eBook - ePub

Enduring Legacies

Ethnic Histories and Cultures of Colorado

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Enduring Legacies

Ethnic Histories and Cultures of Colorado

About this book

Traditional accounts of Colorado's history often reflect an Anglocentric perspective that begins with the 1859 Pikes Peak Gold Rush and Colorado's establishment as a state in 1876. Enduring Legacies expands the study of Colorado's past and present by adopting a borderlands perspective that emphasizes the multiplicity of peoples who have inhabited this region.

Addressing the dearth of scholarship on the varied communities within Colorado-a zone in which collisions structured by forces of race, nation, class, gender, and sexuality inevitably lead to the transformation of cultures and the emergence of new identities-this volume is the first to bring together comparative scholarship on historical and contemporary issues that span groups from Chicanas and Chicanos to African Americans to Asian Americans.

This book will be relevant to students, academics, and general readers interested in Colorado history and ethnic studies.

Addressing the dearth of scholarship on the varied communities within Colorado-a zone in which collisions structured by forces of race, nation, class, gender, and sexuality inevitably lead to the transformation of cultures and the emergence of new identities-this volume is the first to bring together comparative scholarship on historical and contemporary issues that span groups from Chicanas and Chicanos to African Americans to Asian Americans.

This book will be relevant to students, academics, and general readers interested in Colorado history and ethnic studies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Enduring Legacies by Arturo J. Aldama, Elisa Facio, Daryl Maeda, Reiland Rabaka, Arturo J. Aldama,Elisa Facio,Daryl Maeda,Reiland Rabaka in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

University Press of ColoradoYear

2010Print ISBN

9781607320500, 9781607320494eBook ISBN

9781607320517PART I

Early Struggles

1 Pictorial Narratives of San Luis, Colorado:

Legacy, Place, and Politics

So, anyway I created that [embroidery of La Sierra]. It was more of a contemporary kind of thing, but it was history. And I thought, “If I don’t get this down . . . now that it’s happening, somebody might not think of it as part of the historical documentation of the area.”

—JOSEPHINE LOBATO1

Traveling along State Highway 159 heading south to New Mexico, one passes through San Luis, locally acclaimed as the “Oldest Town in Colorado,” founded in 1851. At one of the main intersections in this small community is a mural—somewhat faded but still evocative of the community’s history and value system.2 Its themes represent local perceptions of the area’s legacy: the era of nomadic Indian tribes, a dynamic foreshortened view of the upper portion of the crucifix suspended in clouds from which Spanish conquistadors emerge, an allegorical rendering of the largesse of Mother Earth, and other panels depicting settlers, hunters, farmers, and scenes of adobe making. The mural’s prominent position advertises a symbolically constructed glimpse of the community’s belief system with respect to the primacy of Catholicism, ethnic heritage and pride, and a deep connectedness to the earth through hunting and agriculture. Among these various images, one of the most binding elements around which the San Luis community coheres is land—its constancy, its use, and the power exercised through its possession and maintenance. The links between the belief in land as a God-given birthright and the Spanish conquest of the region in the name of God and religion is apparent in the mural’s iconic arrangement of conquistadors, Christ, and cultivation.

This chapter investigates the local sense of place and heritage in San Luis through a study of ethnicity and the ways cultural identity is conceived and constructed. By analyzing the processes of place making and identifying the forces of cultural politics active in San Luis, we ask how “understandings of locality, community and region are formed and lived [in this particular place].”3 In addition, the notion of material culture as an objectification of cultural values and a group’s aesthetic system is considered basic to this inquiry. This discussion argues for the importance of material objects in the formation of personal and collective identities and demonstrates how this operates in terms of the creative work of a particular San Luis artist, Josephine Lobato. Lobato creates embroidered narratives about Hispanic life in the San Luis Valley using an innovative style derived from a traditional Spanish colonial textile technique known as colcha embroidery. Colcha, in its modified contemporary version as a stitched pictorial narrative (visual storytelling) linked to a historical creative practice, becomes a means to explore issues of colonial legacy and ancestral rights. Its mode of creation also relies on reflexivity as a form of artistic and meditative feedback flowing between art and life’s experiences. Thus an ethnographic examination of ethnicity and sense of place along with an art historical descriptive analysis take “culture” as the subject of investigation and work together to foreground a specific genre of artwork as critical to the interplay of aesthetic and socio-cultural interaction in San Luis.

San Luis is located in one of the most impoverished counties in Colorado, Costilla County. It is a place of contrast—rich in natural resources yet poor economically. It is also culturally distinct from other towns in the area. In recent years, when ethnic solidarity emerging in the face of historic Anglo dominance in this region has been invigorating self-esteem and community pride, the issues of land and birthright are crucial determinants of legitimacy. As broadcast through the imagery of the “civic” mural, in present-day San Luis the prevailing attitude identifies with a cultural legacy from Spain rather than Mexico. One year during the annual summer fiesta of Santana and Santiago, an older resident ardently informed me that San Luis townspeople label themselves as Spanish—not Latinos or Mexican Americans: “Somos españoles” (we are Spanish). The majority of San Luis residents use the terms “Hispano,” “Hispanic,” and “Spanish” interchangeably, with Hispanic the most frequent. Thus community members’ cultural and genealogical understanding of heritage (as publicly espoused to outsiders) honors the persistence of Spanish lineage apart from the vicissitudes of time and birthplace.

The anthropologist Clifford Geertz has written that ethnography is the discovery of a particular group’s perception of “who they think they are; what they think they are doing; and to what end they think they are doing it.” He goes on to say that the object of ethnography is to gain a familiarity with the “frames of meaning within which they enact their lives” (2000:16). A few of the discernible “frames of meaning” applicable to the ethos or worldview of San Luis residents are represented through the iconography and symbolism in Josephine Lobato’s colcha embroideries. These pertain to the salient notions of legacy, ancestral and communal rights, ethnicity, and religious faith. Furthermore, Lobato’s pictorial narratives provide a double-layered reading of human history and relationship in this community. One layer is concerned with the story and the recording of meaning. The other is more abstract and involves the synthesis of human action and interpretation viewed through the artist’s creativity and imagination. Artifacts, such as colcha embroideries, are containers of human histories, collective memories, and political relations as much as they are cultural and aesthetic properties of the environment. These more intangible properties are subject to the same dynamism that acts as a vector of cultural identity helping to shape the lives and consciousness of individuals living in particular places.

Visualization of stories is a complex process of translating words and concepts into images accompanied by the subsequent transformation of lines of verbal narrative into a symbolic rendering of the suggestive, the evocative, and the poetic. Memory stories shared among the people of San Luis are artistically expressed through Josie Lobato’s imagination. As pictorial narratives they become visual accounts of lives “lived.” They are created out of remembrance, which is part of an ongoing collective enterprise belonging to the entire community that is never finished. Each time people from the San Luis area look at Lobato’s colchas, they add their own reminiscences to the story lines, thus expanding the pieces’ power and inclusiveness. Not everyone, however, shares the exact same memories or interprets them in the same way. Within a community such as San Luis, the similarity of memories is based more on resemblance than on replication. Individual memories differ but align with group interests in recalling certain experiences that resemble or resonate with each other. These reminiscences are part of the collective memory patterns of a group and are thus recognized for their significance and commonality.

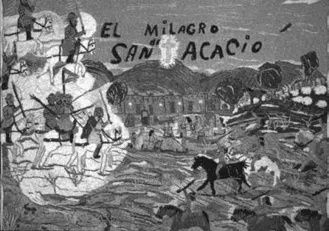

1.1. El Milagro de San Acacio, embroidery by Josephine Lobato, 1992. Permission granted by Lobato.

One of Josie Lobato’s early embroideries, El Milagro de San Acacio (1992), reveals how social memory and landscape implicate kin relations in light of a religious miracle. This folktale is widespread around the Southwest, but in this case it legitimates the founding of the San Acacio settlement near San Luis and the line of descent from the original settlers. Another colcha embroidery, La Sierra (1999), shows how memories of ancestral heritage, which are inscribed in the land, become the basis for upholding traditional, customary Spanish land rights in the face of outside wealth and power. The discussion that follows analyzes the imagery of these two pictorial narratives as representing native San Luis perceptions of the legacy and the right to not only be rooted in a certain place but to also be inseparable from that place.

El Milagro de San Acacio is inspired by a localized version of a folktale about the religious intervention and miraculous salvation of a mid–nineteenth-century settler community from being slaughtered by a band of Ute Indians. This settlement was eponymously named “San Acacio” in honor of the avenging patron saint. Enduring memories of these people’s religious faith along with the names of individual families still residing in the San Luis area constitute a legacy of kinship located in an inimical, unfriendly landscape and nurtured through generations of descendants as a sacred inheritance.

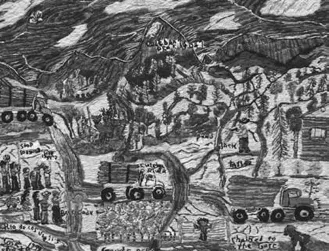

1.2. La Sierra, embroidery by Josephine Lobato, 1999. Permission granted by author.

La Sierra portrays a scene of a fairly recent political environmental protest staged in 1999 in the alpine meadows of a section of the traditional Spanish Land Grant, located in the mountains east of San Luis. The land grant was originally bestowed in the sixteenth century and was validated again in the nineteenth century when settlers were issued deeds to the land specifying rights for grazing and communal access to water, firewood, and timber. The people of San Luis view the history of the Spanish Land Grant as intertwined with issues of heritage and cultural autonomy that depend on the collective right to use resources (not necessarily “ownership” but the right to use). This arrangement is clearly stated in the 1863 Beaubien Deed, based on the original tenets of the Spanish Land Grant: “As such, everyone should exercise scrupulous care with the use of water without causing harm to their vecinos [neighbors] . . . nor to anyone; all of the inhabitants shall have the convenient arrangement, the enjoyment of the benefits of the pastures, the water, wood, and lumber, always being careful not to prejudice one another” (Sandoval 1985:22).

In 1960 a southern lumber baron named Jack Taylor privately purchased 77,750 acres belonging to this tract of land in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. He enclosed the land and fenced it off, thus making it inaccessible to Spanish descendants in San Luis who had been using the land for over 100 years. After almost three decades in the court system, communal grazing rights were reestablished in 2003 by a U.S. Supreme Court decision. La Sierra not only represents one scene in a long period of disenfranchisement but also celebrates the potency of collective memories of ancestral rights embedded in the landscape. This factor of memory as a viable mode of establishing ancestral authority was decisive in the 2003 U.S. Supreme Court ruling, which upheld an earlier Colorado Supreme Court decision in favor of San Luis residents.4

One of the basic themes underscoring the artistic creation of La Sierra concerns the cultural, social, and lineal attachment to place where memory (i.e., individual and collective) is configured as both the agent and the subject of recall while art, expressed as pictorial narrative, is the cultural form or its material manifestation. Throughout the long process of resistance to private ownership of the land, the descendants of the San Luis settlers—the original grantees—claimed a certain degree of “moral authority” not based on wealth or power but substantiated by their continuous cultural practice of respect and identification with the land through a stewardship predicated on ancestral rights and customary use. Ortega y Gasset suggests a similar, but more poetically expressed, affinity between identity and place: “Show me the landscape in which you live and I will tell you who you are” (quoted in Lane 1988:64).

People commonly inscribe their presence on the landscape in enduring ways, such as the apportionment of space and the construction of the built environment. Whenever Josephine Lobato documents evidence of the effects of this manifesting presence in her embroidered scenes of historical moments and cultural enactments, she metaphorically transforms “space” into “place.” In this way real environment becomes intelligible through visualization as an instance of place—a locus of happening—composed of actual and symbolic individual and group experiences.

Coupled with the cognitive is the kinetic. Memory is activated by stitching, and stitching is motivated by memory. I...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Figures

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Editors’ Introduction: Where Is the Color in the Colorado Borderlands?

- PART I Early Struggles

- PART II Pre-1960s Colorado

- PART III Contemporary Issues

- Contributors

- Index

- Footnote