- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Maya Narrative Arts

About this book

In Maya Narrative Arts, authors Karen Bassie-Sweet and Nicholas A. Hopkins present a comprehensive and innovative analysis of the principles of Classic Maya narrative arts and apply those principles to some of the major monuments of the site of Palenque. They demonstrate a recent methodological shift in the examination of art and inscriptions away from minute technical issues and toward the poetics and narratives of texts and the relationship between texts and images.

Bassie-Sweet and Hopkins show that both visual and verbal media present carefully planned narratives, and that the two are intimately related in the composition of Classic Maya monuments. Text and image interaction is discussed through examples of stelae, wall panels, lintels, benches, and miscellaneous artifacts including ceramic vessels and codices. Bassie-Sweet and Hopkins consider the principles of contrast and complementarity that underlie narrative structures and place this study in the context of earlier work, proposing a new paradigm for Maya epigraphy. They also address the narrative organization of texts and images as manifested in selected hieroglyphic inscriptions and the accompanying illustrations, stressing the interplay between the two.

Arguing for a more holistic approach to Classic Maya art and literature, Maya Narrative Arts reveals how close observation and reading can be equally if not more productive than theoretical discussions, which too often stray from the very data that they attempt to elucidate. The book will be significant for Mesoamerican art historians, epigraphers, linguists, and archaeologists.

Bassie-Sweet and Hopkins show that both visual and verbal media present carefully planned narratives, and that the two are intimately related in the composition of Classic Maya monuments. Text and image interaction is discussed through examples of stelae, wall panels, lintels, benches, and miscellaneous artifacts including ceramic vessels and codices. Bassie-Sweet and Hopkins consider the principles of contrast and complementarity that underlie narrative structures and place this study in the context of earlier work, proposing a new paradigm for Maya epigraphy. They also address the narrative organization of texts and images as manifested in selected hieroglyphic inscriptions and the accompanying illustrations, stressing the interplay between the two.

Arguing for a more holistic approach to Classic Maya art and literature, Maya Narrative Arts reveals how close observation and reading can be equally if not more productive than theoretical discussions, which too often stray from the very data that they attempt to elucidate. The book will be significant for Mesoamerican art historians, epigraphers, linguists, and archaeologists.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Publisher

University Press of ColoradoYear

2019Print ISBN

9781607327417, 9781607328216eBook ISBN

97816073274241

The Creator Grandparents and the Place of Duality

There are abundant depictions of deities in Maya art and references to them in hieroglyphic texts. It is our contention that a family of creator deities is at the heart of this diverse pantheon, and that kinship and complementary opposition are the key organizing principles among these deities (Bassie-Sweet 2008). The most comprehensive source regarding the family of creator deities family is contained in the Popol Vuh, an extraordinary piece of literature that was written by members of the Postclassic K’iche’ aristocracy after the Spanish conquest (Christenson 2003a, 2003b). The Popol Vuh contains an ancient core myth about the creation of the world and humans by a group of primordial deities. The meager artwork left behind by the K’iche’ does not even hint at this rich mythology; however, episodes from the Popol Vuh story have long been used to explain some of the mythology illustrated in lowland Classic-period art. The Popol Vuh relates the deeds of three generations of deities: the creator grandparents called Xpiyacoc and Xmucane; their sons, One Hunahpu and Seven Hunahpu; and One Hunahpu’s sons, named One Chouen, One Batz, Hunahpu, and Xbalanque (Christenson 2003a). Classic-period lowland parallels for all of these gods have been identified (Coe 1973, 1977, 1989; Taube 1985, 1992a; Bassie-Sweet 1996, 2008; Zender 2004a) (figure 0.2).

The Maya often categorize, organize, and structure their world using complementary opposition such as male/female, right/left, and senior/junior (see Bassie-Sweet 2008:3–4 for an overview). This concept was a fundamental principle in the ancient Maya worldview, and it was reflected in all aspects of life. In this and the following chapter we review the manifestations and complementary nature of the major Popol Vuh deities and their Classic-period parallels, and explore how this family of primary deities functioned as role models for humans. The physical environments in which these deities operated is also discussed. This will provide a framework for understanding the events and ceremonies illustrated in Maya art. We begin with an overview of terms related to deities.

The Nomenclature and Manifestations of Maya Deities

Paul Schellhas (1904) categorized the various deities in the three Postclassic codices from northern Yucatán and gave them alphabetic designations. Many of these Postclassic deities or close variations of them also occur in Classic-period art. In some cases, the name glyph of a deity has not been deciphered so the Schellhas designation is retained.

In Maya epigraphy, the head of God C (T1016) with its prefix (T35–40) is taken to represent the word k’uh, meaning “god” (Barrera Vásquez 1980:416). A common occurrence of this compound is in Emblem Glyphs, where the head is positioned behind the place glyph, leaving only the prefix visible. There are no phonetic complements or substitutions to insure the reading, which might in some cases take its Cholan form ch’u(h) as well (Montgomery 2002:243–245). In either case, the term is derived from proto-Mayan *k’uuh (Kaufman 2003:458–460) and is well distributed throughout the Mayan family.

The meanings associated with the reflexes of *k’uuh vary somewhat. About equal numbers of languages in Kaufman’s cognate list report the primary meaning of the term to be “god,” “sun,” “day,” and “thunder/lightning” (trueno, rayo). However, the meaning “god” prevails in Yucatecan and Cholan languages—the languages most closely associated with Classic culture—and the latter meaning occurs only in the Cuchumatanes, where “sun” and “day” are alternate meanings. The proto-Mayan term *q’iinh (Kaufman 2003:461–463), giving Epigraphic Maya k’in, has the meaning “day, sun” in almost all Mayan languages, but the languages of the Cuchumatanes have shifted the meaning to “fiesta” (and k’uh means “day,” as in Chuj hoye k’uh, Five Days, the period corresponding to the ancient Wayeb).

In Ch’ol (Hopkins et al. 2011:50), the root ch’uj “holy” is an adjective, as in ch’uj-tye’ “cedar” or “holy wood” (from which sacred figures are carved), and ch’uj-lel “soul.” It commonly occurs with the addition of a suffix, ch’uj-ul, as in ch’ujul tyaty “holy father” or “God.” The suffixed form may reduce to ch’ul, or this may be an independent development: in Bachajón Tzeltal (Slocum and Gerdel 1980:136–137) the three forms chuh ~ ch’uj ~ ch’ul occur with the same meanings. In early modern Ch’ol sources (Starr 1902:96; Becerra 1935:273) the form ch’ul was attested as “holy,” as in ch’ul tyaty “saint, Sun” (literally, “holy father”).

In Maya of Yucatán (Barrera Vásquez 1980:416–423), the meanings “day” and “sun” are assigned to k’in, and k’u and its derivatives are associated with divinity: k’u “God,” k’u na “temple,” k’uil “divinity,” as well as k’ul “adoration, to adore, sacred thing.” Kaufman (2003:459) takes the latter to derive from the suffixed form *k’uh-ul, attested in Epigraphic Maya and common throughout the Greater Lowlands (Yucatecan, Cholan, Tzeltalan, and neighboring languages), with the meaning “divine (thing).”

The Multiple Manifestations of Deities and Humans

Some of the major Maya deities such as the creator grandfather Itzamnaaj, his wife Ix Chel, and the Chahk thunderbolt deities have quadripartite forms that are related to the four quadrants of the world and their associated colors (east-red, north-white, west-black, and yellow-south). In addition, Maya deities have multiple manifestations that relate to their various functions and duties. These manifestations could have the form of flora, fauna, geological formations, or natural phenomena like lightning, whirlwinds, and meteors. As an example, the deities designated as God D and God N were different manifestations of Itzamnaaj.1 Generally speaking, God N is identified with earthly locations and his diagnostic trait is a net bag headdress while the celestial God D is a conflation of God N and his avian manifestation. Itzamnaaj also had turtle, conch, opossum, and peccary manifestations. The first two forms are obviously associated with water and the latter are identified with fire in Mesoamerican thought. As will be discussed later, Itzamnaaj was the source of the fire and heat that engendered life.

The Maya believe that humans have co-essences that can take the form of fantastic animals or phenomena like thunderbolts, whirlwinds, and meteors. Houston and Stuart (1989) and Grube and Nahm (1994) independently deciphered a glyph (way) that represents this concept. Given that the deities were role models for human behavior, the notion that humans have supernatural manifestations is clearly linked to the concept that deities had many forms of manifestation.

The Chahk Deities

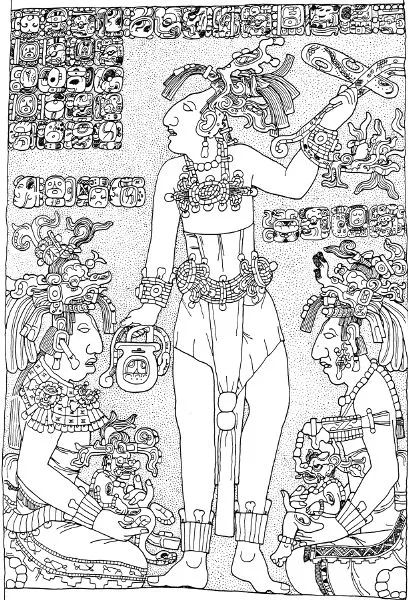

In the Popol Vuh, the family of creator deities interacts with a triad of thunderbolt gods who reside in the sky called Thunderbolt Huracan, Youngest Thunderbolt, and Sudden Thunderbolt. The Chahks (God B in the Schellhas system) are thunderbolt gods. They are often portrayed as zoomorphic creatures wearing a Spondylus-shell earring, and such portraits are used to represent the word chahk “thunderbolt.” Pars pro toto representations are common in Maya art, and the Chahk’s shell earring is used as an abbreviated reference for the word chahk “thunderbolt” in hieroglyphic writing. There is a common Maya belief that lightning bolts are the axes of the thunderbolt gods, and that they can also take the form of snakes (both strike with fast, deadly results). A clear example is found on the Dumbarton Oaks Tablet originally from the Palenque region (figure 1.1). In this scene, the young K’inich K’an Joy Chitam II is shown dancing in the costume of a Chahk deity while swinging a lightning axe. The handle of the axe has the form of a serpent. There are many different kinds of Chahk deities with names that include references to age, color, rain, clouds, fire, and the sky (Grube 2000; Lacadena 2004; García Barros 2008).

The Triad of Thunderbolt Gods

Berlin (1963) identified three gods in the Classic-period texts of Palenque, and he gave them the nicknames GI, GII, and GIII because their nominal glyphs were not deciphered at the time. When these gods are named together as a triad the order is always given as GI, GII, and GIII, but according to the Palenque Cross Group narrative, the birth order of these three brothers was GI, GIII, and GII. All three of these gods have thunderbolt characteristics, and there is evidence that that they are parallel to the three thunderbolt deities (Huracan, Youngest Thunderbolt, and Sudden Thunderbolt) who play a central role in the creation story found in the Popol Vuh (Bassie-Sweet 2008:102–124). When named together, Youngest Thunderbolt is always in the second position, like GII. Maya hearths are composed of three large stones that contain the fire and support the cooking vessels. There is evidence that the three hearthstones were thought to be manifestations of the three thunderbolt deities GI, GII, and GIII (Bassie-Sweet 2008:63, 121–122).

The Palenque Cross Group is composed of a plaza with a small platform at its center and a temple-pyramid on its north, west, and east sides (Temple of the Cross, Temple of the Sun, and Temple of the Foliated Cross). The inscriptions of these temple-pyramids indicate that each building was dedicated to one member of the thunderbolt triad (GI-TC, GIII-TS, and GII-TFC). Each temple-pyramid has a wall panel on the back wall of its inner sanctuary, and these three panels form a continuous narrative beginning with the north panel (Tablet of the Cross), continuing on the west panel (Tablet of the Sun), and ending on the east panel (Tablet of the Foliated Cross). This reading order follows the birth order of these three deities (see chapter 8 for further discussion). Each panel and temple is nicknamed after the central icon of its respective sanctuary panel. The Tablet of the Cross is so named because its central icon is a cross-shaped tree. The central icon of the Tablet of the Foliated Cross also has a cross-shape, but it is a stylized corn plant with twin ears of corn. The icon on the Tablet of the Sun includes a shield emblazed with the face of GIII, who has facial characteristics similar to the sun god.

Figure 1.1. Dumbarton Oaks Tablet, drawing by Linda Schele, courtesy David Schele.

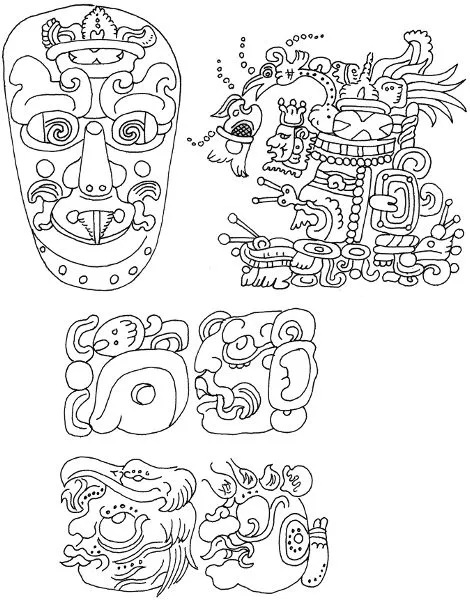

The Thunderbolt Deity GI

The deity GI is an anthropomorphic god with a Roman nose who wears a Chahk earring, and his name is most often represented by a portrait glyph of him wearing the Chahk earring (figure 1.2). An expanded version of his full name phrase on the Palenque Creation Tablet demonstrates that his name includes the word chahk (Bassie-Sweet 2008:111). The first glyph is a portrait of GI wearing a headdress in the form of a fish-eating water bird. Such birds are intimately associated with him, and it is likely that this is an avian manifestation of GI. This portrait of GI does not wear the Chahk earring, but the second glyph in this nominal phrase is a portrait of Chahk. Although the portrait glyph of GI has yet to be deciphered, this example demonstrates that his name ended in the word Chahk, and consequently it must be concluded that GI was a thunderbolt god. Many of the storms that descend on the Maya region come from the north, and given GI’s association with north, it has been argued that he was a Chahk specifically associated with northern storms (Bassie-Sweet 2008:109–113). Furthermore, GI’s eye is frequently depicted as a swirl similar to swirls used to depict turbulent water, a highly appropriate eye for a storm god.

Numerous examples of GI illustrate him wearing a headdress in the form of the so-called Quadripartite Badge motif, and the narrative on the Temple of the Inscriptions panels specifically states that the Quadripartite Badge was the headdress of GI. The main element of the Quadripartite Badge motif is a bowl marked with a k’in sign that typically contains three objects: a Spondylus shell, an upright stingray spine, and an element infixed with a crossed band (Robertson 1974). The bowl is often illustrated as a skeletal zoomorphic creature. The k’in bowl itself is found in contexts that indicate it was used for burning offerings including incense, blood, and hearts (Stuart 1998:389–390; 2005a:168; Stuart and Stuart 2008:175; Taube 1998, 2009). The stingray spine in the k’in bowl was an instrument used by Maya as a perforator during bloodletting rites (Joralemon 1974). Hellmuth (1987) noted that Early Classic depictions of the Quadripartite Badge illustrate the tooth of a shark in place of the typical Late Classic stingray spine. Many portraits of GI have a shark’s tooth for an incisor. The implication is that these marine bloodletters were thought to be a manifestation of GI. The Spondylus shell pictured in the k’in bowl is also identified with blood offerings and thunderbolt gods. Such shells have been found in burials and caches, and they were often used as receptacles for blood offerings. As noted above, a Spondylus shell serves as the pars pro toto for the word chahk “thunderbolt.”

Figure 1.2. The deity GI.

The Quadripartite Badge motif is occasionally held by rulers as a scepter, such as on the Tablet of the Cross, the Temple of the Cross jambs, and House D, Pier C. In these two former examples, liquid pours from the mouth of the zoomorphic creature. Although such liquid is oft...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 The Creator Grandparents and the Place of Duality

- Chapter 2 The Family of the Creator Grandparents and Complementary Opposition

- Chapter 3 The Calendar and the Narrative Time Frame

- Chapter 4 The Literary Nature of Mayan Texts, Ancient and Modern

- Chapter 5 Text and Image

- Chapter 6 The Palenque Tablet of the 96 Glyphs

- Chapter 7 The Narrative of the Palenque Temple of the Inscriptions Sarcophagus

- Chapter 8 The Palenque Cross Group Narrative

- Chapter 9 Conclusions

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Maya Narrative Arts by Karen Bassie-Sweet,Nicholas A. Hopkins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.