friend, Tamara Girardi, Heidi Skurat Harris, Kimberley M. Holloway, Angela Laflen, Leni Marshall, Sean Michael Morris, Danielle Nielsen, Dani Nier-Weber, Daniel Ruefman, Abigail G. Scheg, Jesse Stommel

This is a practical text, providing ways to employ the best instructional strategies possible for today's diverse and dynamic digital writing courses. Organized into three sections—Course Conceptualization and Support, Fostering Student Engagement, and MOOCs—chapters explore principles of rhetorically savvy writing crossed with examples of effective digital teaching contexts and genres of digital text. Contributors consider not only pedagogy but also the demographics of online students and the special constraints of the online environments for common writing assignments.

The scope of online learning and its place within higher education is continually evolving. Applied Pedagogies offers tools for the online writing classrooms of today and anticipates the needs of students in digital contexts yet to come. This book is a valuable resource for established and emerging writing instructors as they continue to transition to the digital learning environment.

Contributors: Kristine L. Blair, Jessie C. Borgman, Mary-Lynn Chambers, Katherine Ericsson, Chris Friend, Tamara Girardi, Heidi Skurat Harris, Kimberley M. Holloway, Angela Laflen, Leni Marshall, Sean Michael Morris, Danielle Nielsen, Dani Nier-Weber, Daniel Ruefman, Abigail G. Scheg, Jesse Stommel

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Applied Pedagogies by Daniel Ruefman, Abigail G. Scheg, Daniel Ruefman,Abigail G. Scheg in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Creative Writing. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

Course Conceptualization and Support

1

Return To Your Source

Aesthetic Experience in Online Writing Instruction

DANIEL RUEFMAN

The controversy surrounding the online writing classroom is something that I have been well aware of, ever since I began studying them as a graduate student. One of my mentors at that time informed me of just how online writing instruction was creating a culture of academic mediocrity. At the time, he had never seen a study that indicated definitively that online instruction was more effective than face-to-face, though some studies at the time indicated that students were achieving outcomes in the online classroom at a comparable rate with those in more conventional classrooms.

During the 2009–2010 academic year, I found myself engaged with a series of case studies that would ultimately form my dissertation. The goal was to gain a better understanding of the pedagogical practices implemented by first-year writing instructors in face-to-face, online, and hybrid courses. Over the course of this investigation, I quickly realized the online course I was observing was using far less technology than the instructors who taught in the other two settings (Ruefman 2010). While instructors in the face-to-face and hybrid classrooms freely used a variety of web-based technologies, like YouTube and Second Life, the instructor in the online course provided directions for course activities in the form of cumbersome paragraphs supplemented with PDFs and Word Documents (figure 1.1). Essentially, the instructor whose class existed only because of web-based multimodal technologies created a monomodal, text-heavy course that used these technologies less than the other instructors sampled for these case studies.

Following the defense of my dissertation, I constantly revisited the original case study and began to wonder if these findings were limited to this single instructor or whether they were indicative of a larger trend in online writing instruction. As I continued this line of inquiry, much of what I found mirrored those original findings. Most of the sampled instructors facilitated text-heavy, monomodal courses that embodied a highly transactional pedagogical model. Modules often contained large passages of text and typed course materials that were uploaded on the course management systems (CMS).

These one-dimensional courses are simply not compatible with the way the human brain is wired to learn. Over the millennia, the human brain has been wired to respond to external sensory stimuli; sight, sound, taste, touch, and smell were the primary way that we learned about the world. Scientific discovery is propelled by experimentation and the observations made are often based upon what the scientists see, hear, taste, feel, or smell. When educational environments are devoid of sensory stimuli, they become sterile and inaccessible to many students.

KOLB’S EXPERIENTIAL LEARNING THEORY AND AESTHETIC EXPERIENCE

Before it is possible to comprehend the importance of aesthetic experience in online education, an understanding of the terminology is required. Aesthetics, in contemporary terms, often refers to concepts of pleasure or artistic beauty. Further exploration reveals that the term is actually derived from aesthetikos, a Greek word that translates as “capable of sensory perception” (Uhrmacher 2009). An aesthetic learning experience is therefore not one that is deemed as “pleasurable” or “beautiful,” but it is one that is made tangible by the senses—sight, sound, taste, touch, or smell.

Sir Ken Robinson is an educational scholar who has previously touched on the need for aesthetics in American public education. In his presentation entitled “Changing the Paradigm,” he explains that “aesthetic experience is one in which your senses are operating at their peak, when you are present in the current moment, when you are resonating with this thing that you are experiencing, when you are fully alive. An anesthetic is when you shut your senses off and deaden yourself to what is happening” (Robinson 2010). By creating one-dimensional, text-heavy online courses, writing instructors are fostering anesthetic, sterile experiences that require students to shut their senses off, depriving them of the learning tools gifted to them by the nature of human biology.

To further understand the role that aesthetic experience plays in learning, it is vital to refer to David A. Kolb’s experiential learning theory. Kolb explains that experiential learning is rooted in the concept that “ideas are not fixed and immutable elements of thought but are formed and re-formed through experience . . . knowledge is continuously derived from and tested out in the experiences of the learner” (Kolb 1984). For him, knowledge stems from a process of active experimentation, whereby the learner continually tests what they know and amends their understanding based on the results.

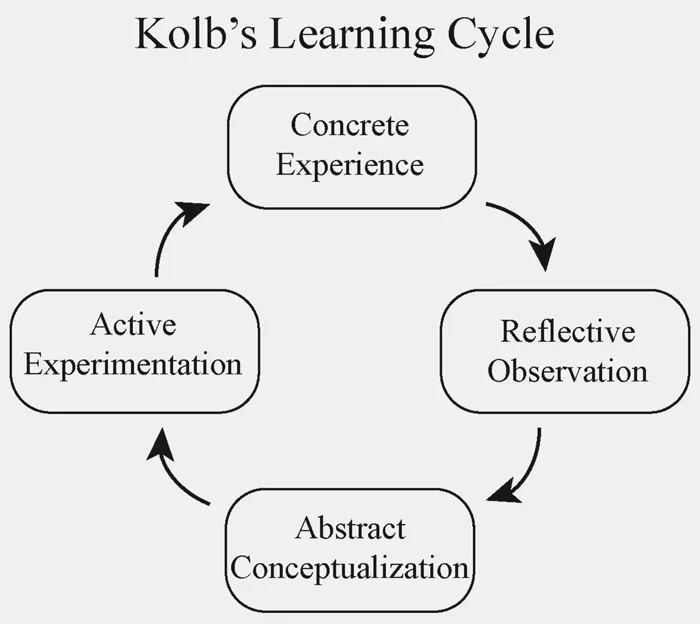

Learning can be best understood as a cycle. It consists of four different stages: (1) concrete experience, (2) reflective observation, (3) abstract conceptualization, and (4) active experimentation. For Kolb, learning is best thought of as a cycle, that has no definitive beginning or end. Depending on the learning style of the student, their preconceptions, beliefs, or experiences will often cause them to resume their learning process at a different stage of the cycle, but ultimately all four stages must be encountered to truly build knowledge.

Figure 1.1. Depiction of a simplified version of Kolb’s learning process as described in his seminal work, Experiential Learning (Kolb 1984)

To better illustrate the learning process, consider the way you learn a new word. You first encounter that term through one of your senses. Perhaps someone uses it in conversation and you hear it. Maybe you see the written term while reading a book or article. The sensory input serves as a tangible, concrete experience that jumpstarts the learning process. Following that initial experience, a period of reflective observation will usually follow, where your experience is committed to memory. In this process, you begin to store the experience for future recall, remembering how the word looked or how it sounded in that initial context. Once committed to memory, you will transition to a stage of abstract conceptualization where you use the context clues to attribute meaning to the new term you are trying to understand. At this time, you recall things that you have already learned, meaning prefixes, suffixes, root words, and the other words that were mentioned or written around the new term. This is where critical thinking skills enable you to begin theorizing what the new term might mean and you begin to strategize ways that you might use this word in the future. Finally, the cycle proceeds to active experimentation where you put your plan into motion by using the new term in conversation or in your own writing. Often, this use of the new term will lead to another concrete experience. Perhaps feedback from your audience informs you that the term was misspelled or pronounced incorrectly, and that information is processed, building upon the previous lessons to establish a more refined concept of the new word.

Although there are different learning styles that impact how individuals move through these four stages, most true learning seems to conform to the process summarized by Kolb. The reason why is actually found in the more recent work of biologist, James E. Zull. Zull’s book, The Art of Changing the Brain, maps many of the mind’s structures, illustrating why Kolb’s learning process seems to work so well. Zull (2002) argues that humans are simply biologically wired to learn in this way. According to Zull, if we examine the structures and functions of the human brain, we can observe that Kolb’s learning process mirrors the organization of the brain’s structures.

There are four regions of the cerebral cortex that Zull draws our attention to—the sensory cortex, temporal integrative cortex, frontal integrative cortex, and motor cortex. He goes on to state that “the sensory cortex receives first input from the outside world in form of vision, hearing, touch, position, smells, and taste. This matches with the common definition of concrete experience” (Zull 2002). In short, Zull is tracing the most basic components of Kolb’s learning cycle, beginning with a sensory rich, concrete experience. When sensory stimuli are received by the brain, these impulses are concentrated in the sensory cortex, located toward the rear of the br...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- Part One: Course Conceptualization and Support

- Part Two: Fostering Student Engagement

- Part Three: MOOCs

- About the Authors

- Index