1

The Unexplored Yellowstone

Prior to 1869, the rugged wilderness surrounding the headwaters of the Yellowstone River, in the northwestern corner of the Wyoming Territory, had remained relatively unexplored, save for Native Americans, trappers, and prospectors who ventured into the area in search of game or gold. Mountain men spoke of extraordinary wonders such as spouting geysers, bubbling mud pots, towering waterfalls, and a spectacular mountain lake; but their stories seemed exaggerated and were dismissed as ramblings of those who had spent too much time alone in the wilderness. Even the accounts of Jim Bridger, the legendary scout, trapper, and hunter who served as a guide to US Army and civilian parties alike, were often dismissed as embellished campfire tales.1

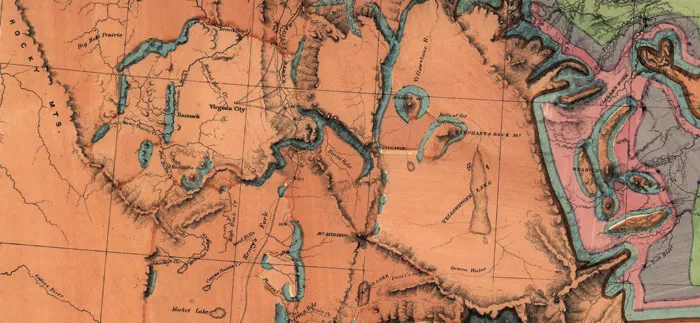

Stories about the mythical Yellowstone region began to spread among the growing population of the southern Montana Territory drawn to the area by the construction of the Northern Pacific Railroad, and some began hatching plans to venture into the region themselves. In September 1869, Charles W. Cook, David E. Folsom, and William Peterson, three men from Diamond City, Montana—just east of present-day Helena—made the first organized excursion into the heart of what is today Yellowstone National Park, intent on verifying the stories. Following the Yellowstone River and entering the region from the north, the trio visited rumored wonders such as Tower Fall, the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone and its waterfalls, Yellowstone Lake, and the Lower and Midway Geyser Basins on the Firehole River, where they witnessed the eruption of several geysers.

Despite being waylaid by an early season snowstorm during the first week of their trip, the party covered a remarkable distance in a short amount of time, probably due to the group’s small size. The trio exited the area via the Madison River at present-day West Yellowstone after less than a month in the region and returned to Diamond City.2

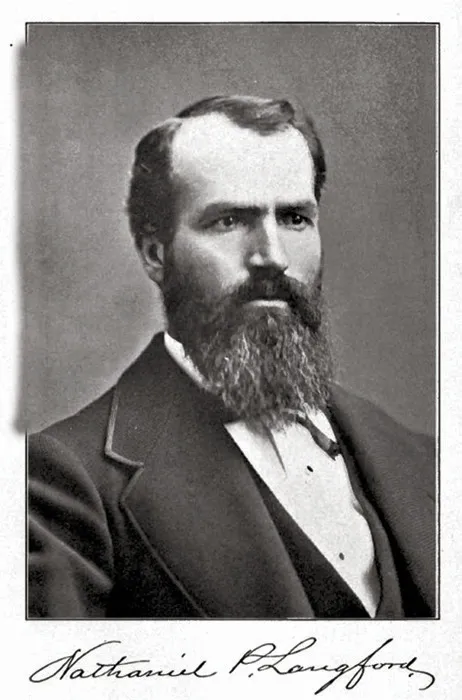

Though the Cook-Folsom-Peterson Expedition confirmed many of the stories about Yellowstone, major eastern publications were reluctant to publish their written accounts, dismissing descriptions by the relatively unknown explorers as unreliable.3 However, their stories gained regional interest and drew the attention of Henry Washburn, surveyor-general of the Montana Territory, and businessman Nathaniel P. Langford, former US collector of internal revenue for the Montana Territory. The pair soon began organizing a larger party to explore the region more extensively in the coming summer.

In mid-August 1870, Washburn and Langford’s party departed Helena for the Yellowstone region. Their group included thirteen civilian travelers, mostly fellow businessmen and political associates from the Montana Territory. Jay Cooke, a personal acquaintance of Langford and a major financial backer of the Northern Pacific Railroad, saw an opportunity to publicize Yellowstone as a destination for tourists who would travel to the region by rail. Cooke funded his friend’s endeavor and eagerly awaited Langford’s findings.

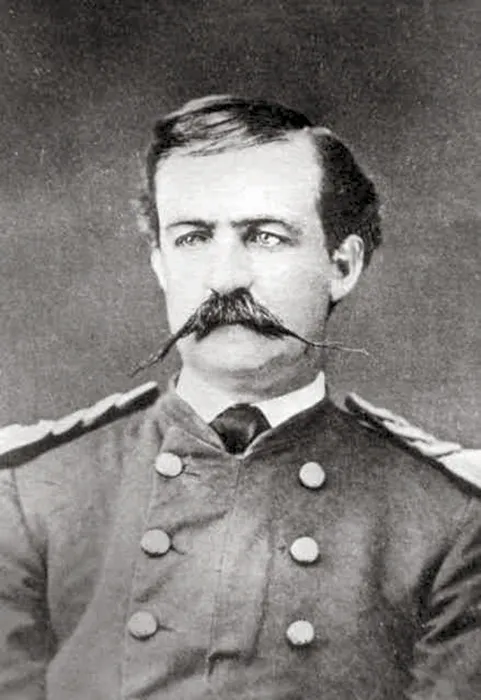

Given the influential status of many of the civilian members, Washburn lobbied for a military escort to accompany the explorers into potentially hostile Indian country. Led by Lt. Gustavus C. Doane, a small contingent of six troops from the US Army’s Second Cavalry in Fort Ellis, near Bozeman, was assigned to travel with the group.4

The party followed the same general route the Cook-Folsom-Peterson Expedition took the year before. At Tower Fall, the group turned away from the Yellowstone River and headed south, ascending what is today Mount Washburn near Dunraven Pass, and continued to the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone River. It was here that Walter Trumbull, a civilian member of the party, and Charles Moore, a US Army private in the military escort, would sketch the first crude representations of the Upper and Lower Falls of the Yellowstone.

Now reunited with the Yellowstone River, the expedition followed the waterway south to Yellowstone Lake. At the river’s outlet at the lake’s north end, they followed the eastern shoreline in a clockwise circumnavigation, climbing some of the high peaks of the Absaroka Range to the east and near the upper Yellowstone River to the south. At West Thumb, the party turned west, crossed the Continental Divide near present-day Craig Pass, and struck the Firehole River, following it north to the Upper Geyser Basin.5 Langford would later detail their witness to what is generally known to be the first named geyser in Yellowstone:

After exploring the basin and observing and naming several geysers, the party traveled north along the Firehole to its junction with the Madison River. Like the Cook-Folsom-Peterson group the previous year, they followed the Madison west out of the region. Near Virginia City, Montana, the party disbanded, Doane taking his small military contingent back to Fort Ellis while the rest of the party returned to Helena in late September.7

Local interest for a report from the highly publicized trip reached a fever pitch upon the party’s return to Helena. The editions of the Helena Daily Herald containing the expedition’s early reports sold out, prompting the newspaper to republish the articles only a few days later. Due to the reputable status of many of the influential members of the expedition—and the harrowing account of one member, Truman Everts, who became separated from the party and spent thirty-seven days alone and lost in the Yellowstone wilderness8—subsequent reports were widely published in several large newspapers and periodicals, including Scribner’s Monthly: An Illustrated Magazine for the People, Denver’s Rocky Mountain News, ...