![]()

Part I The Making of a News Grazer

![]()

Chapter 1 Why Don’t We Trust Congress and the Media?

This book investigates how changing news-gathering habits are affecting our public perceptions of politicians and the media broadly. Particularly, I argue that the sources and devices we use to access news have grown dramatically with the advent of new communications technologies, and these changes are affecting public perceptions of politics. The ultimate goal of this book is to understand better how public perceptions of Congress and the media are formed and to explain how these perceptions are shaped by our own media choices.

Politicians and journalists have never been trusted professional classes comparatively. Gallup Polls have tracked the public’s trust of different professions over time. According to Gallup, members of Congress, as a professional class, are less trusted than car salespeople and telemarketers (Gallup 2016). Journalists, meanwhile, have declined in public standing. The percentage of Americans rating journalists as having “low” or “very low” honesty and ethical standards has doubled since the early 1990s. Hetherington and Rudolph (2015) argue how the contemporary decline in political trust is reaching unprecedented levels and contributing to a polarized Congress.

Of course, the American political system is largely based on public distrust of political elites. It is grounded in principles of popular sovereignty, checks and balances, separation of powers, and limited government. This constitutional design was partly an outgrowth of public distrust toward centralized authority. While it is part of our American political ethos to distrust centralized power, we also tend to distrust congressional compromise, denouncing it as unprincipled and political (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse 1995). Instead, most Americans prefer elected politicians who remain consistent with their base constituencies and core values.

For these reasons, Congress has remained unpopular over time, sometimes referenced as the “broken branch” of our federal government (Fenno 1975). Congress has generally been held in lower public esteem over time compared to the executive branch and Supreme Court. It is precisely because of its public transparency and conflicting voices compared with the other branches that Congress is disliked. Congress is on public display, exposing Americans to the wheeling and dealing, appeals to special interests, and partisan rhetoric of representative government. This public transparency is mediated through a television, computer, and smartphone screen increasingly, and this mediated communication is another thing this book is about.

Hibbing and Theiss-Morse (1995) find that Americans do not like partisan conflict, long debate, and crass bargaining, instead wishing for a quieter, more agreeable Congress. Of course, this public preference for a populist consensus—a democratic wish that we will all agree with a well-defined national interest—does not occur in practice (Marone 1998). It is at odds with a legislative process that reflects our national diversity. Most Americans prefer politicians who remain consistent with their base constituencies and core values. In practice, though, effective legislatures compel broad-minded leadership, dialogue, and conciliation among diverse interests to bring about collective action. Americans do not trust or like Congress in practice.

Acknowledging this long tradition of congressional disapproval, I argue that the level of public acrimony toward Congress has deepened in the past decade. According to Gallup Polls, public approval of Congress in 2001 stood at a high of 84 percent. This brief, transcendent point of congressional approval reflected a rally-around-the-flag effect after 9/11. Public approval of all government institutions—Congress, the presidency, Supreme Court, and the military—peaked after the 9/11 terror attacks. Since 2001, though, public approval of Congress has steadily declined more sharply than for other institutions. In fact, congressional public approval dipped to about 10 percent approval or even single digits in 2013 after Congress’s government shutdown battle. By 2017, Gallup Polls measured that public approval of Congress increased after the 2016 presidential election to 28 percent and then regressed back to now routine low numbers for both Republicans and Democrats. Despite some variability and regardless of your partisan views, we do not like Congress.

Likewise, we increasingly distrust the media. Americans’ trust in the news media was at its highest in the mid-1970s in the wake of investigative journalism regarding Watergate scandal and Vietnam. Americans’ trust leveled to the low to mid-50s throughout the 1990s and early 2000s. However, since then, Americans’ trust in the media has fallen slowly and steadily. By 2016, less than a third of Americans stated that they had “great deal” or “fair amount” of trust in mass media to “to report the news fully, accurately and fairly” (Gallup 2016).

There are many explanations for why we do not trust politicians and the media. Trust in government, generally, has declined from highs in the 1950s and 1960s, and congressional distrust is just part of this larger issue. My interest, though, is to point out a connection between media and congressional distrust. I argue that our practices and attitudes toward news media are driving the more recent depths and intensity of congressional distrust over the past two decades. By proposing and investigating a new media explanation for congressional distrust, I do not imply that other explanations should be discounted. For instance, I am not arguing that excessive partisanship, crass pork barreling, special-interests lobbying, incumbency advantages, or political scandal are not all possible sources of congressional disapproval. I am only suggesting that an explanation grounded in the role of media is less recognized and understood.

My thesis is that our changing news-gathering habits are contributing to recent public distrust of Congress. The media outlets in which we view, read, or hear about Congress have expanded as new media technologies have supplanted traditional news media. Additionally, the diffusion of media devices, like smartphones, DVRs, and tablets, has resulted in an increasingly fragmented and distracted news audience. Media choice is not only altering who accesses news and how they do it; more important, I argue that it is also changing the news itself. I posit a news-grazing explanation of how the public views Congress that I describe subsequently.

News Grazing

Today’s media consumers are flooded by choice. We click a remote control, tap a computer keyboard, or touch a tablet screen. But consider for a moment a world without these media screening devices. Would we watch the same programs and access the same information without them? When watching television, would we still be apt to turn from channel to channel if we had to get out of our seats and stand in front of the TV while doing it? Maybe not. If people were less apt to click from channel to channel, would so many channels exist today? Maybe not. Beginning with the remote control, media-screening technology has facilitated media choice. The remote control facilitated greater levels of television watching and highly influenced the manner in which we watched TV. We can be more selective, making a split-second judgment in our viewing. If a program does not tickle our immediate fancy, it takes little to no effort to merely click to another channel … and another … and another.

The remote control, though, was merely one of the first communication technologies that allowed us to screen or manage media messages. (I would emphasize that the remote control is old technology.) Consider the explosive growth of communication technologies that increasingly allow us to be both more selective with information but also distract us from the moment. Just like the remote control, more recent media technologies—smartphones, tablets, DVRs, video games, and social networks—offer further media choices and distractions. News media now extends far beyond the bounds of its traditional sources.

Not surprisingly, this media gadgetry and choice consumes more of our time and often decreases our focus on other tasks. For some heavy media users, use of media technologies may even approach many disquieting characteristics of a psychological addiction: spending large amounts of time, using it more than one intends, thinking about and repeatedly failing to reduce use, giving up other social activities to use it, and reporting noticeable withdrawal symptoms when stopping the activity. Psychologists dispute whether media addiction is a valid clinical disorder; still, for some, media use can be a compulsive behavior (Widyanto and Griffiths 2006; Winkler et al. 2013). Perhaps you may check your e-mail, Facebook, or text messages more times during the day than you care to admit.

Even if it is not a compulsive behavior, however, media use can become a disruption to other activities. In many ways, media choice and surfing break our attention. Individuals’ media practices are increasingly bumping into social norms of appropriateness—cell phones going off in class or church, texting while driving, or TV watching or web-surfing during meals. Media technology—and, correspondingly, media choice—has become pervasive in our work and lifestyle.

This book is about the effects of media choice on politics. Our focus is not on the media technologies themselves but rather on our behavioral responses to them. Particularly, how have our news-gathering habits changed in response to media choice and technologies? Additionally, have these changed habits led to different formats of news media coverage, and correspondingly, are these different news formats changing public attitudes toward politics? I track how citizens adapt to media choice by changing their habits for collecting news. I refer to these still emerging habits as news grazing—the decline in traditional routinized news-gathering habits and a corresponding reliance on alternative news sources and formats.

I am particularly interested in a set of public attitudes toward politics—our perceptions of Congress and the news media. Why Congress? The U.S. Congress exists as our political system’s clearest laboratory of democracy, a bicameral legislature that reflects our vices and virtues as a culture. Congress has never been popular in terms of public opinion, but it remains a resilient and hopeful institution for our popular governance. Showing how our media consumption habits affect our perceptions of politicians and institutions could sensitize us to our own media choices. Perhaps it may lead some to be more thoughtful media consumers.

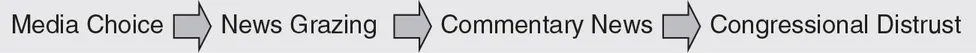

Our thesis in this research is that growing media choice is indirectly and unintentionally altering Americans’ political perceptions of Congress. I argue media choice is altering how we collect news, resulting in an emerging class of news grazers. In response to news-grazing habits, news producers and makers have correspondingly altered the news itself. I argue that a rising proportion of what we call commentary news formats is affecting how we perceive our politicians and political system. I argue that Americans consume greater amounts of news commentary than in the past. Particularly, I assess whether this commentary news affects perceptions of conflict and polarization between parties and within Congress. Figure 1.1 reflects my news-grazing theory of how media contributes to distrust toward democratic institutions.

Figure 1.1 A News-Grazing Theory of Media and Congressional Distrust

Source: Created by the author.

The goal of this analysis is to show how our simple, everyday decisions about how we collect news may have collective consequences for our politics, in ways that we perhaps do not fully recognize. By changing how we watch our news, we may be altering the news itself and, correspondingly, how we perceive our political world. Our growing perceptions of congressional conflict and polarization may partly be manifestations of the growing fragmentation of media audiences and our growing distractedness from any single media source. I do not argue that today’s polarized parties and Congress are wholly or even mostly due to a fragmented media, only that news grazing and commentary news are contributing to congressional distrust.

Our specific focus is on how Americans collect political news—news stories relating to government officials, government institutions, elections, and public policy conflicts. Political news is an essential means for citizens to frame and evaluate issues of government performance. Whether we watch television news, read a daily newspaper, or scan online stories, our political news gathering helps us to understand and participate in a democratic process. This news gathering leads us to think, update our beliefs, discuss politics with others, and participate in elections.

In later chapters, I argue that the growth of news media sources has affected the range and style of coverage. Particularly, I show that television political news is increasingly delivered in commentary formats and less in traditional news formats. These commentary news formats imbue the news with opinion, urgency, conflict, or satire. These engaging forms of commentary news elevate our interest and possibly keep us from clicking away. I evaluate whether these commentary formats affect our public attitudes toward Congress, legislators, and party leaders.

The organization of the book follows the stages of our argument. In Part I, I investigate whether and how changing news-gathering habits have affected news formats and production. After this introductory chapter, Chapter 2 investigates how Americans’ news-gathering habits have evolved with media choice, investigating the first causal relationship posited in Figure 1.1. Chapter 3 explores the media and political elite response to these changing habits, analyzing the second causal relationship in Figure 1.1. I conclude from Part I that media choice has created an increasingly distracted and fragmented viewership in which news makers and producers must work harder to engage.

Part II of the book analyzes the attitudinal effects of commentary news formats, the final causal arrow in Figure 1.1. Chapter 4 evaluates whether programs that include a clear mix of opinion along with the news affect how we perceive Congress and its members. Chapter 5 explores the effects of news urgency—breaking news and debate formats in which the volume and tone of news delivery attract our attention. Finally, Chapter 6 investigates how perceptions may be altered by satirical news—formats that blend humor and news. The concluding Chapter 7 returns to our broad questions of low congressional trust and citizen perceptions, whether contemporary media merely reflects or rather conflates the congressional divide.

The rest of this chapter elaborates further on my news-grazing concept, as well as different theories of congressional disapproval. I first review the growth of media choice and news media formats. I then review different accounts of congressional disapproval, proposing a news-grazing explanation in which contemporary media promote perceptions of partisan distrust and institutional conflict. An engaging and sometimes divisive media may not be the primary means of congressional disapproval; still, media may contort rather than clarify public perceptions of Congress.

The Evolution of Media Choice and Screening

In 1950, Zenith developed an electronic device called “Lazy Bones.” This product was an accessory to the television, which was rapidly gaining popularity as an everyday communications medium. Lazy Bones was a motor that attached to the television’s tuner. When activated, the motor would rotate the tuner, or “knob,” and allow watchers to view another station. The motor was attached to a remote electronic controller by a cable. Thus, by pressing the button on the attached controller, a television watcher could change channels from across a room without having to get out of her seat.

As a product, Lazy Bones was a failure. There were only a few stations to choose from in the early 1950s, and given the limited programming, viewers only turned on the television when there was a specific program they wished to view. When the program was through, the television was turned off. In that environment, a product that allowed people to turn channels without getting up and walking over to the television did not offer much added benefit. Also, the long cable that stretched across the floor from the television to the controller was an eyesore and considered more of a domestic trip wire than a technological advancement.

Despite these humble beginnings, the idea of this electronic TV knob was revolutionary. Lazy Bones was the world’s first commercial television remote control. And when Robert Adler invented the ultrasonic wireless TV remote control in 1956, the device was on its way to becoming more than jus...