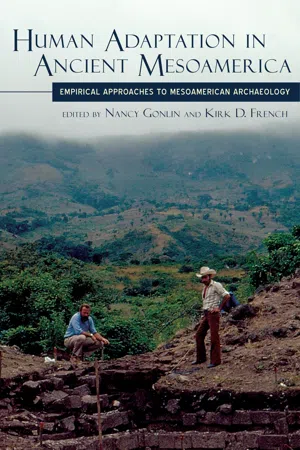

Human Adaptation in Ancient Mesoamerica

Empirical Approaches to Mesoamerican Archaeology

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Human Adaptation in Ancient Mesoamerica

Empirical Approaches to Mesoamerican Archaeology

About this book

This volume explores the dynamics of human adaptation to social, political, ideological, economic, and environmental factors in Mesoamerica and includes a wide array of topics, such as the hydrological engineering behind Teotihuacan's layout, the complexities of agriculture and sustainability in the Maya lowlands, and the nuanced history of abandonment among different lineages and households in Maya centers.

The authors aptly demonstrate how culture is the mechanism that allows people to adapt to a changing world, and they address how ecological factors, particularly land and water, intersect with nonmaterial and material manifestations of cultural complexity. Contributors further illustrate the continuing utility of the cultural ecological perspective in framing research on adaptations of ancient civilizations.

This book celebrates the work of Dr. David Webster, an influential Penn State archaeologist and anthropologist of the Maya region, and highlights human adaptation in Mesoamerica through the scientific lenses of anthropological archaeology and cultural ecology.

Contributors include Elliot M. Abrams, Christopher J. Duffy, Susan Toby Evans, Kirk D. French, AnnCorinne Freter, Nancy Gonlin, George R. Milner, Zachary Nelson, Deborah L. Nichols, David M. Reed, Don S. Rice, Prudence M. Rice, Rebecca Storey, Kirk Damon Straight, David Webster, Stephen L. Whittington, Randolph J. Widmer, John D. Wingard, and W. Scott Zeleznik.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Chapter 1

Empirical Archaeology and Human Adaptation in Mesoamerica

A Genealogical History of Approaches to Human Adaptation and Cultural Ecology

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Foreword

- Preface

- Section I: Introduction

- 1. Empirical Archaeology and Human Adaptation in Mesoamerica

- Section II: Water and Land

- 2. Water Temples and Civil Engineering at Teotihuacan, Mexico

- 3. Measuring the Impact of Land Cover Change at Palenque, Mexico

- 4. Complementarity and Synergy

- Section III: Population and Settlement Studies

- 5. Chronology, Construction, and the Abandonment Process

- 6. The Map Leads the Way

- Section IV: Reconstruction and Burial Analysis

- 7. The Excavation and Reconstruction of Group 8N-11, Copan, Honduras

- 8. The Maya in the Middle

- Section V: Political Economy

- 9. Life under the Classic Maya Turtle Dynasty of Piedras Negras, Guatemala

- 10. The Production, Exchange, and Consumption of Pottery Vessels during the Classic Period at Tikal, Petén, Guatemala

- Section VI: Reflections and Discussion

- 11. Forty Years in Petén, Guatemala

- 12. Two-Katun Archaeologist

- List of Contributors

- Index