![]()

1

The Greater Utatlán Project

A Constituted Community of a Late Postclassic Maya Capital

Hernando Cortes with his small army and native Indian allies conquered the Aztec in AD 1521, after which he received delegations from the indigenous groups in the Mayan regions. Cortes wrote to inform Emperor Charles V that he had sent Spanish and native delegates to the Pacific coastal areas 200 leagues distant from Tenochtitlán to learn about the towns of which he had heard, towns called Uclaclan and Guatemala (Mackie 1924: 12). The representatives returned to Cortes with more than 100 inhabitants of those cities, who, Cortes reports, pledged loyalty to the emperor. Thereafter, however, word was received that the Mayan natives were “molesting the towns of Soconusco” on the Pacific coast (Mackie 1924: 13). Pedro Alvarado was dispatched to the area at the end of AD 1523, with 120 horsemen, 300 foot soldiers (including crossbowmen and musketeers), and four pieces of artillery, accompanied by native allies (Mackie 1924: 14). It is from Alvarado’s expedition that we receive our first descriptions of the city and environs of Uclaclan, which Alvarado called Utlatan and we now call Utatlán or Q’umarkaj.

And they agreed to send and tell us that they gave obedience to our Lord the Emperor, so that I should enter the city of Utlatan, where they afterwards brought me, thinking that they would lodge me there, and then when thus encamped, they would set fire to the town some night and burn us all in it, without the possibility of resistance. And in truth their evil plan would have come to pass but that God our Lord did not see good that these infidels should be victorious over us, and there are only two ways of entering it; one of over thirty steep stone steps and the other by a causeway made by hand, much of which was already cut away, so that that night they might finish cutting it, and no horse could then have escaped into the country. As the city is very closely built and the streets very narrow, we could not have stood it in any way without either suffocating or else falling headlong from the rocks when fleeing from the fire. And as we rode up and I could see how large the stronghold was, and that within it we could not avail ourselves of the horses because the streets were so narrow and walled in, I determined at once to clear out of it on to the plain, although the chiefs of the town asked me not to do so, and invited me to seat myself and eat before I departed, so as to gain time to carry our their plans. (Alvarado 1924: 60–61)

We have other early descriptions of the town and environs of Q’umarkaj, including that of Francisco Antonio Fuentes y Guzman from about AD 1690, which was reproduced by Domingo Juarros (1823: 86–89) before making its way into A. P. Maudslay’s Biologia Centrali-Americana (Maudslay 1889–1902, 2: 34–35). Though Maudslay comments on the unreliability of the Fuentes y Guzman description (1889–1902, 2: 37), it is clear that both authors considered the city to be the ceremonial center and associated ruins on the plateau of Q’umarkaj. The description by Fuentes y Guzman is thus:

It was surrounded by a deep ravine that formed a natural fosse, leaving only two very narrow roads as entrances to the city, both of which were so well defended by the castle of Resguardo, as to render it impregnable. The center of the city was occupied by the royal palace, which was surrounded by the houses of the nobility; the extremities were inhabited by the plebeians. (Maudslay 1889–1902, 2: 34)

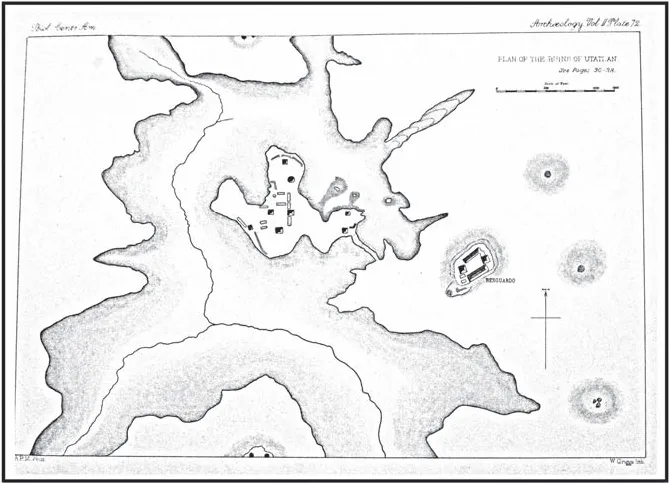

When Maudslay visited Utatlán in January 1887 he surveyed the ruins, and his sketch map of the site, reproduced here as Figure 1.1, shows the principal structures at the epicenter of Q’umarkaj. It is the task of this volume to more fully and accurately describe the residential zone, which is not depicted on the map or described in his text. It is important to understand this residence zone so that we may also understand the organization and composition of the city that was the K’iche’ capital in the Late Postclassic Mayan world, a city only briefly described by the Spanish conquistadors. The city is presumed to be more than the elite center described by Fuentes y Guzman, and by Alvarado before him, and more than what was mapped by Maudslay. We will use archaeological data to describe the community of Utatlán as perceived by its contemporaneous citizens, an attempt at an emic understanding of the ceremonial center and residence zone that formed the political center of the K’iche’ Maya. The evidence for social stratification, craft specialization, external trade, both elite and commoner residences, and the characteristics of the defensive perimeter for the site will be presented. It will be argued that specific archaeological findings support the conclusion that this proposed Utatlán was a unitary community perceived by the K’iche’ (an emic construct), even though this character was not recognized by the Spaniards (an etic construct).

1.1. Plan of the ruins of Utatlán from Maudslay’s Archaeologia, Biología Centrali-Americana, plate 52 (photographed by author, used with permission from the Museum Library, University of Pennsylvania)

My focus will be on Q’umarkaj and its supporting residence zone and will not preclude other emically valid constructs of the political and social organization of highland Guatemala and the K’iche’ state. That is to say, community can be broadly understood to have multiple levels. A description of how one might perceive some of the multiple communities that could be established for a hypothetical K’iche’ resident would place him or her within the boundaries of the city of Utatlán as a resident of a specific ward or subdivision of that city, as a member of a lineage-based or otherwise constituted chinamit (Carmack 1981: 164–165; see also Braswell 2003a), and as a member of a K’iche’ lineage or a vassal/dependent subject of a member of the lineage (Carmack 1981: 148ff), with economic interests of obligations related to a kalpul or territorial subdivision of the K’iche’ realm (Weeks 1980: 30–34) that was in the ajawarem of the Nima K’iche rather than of the Ilocab’ (Chisalin) or Tamub’ (Pismachi) (Carmack 1981: 166–180; Weeks 1980: 37–40).

ETHNOHISTORIC FOUNDATIONS FOR THE GREATER UTATLÁN PROJECT

Robert Carmack of the State University of New York (SUNY) at Albany has devoted much of his professional career to studying the ethnography, ethnohis-tory, linguistics, and archaeology of the K’iche’ Maya of Guatemala (Carmack 1977, 1981; Carmack and Weeks 1981). The K’iche’ played a prominent role in the history of Central America. They were a dominant force in the region when the Spaniards came as conquerors. The K’iche’, and their neighbors, were literate before the conquest and passed on to us their mythology and history written in their own words, transcribed in their own language using a European alphabet. These provide details on their religious and cultural beliefs, their migrations to the Guatemala highlands, and their political and social organization prior to the arrival of the Spaniards (Carmack 1981; Edmonson 1971).

These native accounts, which may relate their mythology and history before the conquest, may also validate their landholdings and social position so that these could be maintained following imposition of Spanish rule. Florescano (2006), however, proposes that the manuscripts were originally created as national histories to preserve native lore and only later took on the role of legal titles. A cautionary note on interpretation of these native histories has also been raised (Christenson 1997; Sachse and Christenson 2005), that is, that we may not fully understand where mythology ends and history begins within these sources if we neglect to consider their original purpose. The apparent early stages of the history may, in fact, be metaphorical references to mythic figures and locations.

The ethnohistoric sources, although generally dating to the early post-conquest period in their original form, have been translated and discussed over the years. During the intervening times, orthographic conventions for transcribing K’iche’ terms have not been constant or consistent. What was previously referred to as the Quiché people and language is now referred to as K’iche’, and the spelling conventions used in most of the references cited in this report have evolved. These have now been standardized by the Academia de Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala (ALMG) (Jiménez 1998: 5). An effort herein is made to use a format and spelling that are consistent with ALMG throughout, rather than a mixture of recent formats for some words and earlier customs for others. The exception to this rule of deferring to the ALMG is that when a passage is cited directly from a text, the spelling conventions of the source will be followed and the passage will appear in quotation marks or in an offset position. Also, where a modern place-name for a community or geographic region is referred to, the customary usage will be retained; for example, Utatlán lies in the Quiche Basin near the modern city of Santa Cruz del Quiché, capital of the Department of Quiché.

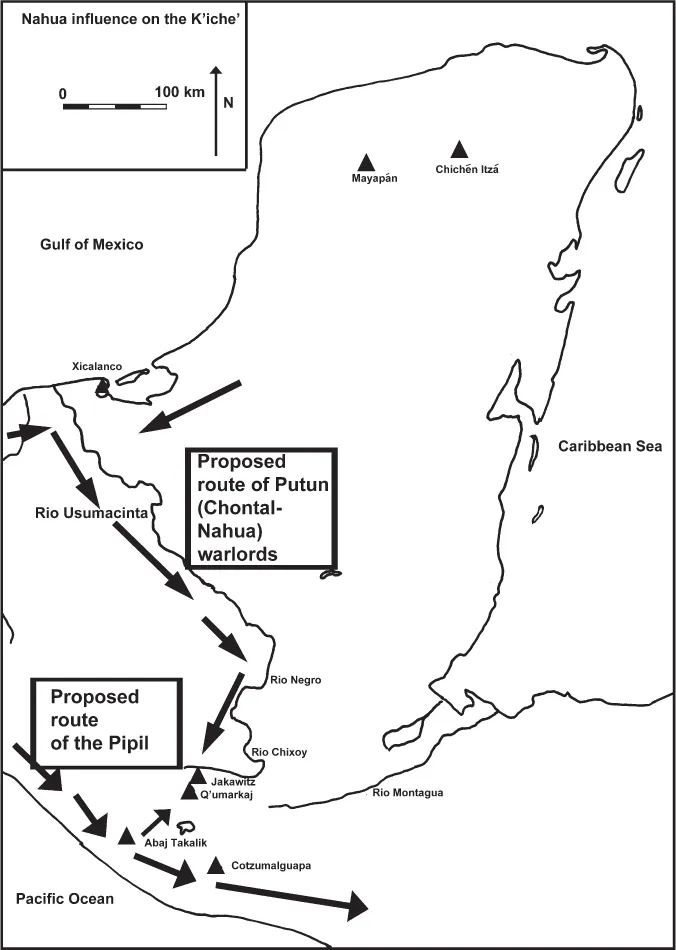

According to historical reconstruction presented by Carmack (1981: 44–50), the residents of Utatlán were an amalgam of indigenous K’iche’ speakers whose dialect developed within the Guatemala highlands and descendants of Chontal-Nahua-speaking warlords who migrated from the lowlands of the Gulf coastal Tabasco-Veracruz area of Mexico. The migration of the warlords coincided with the collapse of the Yucatán Maya center of Chichén Itzá that is generally thought to have occurred around AD 1200. Andrews, Andrews, and Castellanos (2003), however, place the fall of Chichén Itzá in the eleventh century rather than the thirteenth century. The Chontal-Nahua warlords came to the region of Utatlán by following the Rio Usumacinta drainage to the Verapaz highlands near San Pedro Carchá and then continuing along the Rio Negro and Rio Agua Caliente to the San Andres Basin, ultimately crossing through the mountains to establish the early K’iche’ centers near Santa Rosa Chujuyup (Map 1.1). These emigrants were few in number and had tightly organized lineages. They are described as mobile and military, mostly male, who intermarried with the local K’iche’ population and adopted the local language (Carmack 1981).

The origins of the K’iche’ elite are far from settled, but in his reconstruction Carmack (1981) placed the arrival of Chontal-Nahua warlords in the Quiche Basin at AD 1225. The date was established by working backward from the known date of the conquest of Utatlán by Pedro de Alvarado in AD 1524, and he used a chronology of dynastic succession from ethnohistoric sources that preserved not only the account of the movement into the Guatemala highlands but also a dynastic succession of rulers that could be followed back to that arrival (see Table 1.1). The sources researched by Carmack and others include the Popol Wuj (also spelled Popol Vuh), the mythology and history of the K’iche’ Maya of Utatlán (Edmonson 1971; Recinos, Goetz, and Morley 1950); the Annals of the Cakchiquels (Brinton 1885; Goetz and Recinos 1974); the Titles of the Lords of Totonicapan or Titulo Totonicapan (Chonay and Goetz 1974); as well as numerous native chronicles or titulos examined by Carmack. The chronology was based on a generational length of twenty-five years spanning eleven reigns between the arrival of the first ruler, B’alam Kitze, and the conquest by Alvarado in 1524. One ruler, K’iq’ab’, was granted fifty years. The founding of Utatlán by Carmack’s calculation would be approximately AD 1400.

Wauchope (1970: 241–241) discussed the pitfalls of establishing a chronology based on the ethnohistoric sources. Aside from inconsistencies in various lists of rulers, even within a single text, generation length could be calculated as anywhere from twenty years to forty years. Father-son relationships might be separated by a reign. In his discussion, he notes that others estimated the city was established between AD 1125 and 1275 (Brasseur de Bourbourg), between AD 1214 and 1254 (Villacorta 1938: 125, 142; Ximenez 1929: 71), in the twelfth century (Lothrop 1933: 111), or in the fifteenth century (Brinton 1885: 59). Wauchope used father-son relationships stated or implied in the sources and a generational length of twenty years to place the arrival of the warlords in the Quiche Basin at ca. AD 1263 and the founding of Utatlán at AD 1433. Elsewhere (Wauchope 1947) he elaborates further on the problems of correlating pre-conquest chronology and the Mayan calendar with the European calendar and post-contact events based on assumptions of generation spans that might range between eighteen and fifty-five years and that could lead to the founding of Q’umarkaj at an earliest date of AD 1217 and a latest date of AD 1490, each of which, he maintained, presented very unlikely scenarios regarding the life events of K’iche’ rulers. The three early K’iche’ rulers who, documents report, were sent to receive the symbols of authority could have been born, according to the possible scenarios, as early as AD 977 or as late as AD 1343, but Wauchope opts for a “more probable” AD 1210 (1947: 64).

MAP 1.1. Map of possible routes of Nahua influence on the K’iche’ (data from Carmack 1981 and Van Akkeren 2009; from Carmack 1968; redrawn by author)

TABLE 1.1. Chronological list of K’iche’ rulers

Dates (AD) | Name |

1225-1250 | B’alam Kitze |

1250-1275 | K’ok’oja |

1275-1300 | E,Tz’ikim |

1300-1325 | Ajkan |

1325-1350 | K’okaib’ |

1350-1375 | K’onache |

1375-1400 | K’otuja |

1400-1425 | Quq’kumatz |

1425-1475 | K’iq’ab’ |

1475-1500 | Vahxak’ iKaam |

1500-1524 | Oxib Kej |

Source: after Carmack 1981: 122. |

An alternative hypothesis has bee...