- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

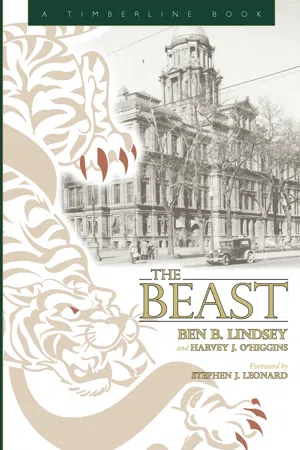

The Beast

About this book

Judge Benjamin Barr Lindsey's exposé of big business's influence on Colorado and Denver politics, a best seller when it was originally published in 1911, is now back in print. The Beast reveals the plight of working-class Denver citizens—in particular those Denver youths who ended up in Lindsey's court day after day. These encounters led him to create the juvenile court, one of the first courts in the country set up to deal specifically with young delinquents. In addition, Lindsey exposes the darker side of many well-known figures in Colorado history, including Mayor Robert W. Speer, Governor Henry Augustus Buchtel, Will Evans, and many others. When first published, The Beast was considered every bit the equal Upton Sinclair's The Jungle and sold over 500,000 copies. More than just a fascinating slice of Denver history, this book—and Lindsey's court— offered widespread social change in the United States.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER I

FINDING THE CAT

I CAME TO DENVER in the spring of 1880, at the age of eleven, as mildly inoffensive a small boy as ever left a farm—undersized and weakly, so that at the age of seventeen I commonly passed as twelve, and so unaccustomed to the sight of buildings that I thought the five-story Windsor Hotel a miracle of height and magnificence. I had been living with my maternal grandfather and aunt on a farm in Jackson, Tennessee, where I had been born; and I had come with my younger brother to join my parents, who had finally decided that Denver was to be their permanent home. The conductors on the trains had taken care of us, because my father was a railroad man, at the head of the telegraph system; and we had been entertained on the way by the stories of an old forty-niner, with a gray moustache, who told us how he had shot buffalo on those prairies where we now saw only antelope. I was not precocious; his stories interested me more than anything else on the journey; and I stared so hard at the old pioneer that I should recognize him now, I believe, if I saw him on the street.

My schooling was not peculiar; there was nothing “holier than thou” In my bringing up. My father, being a Roman Catholic convert from the Episcopalian Church, sent me to Notre Dame, Indiana, to be educated; and there, to be sure, I read the “Lives of the Saints,” aspired to be a saint, and put pebbles in my small shoes to “mortify the flesh,” because I was told that a good priest, Father Hudson—whom I all but worshipped—used to do so. But even at Notre Dame, and much more in Denver, I was homesick for the farm; and at last I was allowed to return to Jackson to be cared for by my Protestant relatives. They sent me to a Baptist school till I was seventeen. And when I was recalled to Denver, because of the failure of my father’s health, I went to work to help earn for the household, with no strong attachment for any Church and with no recognized membership in any.

I suppose there is no one who does not look back upon his past and wonder what he should have become in life if this or that crucial event had not occurred to set his destiny. It seems to me that if it had not been for the sudden death of my father I, too, might have found our jungle beast a domestic tabby, and have fed it its prey without realizing what I was about. I should have been a lawyer, I know; for I had had that ambition from my earliest boyhood, and I had been confirmed in it by my success in debating at school. (Once, at Notre Dame, I spoke for a full hour in successful defence of the proposition that Colorado was the “greatest state in the Union,” and proved at least that I had a lawyer’s “Wind.”) But I should probably have been a lawyer who has learned his pleasant theories of life in the colleges. And on the night that my father died, the crushing realities of poverty put out an awful and compelling hand on me, and my struggle with them began.

I was eighteen years old, the eldest of four children. I had been “Writing proofs” In the Denver land office, for claimants who had filed on Government land; and I had saved $150 of my salary before my work there ceased. I found, after my father’s death, that this $150 was all we had in the world, and $130 of it went for funeral expenses. His life had been insured for $15,000, and we believed that the premiums had all been paid, but we could not find the last receipt; the agent denied having received the payment; the policy had lapsed on the day before my father’s death; and we got nothing. Our furniture had been mortgaged; we were allowed only enough of it to furnish a little house on Santa Fé Avenue; and later we moved to a cottage on lower West Colfax Avenue, in which Negroes have since lived.

I went to work at a salary of $10 a month, in a real estate office—as office boy—and carried a “route” of newspapers in the morning before the office opened, and did janitor work at night when it closed. After a month of that, I got a better place, as office boy, with a mining company, at a salary of $25 a month. And finally, my younger brother found work in a law office and I “swapped jobs” with him—because I wished to study law!

It was the office of Mr. R. D. Thompson, who still practises in Denver; and his example as an incorruptibly honest lawyer has been one of the best and strongest influences of my life.

I had that one ambition—to be a lawyer. Associated with it I seem to have had an unusual curiosity about politics. And where I got either the ambition or the curiosity, I have no idea. My father’s mother was a Greenleaf,* and related to the author of “Greenleaf on Evidence,” but my father himself had nothing of the legal mind. As a boy, living in Mississippi, he had joined the Confederate army when he was preparing for the University of Virginia, had attained the rank of captain, had become General Forrest’s private secretary, and had writ-ten—or largely helped to write—General Forrest’s autobiography. He was idealistic, enthusiastic, of an inventive genius, with a really remarkable command of English, and an absorbing love of books. My mother’s father was a Barr, from the north of Ireland, a Scotch-Irish Presbyterian; her mother was a Woodfalk of Jackson County, Tennessee, a Methodist. The members of the family were practical, strong-willed, able men and women, but with no bent, that I know of, toward either law or politics.

And yet, one of the most vivid memories of my childhood in Jackson is of attending a political rally with my grandfather and hearing a Civil War veteran declaim against Republicans who “Waved the bloody shirt”—a memory so strong that for years afterward I never saw a Republican without expecting to see the gory shirt on his back, and wondering vaguely why he was not in jail. When I came to Denver, where the Republicans were dominant, I felt myself in the land of the enemy. And when I “swapped” myself into Mr. Thompson’s office, I was surprised to find that my employer, though a Republican from Pittsburg, was so human that one of the first things he did was to give me a suit of clothes. If there is anything more ridiculously dangerous than to blind a child’s mind with such prejudices, I do not know what it is.

However, my own observations of what was going on about me were already opening my eyes. I had read, in the newspapers, of how the Denver Republicans won the elections by fraud—by ballot-box stuffing and what not—and I had followed one “Soapy” Smith on the streets, from precinct to precinct, with his gang of election thieves, and had seen them vote not once but five times openly. I had seen a young man, whom I knew, knocked down and arrested for “raising a disturbance” when he objected to “Soapy” Smith’s proceeding; and the policeman who arrested him did it with a smile and a wink. When I came to Mr. Thompson to ask him how he, a Republican, could countenance such things, he assured me that much of what I had been reading and hearing of election frauds was a lie—the mere “Whine” of the defeated party—and I saw that he believed what he said. I knew that he was an honest, upright man; and I was puzzled. What puzzled me still more was this: although the ministers in the Churches and “prominent citizens” In all walks of life denounced the “election crooks” with the most laudable fervour, the election returns showed that the best people in the Churches joined the worst people in the dives to vote the same ticket, and vote it “straight.” And I was most of all puzzled to find that when the elections were over, the opposition newspaper ceased its scolding, the voice of ministerial denunciation died away, and the crimes of the election thieves were condoned and forgotten.

I was puzzled. I saw the jungle of vice and party prejudice, but I did not yet see “The Cat.” I saw its ears and its eyes there in the underbrush, but I did not know what they were. I thought they were connected with the Republican party.

And then I came upon some more of the brute’s anatomy. Members of the Legislature in Denver were accused of fraud in the purchase of state supplies, and—some months later—members of the city government were accused of committing similar frauds with the aid of civic officials and prominent business men. It was proved in court, for example, that bills for $3 had been raised to $300, that $200 had been paid for a bundle of hay worth $8, and $50 for a yard of cheesecloth worth five cents; barrels of ink had been bought for each legislator, though a pint would have sufficed; and an official of the Police Department was found guilty of conniving with a gambler named “Jim” Marshall to rob an express train. I watched the cases in court. I applauded at the meetings of leading citizens who denounced the grafters and passed resolutions in support of the candidates of the opposition party. I waited to see the criminals punished. And they were not punished. Their crimes were not denied. They were publicly denounced by the courts and by the investigating committees, but somehow, for reasons not clear, they all went scot-free, on appeals. Some mysterious power protected them, and I, in the boyish ardour of my ignorance, concluded that they were protected by the Republican “bloody shirt”—and I rushed into that (to me) great confederation of righteousness and all-decent government, the Democratic party.

It would be laughable to me now, if it were not so “sort of sad.”

Meanwhile, I was busy about the office, copying letters, running errands, carrying books to and from the court rooms, reading law in the intervals, and at night scrubbing the floors. I was pale, thin, bigheaded, with the body of an underfed child, and an ambition that kept me up half the night with Von Holst’s “Constitutional Law,” Walker’s “American Law,” or a sheepskin volume of Lawson’s “Leading Cases in Equity.” I was so mad to save every penny I could earn that instead of buying myself food for luncheon, I ate molasses and gingerbread that all but turned my stomach; and I was so eager to learn my law that I did not take my sleep when I could get it. The result was that I was stupid at my tasks, moody, melancholy, and so sensitive that my employer’s natural dissatisfaction with my work put me into agonies of shame and despair of myself. I became, as the boys say, “dopy.” I remember that one night, after I had scrubbed the floors of our offices, I took off the old trousers in which I had been working, hung them in a closet, and started home; and it was not until the cold wind struck my bare knees that I realized I was on the street in my shirt. Often, when I was given a brief to work up for Mr. Thompson, I would slave over it until the small hours of the morning and then, to his disgust—and my unspeakable mortification—find that my work was valueless, that I had not seized the fundamental points of the case, or that I had built all my arguments on some misapprehension of the law.

Worse than that, I was unhappy at home. Poverty was fraying us all out. If it was not exactly brutalizing us, it was warping us, breaking our healths and ruining our dispositions. My good mother—married out of a beautiful Southern home where she had lived a life that (as I remembered it) was all horseback rides and Negro servants—had started out bravely in this debasing existence in a shanty, but it was wearing her out. She was passing through a critical period of her life, and she had no care, no comforts. I have often since been ashamed of myself that I did not sympathize with her and understand her, but I was too young to understand, and too miserable myself to sympathize. It seemed to me that my life was not worth living—that every one had lost faith in me—that I should never succeed in the law or anything else—that I had no brains—that I should never do anything but scrub floors and run messages. And after a day that had been more than usually discouraging in the office and an evening of exasperated misery at home, I got a revolver and some cartridges, locked myself in my room, confronted myself desperately in the mirror, put the muzzle of the loaded pistol to my temple, and pulled the trigger.

The hammer snapped sharply on the cartridge; a great wave of horror and revulsion swept over me in a rush of blood to my head, and I dropped the revolver on the floor and threw myself on my bed.

By some miracle the cartridge had not exploded; but the nervous shock of that instant when I felt the trigger yield and the muzzle rap against my forehead with the impact of the hammer—that shock was almost as great as a very bullet in the brain. I realized my folly, my weakness; and I went back to my life with something of a man’s determination to crush the circumstances that had almost crushed me.

Why do I tell that? Because there are so many people in the world who believe that poverty is not sensitive, that the ill-fed, overworked boy of the slums is as callous as he seems dull. Because so many people believe that the weak and desperate boy can never be anything but a weak and vicious man. Because I came out of that morbid period of adolescence with a sympathy for children that helped to make possible one of the first courts established in America for the protection as well as the correction of children. Because I was never afterward as afraid of anything as of my own weakness, my own cowardice—so that when the agents of the Beast in the courts and in politics threatened me with all the abominations of their rage if I did not commit moral suicide for them, my fear of yielding to them was so great that I attacked them more desperately than ever.

It was about this time, too, that I first saw the teeth and the claws of our metaphorical man-eater. That was during the conflict between Governor Waite and the Fire and Police Board of Denver. He had the appointment and removal of the members of this Board, under the law, and when they refused to close the public gambling houses and otherwise enforce the laws against vice in Denver, he read them out of office. They refused to go, and defied him, with the police at their backs. He threatened to call out the militia and drive them from the City Hall. The whole town was in an uproar.

One night, in the previous summer, I had followed the excited crowds to Coliseum Hall to hear the Governor speak, and I had seen him rise like some old Hebrew prophet, with his long white beard and patriarchal head of hair, and denounce iniquity and political injustice and the oppressions of the predatory rich. He appealed to the Bible in a calm prediction that, if the reign of lawlessness did not cease, in time to come “blood would flow in the land even unto the horses’ bridles.” (And he earned for himself, thereby, the nickname of “Bloody Bridles” Waite.)

Now it began to appear that his prediction was about to come true; for he called out the militia, and the Board armed the police. My brother was a militiaman, and I kept pace with him as his regiment marched from the Armouries to attack the City Hall. There were riflemen on the towers and in the windows of that building; and on the roofs of the houses for blocks around were sharpshooters and armed gamblers and the defiant agents of the powers who were behind the Police Board in their fight. Gatling guns were rushed through the streets; cannon were trained on the City Hall; the long lines of militia were drawn up before the building; and amid the excited tumult of the mob and the eleventh-hour conferences of the Committee of Public Safety, and the hurry of mounted officers and the marching of troops, we all waited with our hearts in our mouths for the report of the first shot. Suddenly, in the silence that expected the storm, we heard the sound of bugles from the direction of the railroad station, and at the head of another army—a body of Federal soldiers ordered from Fort Logan by President Cleveland, at the frantic call of the Committee of Public Safety—a mounted officer rode between the lines of militia and police, and in the name of the President commanded peace.

The militia withdrew. The crowds dispersed. The police and their partisans put up their guns, and the Beast, still defiant, went back sullenly to cover. Not until the Supreme Court had decided that Governor Waite had the right and the power to unseat the Board—not till then was the City Hall surrendered; and even so, at the next election (The Beast turning polecat), “Bloody Bridles” Waite was defeated after a campaign of lies, ridicule, and abuse, and the men whom he had opposed were returned to office.

I had eyes, but I did not see. I thought the whole quarrel was a personal matter between the Police Board and Governor Waite, who seemed determined merely to show them that he was master; and if my young brother had been shot down by a policeman that night, I suppose I should have joined in the curses upon poor old “Bloody Bridles.”

However, my prospects in the office had begun to improve. I had had my salary raised, and I had ceased doing janitor work. I had become more of a clerk and less of an office boy. A number of us “kids” had got up a moot court, rented a room to meet in, and finally obtained the use of another room in the old Denver University building, where, in the gaslight, we used to hold “quiz classes” and defend imaginary cases. (That, by the way, was the beginning of the Denver University Law School.) I read my Blackstone, Kent, Parsons—working night and day—and I began really to get some sort of “grasp of the law.” Long before I had passed my examinations and been called to the bar, Mr. Thompson would give me demurrers to argue in court; and, having been told that I had only a pretty poor sort of legal mind, I worked twice as hard to make up for my deficiencies. I argued my first case, a damage suit, when I was nineteen. And at last there happened one of those lucky turns common in jury cases, and it set me on my feet.

A man had been held by the law on several counts of obtaining goods under false pretences. He had been tried on the first count by an assistant District Attorney, and the jury had acquitted him. He had been tried on the second count by another assistant, who was one of our great criminal lawyers, and the jury had disagreed. There was a debate as to whether it was worth while to try him for a third time, and I proposed that I should take the case, since I had been working on it and thought there was still a chance of convicting him. They let me have my way, and though the evidence in the third charge was the same as before—except as to the person defrauded—the jury, by good luck, found against him. It was the turning point in my struggle. It gave me confidence in myself; and it taught me never to give up.

And now I began to come upon “The Cat” again.

I knew a lad named Smith, whom I considered a victim of malpractice at the hands of a Denver surgeon whose brother was at the head of one of the great smelter companies of Colorado. The boy had suffered a fracture of the thigh-bone, and the surgeon—because of a hasty and ill-considered diagnosis, I believed—had treated him for a bruised hip. The surgeon, when I told him that the boy was entitled to damages, called me a blackmailer—and that was enough. I forced the case to trial.

I had resigned my clerkship and gone into partnership with a fine young fellow whom I shall call Charles Gardener*—though that was not his name—and this was to be our first case. We were opposed by Charles J. Hughes, Jr., the ablest corporation lawyer in the state; and I was puzzled to find the officers of the gas company and a crowd of prominent business men in court when the case was argued on a motion to dismiss it. The judge refused the motion, and for so doing—as he afterward told me himself—he was “cut” In his Club by the men whose presence in the court had puzzled me. After a three weeks’ trial, in which we worked night and day for the plaintiff—with X-ray photographs and medical testimony and fractured bones boiled out over night in the medical school where I prepared them—the jury stood eleven to one in our favour, and the case had to be begun all over again. The second time, after another trial of three weeks, the jury “hung” again, but we did not give up. It had been all fun for us—and for the town. The word had gone about the streets: “Go up and see those two kids fighting the corporation heavyweights. It’s more fun than a circus.” And we were confident that we could win; we knew that we were right.

One evening after dinner, when we were sitting in the dingy little back room on Champa Street that served us as an office, A. M. Stevenson—“Big Steve”—politician and attorney for the Denver City Tramway Company, came shouldering in to see...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- NOTE

- CONTENTS

- Foreword

- Introduction

- The Beast

- Chapter I Finding the Cat

- Chapter II The Cat Purrs

- Chapter III The Cat Keeps on Purring

- Chapter IV The Beast in the Democracy

- Chapter V The Beast in the County Court

- Chapter VI The Beast and the Children

- Chapter VII The Beast, Graft and Business

- Chapter VIII At work with the Children

- Chapter IX The Beast and the Ballot

- Chapter X The Beast and the Ballot (Continued)

- Chapter XI The Beast at Bay

- Chapter XII The Beast and the Supreme Court

- Chapter XIII The Beast and Reform

- Chapter XIV A City Pillaged

- Chapter XV The Beast, The Church and the Governorship

- Chapter XVI Hunting the Beast

- Chapter XVII A Victory at last

- Chapter XVIII Conclusion

- Index

- Footnotes

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Beast by Benjamin B. Lindsey,Harvey J. O'Higgins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.