- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Building a Resilient Twenty-First-Century Economy for Rural America

About this book

In Building a Resilient Twenty-First-Century Economy for Rural America, Don E. Albrecht visits rural communities that have traditionally been dependent on a variety of goods-producing industries, explores what has happened as employment in these industries has declined, and provides a path by which they can build a vibrant twenty-first-century economy. Albrecht describes how structural economic changes led rural voters to support Donald Trump in the 2016 election and why his policies will not relieve the economic problems of rural residents.

Trump's promises to restore rural industrial jobs simply cannot be fulfilled because his policies do not address the base cause for this job loss—technological change, the most significant factor being the machine replacement of human labor in the production process. Bringing a personal understanding of the effects on rural communities and residents, Albrecht focuses each chapter on a community that has traditionally been economically dependent on a single industry—manufacturing, coal mining, agriculture, logging, oil and gas production, and tourism—and the consequences of losing that industry. He also lays out a plan for rebuilding America's rural areas and creating an economically vibrant country with a more sustainable future.

The rural economy cannot return to the past as it was structured and instead must look to a new future. Building a Resilient Twenty-First-Century Economy for Rural America describes the source of economic concerns in rural America and offers real ways to address them. It will be vital to students, scholars, practitioners, community leaders, politicians, and policy makers concerned with rural community development.

Trump's promises to restore rural industrial jobs simply cannot be fulfilled because his policies do not address the base cause for this job loss—technological change, the most significant factor being the machine replacement of human labor in the production process. Bringing a personal understanding of the effects on rural communities and residents, Albrecht focuses each chapter on a community that has traditionally been economically dependent on a single industry—manufacturing, coal mining, agriculture, logging, oil and gas production, and tourism—and the consequences of losing that industry. He also lays out a plan for rebuilding America's rural areas and creating an economically vibrant country with a more sustainable future.

The rural economy cannot return to the past as it was structured and instead must look to a new future. Building a Resilient Twenty-First-Century Economy for Rural America describes the source of economic concerns in rural America and offers real ways to address them. It will be vital to students, scholars, practitioners, community leaders, politicians, and policy makers concerned with rural community development.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Building a Resilient Twenty-First-Century Economy for Rural America by Don E. Albrecht in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sciences sociales & Sociologie rurale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Manufacturing

Manufacturing is the process of turning raw materials into finished or semi-finished products. While manufacturing has always existed, during the Industrial Revolution the process became much more efficient, and the range of products expanded. The Industrial Revolution began in England in the late eighteenth century and was a result of the development of new energy sources and machines that allowed more and better products to be made in a shorter amount of time. An early catalyst for the Industrial Revolution was the development of the steam engine. The steam engine provided a source of energy to power a wide range of newly invented machines.

The first industry to be completely altered by the Industrial Revolution was textiles. Prior to the Industrial Revolution, the process of turning natural fibers such as wool, flax, or cotton into thread or yarn and then into cloth or clothing was a labor-intensive and tedious process and was mostly a home-based or cottage industry. Following the invention of the steam engine, increasingly efficient machines were developed that could do the necessary tasks mechanically. Soon, textile factories emerged with large hired labor forces that were vastly more efficient than home production. Additionally, the quality of the clothing produced by factories was typically much better than that from home production. Many rural residents moved to the city to find employment in the emerging factories.

After industrialization of the textile industry, other machines were developed that transformed virtually every other industry and nearly every aspect of human life. The industrialization of agriculture had especially great impacts, since prior to industrialization most people were involved in agriculture. Utilizing new machines, each individual farmer was much more productive and could manage a much larger operation; thus, fewer farmers were needed. As a consequence, many primarily rural and agricultural societies were transformed into urban and industrial societies. Another dramatic consequence of industrialization was the separation of work and family. Prior to industrialization, the family working together at their home did most of the economic production. In effect, the family was both a unit of production and a unit of consumption. After industrialization, the father would typically leave home to work and bring home a paycheck. The mother generally stayed home to care for the children. The family was no longer a unit of production, but rather simply a unit of consumption.

Millions of people were displaced from their jobs by these new industrial machines. Many skilled craftsmen such as cobblers, coopers, and blacksmiths were pushed out of business by industrial production of their products. Yet other jobs emerged to take their place. Most obvious were the new jobs in the manufacturing sector. In addition, with more people freed from the necessity of producing basic food or shelter, many people had opportunities to become skilled in medicine, art, literature, entertainment, and education. With greater levels of production, more people were able to afford these new opportunities. The result was that most people benefitted from these new opportunities, and the quality of life improved greatly for nearly everyone.

The new jobs emerging as a result of the Industrial Revolution required different knowledge and skills and often required people to live in different places. Urban communities generally benefitted, while rural communities struggled. Some people fought hard against the changes. For example, Luddites were a group of English workers who sought to destroy new textile machinery in an effort to prevent the changes they saw as threatening to their way of life. Opposition to change remains common in human communities.

The growing manufacturing sector needed more and more workers. From the outset, there was conflict between this increasingly large labor force and the owners of factories. The workers desired to be paid enough to allow a somewhat comfortable standard of living, to provide opportunities for their children, and to have a safe working environment and reasonable working hours. Ownership desired to keep costs as low as possible, while maximizing production. In many ways, these goals are in direct opposition. For management to provide what labor desired would reduce profits. As the industrial sector grew, relations between labor and management became among the most important concerns of industrial societies. When Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels wrote the Communist Manifesto in 1848, their primary purpose was to provide a political system that protected the rights of workers in industrial societies.

The methods and machines of the Industrial Revolution soon crossed the Atlantic from Britain to America. Most Americans embraced industrialization, and in time the United States became the most advanced industrialized country in the world. Throughout the nineteenth century, rapid developments occurred in industries such as steel and oil production. Railroads were built from one end of the country to the other, making it possible for the inputs and products of the growing industrial sector to get transported quickly and with greater cost effectiveness. Early manufacturing was concentrated in the northeastern quadrant of the country, largely because of access to a labor force and sources of energy.

In time a large textile-manufacturing sector emerged, primarily in the South. By the close of World War II, 1.3 million Americans were employed in textile and apparel manufacturing. At this time, about 40 percent of the North Carolina labor force was employed in the textile sector. Textile manufacturing in the South tended to pay lower wages than the heavy manufacturing occurring in northern and eastern states.

Labor disputes soon became prominent in the US industrial sector. In most early labor disputes, government officials and law enforcement tended to side with management and ownership. On a number of occasions in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, industries hired private security agencies, such as the Pinkerton Agency, a private detective service, to infiltrate unions and intimidate workers. In several cases, conflicts between labor and management resulted in injuries and death. In the Great Strike of 1877, more than 100 people were killed. The Homestead Strike of 1892 was a conflict between the steel workers and management at a Carnegie Steel Company plant in Homestead, near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Ownership brought in the Pinkertons, and battles between the workers and the Pinkertons resulted in the deaths of at least a dozen people. Numerous other labor conflicts occurred in a wide range of locations.

In the years immediately following World War II, the US manufacturing sector embarked on a period of spectacular growth. Utilizing continually improving technologies, American manufacturers were able to produce a wide range of products quite cheaply, and then market these products throughout the world. Innovation was aided by public investment in basic research at universities that resulted in new products, techniques, and ideas. Advanced industrialization resulted in high productivity, which led to high profits. Under these circumstances, unions were able to seek and obtain higher wages for their workers. This progress resulted in the historically unique situation in which ordinary workers were earning relatively high incomes (Bluestone and Harrison 1982; Chevan and Stokes 2000; Danziger and Gottschalk 1995; Sassen 1990).

With millions of well-paying jobs in manufacturing, the United States was very much a middle-class nation in the decades following World War II. Persons getting a manufacturing job could generally afford a home, a car, a family vacation, and, if they wished, send their children to college. Through these decades there was a steadily improving standard of living, with each generation doing measurably better economically than their parents. Between the end of World War II and 1973, real wages doubled for the average American worker. It was a time of optimism, with most people expecting economic growth to continue (Brick 1998; Uslaner 1998). In his much-acclaimed book The Affluent Society, the well-known economist John Kenneth Galbraith (1958) wrote that greater production would result in economic prosperity reaching nearly all Americans and that only “pockets” of poverty would remain.

While manufacturing occurred throughout the country, the Upper Midwest and Northeast became the most industrialized region of the country. Nearly all cities in this region had substantial manufacturing enterprises. Some cities became known for their primary product. For example, the auto industry was centered in Detroit, Pittsburgh was the steel city, and tires were manufactured in Akron, Ohio.

Initially, most US manufacturing occurred in urban areas. In time, some industrial firms began moving to rural areas in an attempt to pay lower wages to their workers. In rural areas, industry could employ farmworkers displaced by improving technology and seek to avoid unionization. The wages one could earn in manufacturing generally far exceeded what could be earned in farming, thus it was relatively easy to attract the necessary workforce. Soon manufacturing employment far exceeded farm employment, even in rural areas, and the proportional dependence of rural areas on manufacturing exceeded that of urban areas (Low 2017). Communities that could obtain an industrial firm often had the benefit of an employer that paid relatively high wages and employed workers that lacked an advanced education. During this era, community economic development often consisted of attempting to attract an industrial firm to operate there.

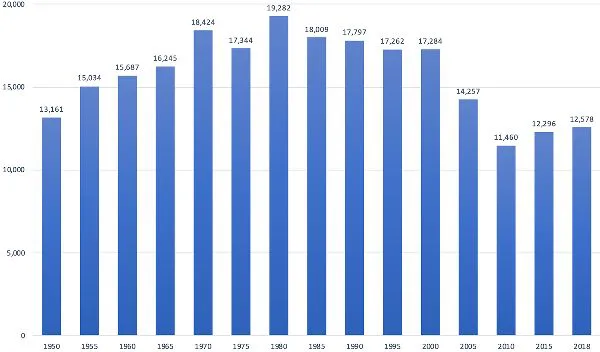

Employment in manufacturing continued to grow until reaching a peak in 1979, with more than 19.5 million employees (figure 1.1). Since that time, there has been a somewhat steady decline in manufacturing employment. Declines were especially pronounced from 2000 to about 2010. In 2018, the number employed in the manufacturing sector was down to about 12.6 million, a 55 percent decline from 1979. There has been a small rebound since 2010, as the economy recovers from the 2008 recession. As the number of jobs declined, there was not a corresponding decline in the number of people seeking these jobs. As a result, management was able to pay lower wages for unskilled workers and reduce the power of the unions (Kingsolver 1989; Rosenblum 1995). Consequently, the power of unions today is much reduced, and the proportion of workers belonging to a union is much lower compared to the decades immediately following World War II.

Figure 1.1. Manufacturing employment in the United States (in thousands), 1950–2018

While some industries moved to countries with lower wages and less-restrictive environmental regulations, the vast majority of jobs lost in manufacturing are a consequence of technological developments whereby machines replace human labor in the production process (Hicks and Devaraj 2015; Rasker 2017). Thus, even though employment numbers are down, the value of production from manufacturing continues to grow. In fact, the value of goods produced in manufacturing in the United States has doubled since the 1980s. With improved technology, a small number of workers can produce more than a much larger workforce in times past.

The greater reliance on technology also means that the modern manufacturing sector requires workers with more skills and higher levels of education. Between 2000 and 2014, the proportion of manufacturing employees with at least a bachelor’s degree increased from 22 percent to 29 percent. No question, this trend will continue and the capacity of manufacturing to provide jobs to unskilled workers will diminish. A more educated and skilled workforce also means that average wages in the manufacturing sector have increased and likely will continue to increase. In contrast, wages continue to fall for the declining number of unskilled workers.

It is also important to understand that manufacturing is not a monolithic industry and that some sectors of that industry have done better than others. The skills needed and wages paid also vary by manufacturing sector. For example, between 2002 and 2012, motor vehicle parts manufacturing lost 254,000 jobs, which was 53 percent of that industry’s labor force. During this same time period, household and institutional furniture manufacturing lost 185,900 jobs, which was 85 percent of their labor force. In the South between 1997 and 2009, 650 textile-manufacturing plants closed, with thousands of workers being laid off. The plants that remain are more automated, require a smaller but more skilled labor force, and are more productive than plants that existed in the past.

In rural areas, the most important manufacturing sector is food manufacturing. Wood manufacturing is also heavily concentrated in rural areas. For both of these sectors, there are advantages for manufacturing firms of being near the resource (agricultural products or trees). Employment in food manufacturing has remained relatively constant and without the drastic job losses experienced by other sectors. Wood manufacturing has not been so fortunate, as there has been substantial job loss. In rural areas, the largest employment declines have been in textile and apparel manufacturing.

Manufacturing’s Decline

The manufacturing proportion of US GDP has been declining as other sectors of the US economy continue to grow. In 1958, manufacturing’s share of the GDP reached a peak at 28 percent. Between 2001 and 2015, the proportional share of the GDP from manufacturing declined from 14 percent to 12 percent.

With the number of jobs declining and plants closing since about 1980, the Upper Midwest region became known as the “Rust Belt.” The implications of declining employment in manufacturing were dramatic, as many cities lost the most important sector of their economy. Of the many cities that could be used as an example of the consequences of deindustrialization, Youngstown, Ohio, and Flint, Michigan, are often considered the poster children.

Youngstown, Ohio

Around the turn of the twentieth century, Youngstown became one of the most important steel-producing cities in the country. By 1930, steel mills lined the Mahoning River for miles and the population of Mahoning County (where Youngstown is located) grew from 55,979 in 1890 to 236,142 in 1930 and then to 303,424 in 1970. With thousands of well-paying jobs in the steel industry, the city was prospering.

The decline of the steel industry in Youngstown began on September 19, 1977, a day remembered locally as “Black Monday.” On that day, 5,000 workers were laid off without warning when they arrived at work. The loss of jobs continued through the 1980s as more steel mills closed. Some plants began to mechanize in an attempt to remain profitable, which resulted in the loss of even more jobs. Overall, more than 50,000 jobs in the steel industry were lost in the county, and the steel industry has largely disappeared. The massive steel factories are now nothing more than rusting hulks. With thousands of jobs disappearing, large numbers of people moved away. Those who remained are living in a city plagued by crime, drugs, and deteriorating schools and infrastructure.

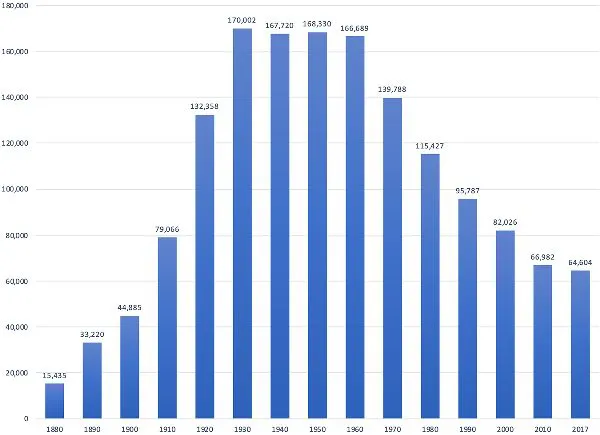

According to US Census data, between 2010 and 2016, Youngstown had the highest rate of population decline and the highest poverty rate among the 100 largest metropolitan areas in the country. By 2016, the population of Mahoning County was down to 230,008, a 32 percent decline from 1970. The city of Youngstown has done even worse than the rest of Mahoning County. In 1930, the city’s population was 170,002; in 2017 this number had been reduced to 64,604 (figure 1.2). Journalist Chris Hedges stated that Youngstown is “a deserted wreck plagued by crime and the attendant psychological and criminal problems that come when communities physically break down” (Hedges 2010).

Fi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. Manufacturing

- 2. Agriculture

- 3. The Coal Industry

- 4. Fracking, Horizontal Drilling, and Oil and Gas Production

- 5. Northwest Forests and the Logging Industry

- 6. Mineral Development

- 7. Amenity and Tourism Communities

- 8. Federal Environmental Policies and Rural Economic Development

- 9. Federal Land Management and Rural Economic Development

- 10. Building a Twenty-First-Century Economy for Rural America

- References

- Index