![]()

1

LEADERS AND LEADERSHIP TYPES

LEADERSHIP HAS BEEN a feature of humanity since its early beginnings. Hundreds of thousands of years ago, our ancestors hunted big animals for survival. When hunters faced prey that could overpower them, coordination was needed, and coordination required leadership. Leadership became ever more important as the complexity of human societies increased: from small bands of hunter-gatherers (twenty to fifty people) to villages (several hundreds of people) to cities (several thousands of people) to kingdoms encompassing many cities (several hundreds of thousands of people) to empires (millions of people).1 And, as human complexity increased, the number of leaders, and the complexity of the demands placed upon them, increased.

Today’s complex society would come to a standstill without leadership. It is not an exaggeration to state that leadership is one of the key issues of our times. Countless people occupy leadership positions, whether in government, companies, churches, nongovernmental organizations, schools, nonprofit organizations, or elsewhere. Leadership courses and programs are among the most popular offerings in the executive development programs of many business schools. For example, at UNC’s Kenan-Flagler Business School, programs for which the majority of content is about leadership account for two-thirds of the total revenue of Executive Development. When I did a Google search on “leadership,” I got over five billion hits! Clearly, leadership is on the minds of many people.

WHAT IS LEADERSHIP?

Leadership is the ability of an individual to influence others to achieve a common goal.2 This definition contains five components. First, leadership is relational. It exists only in relation to followers. Without followers, there is no leader. Second, leadership involves influence. Without influence, leadership does not exist. But where does influence come from? The most obvious source is positional authority. The CEO of a corporation has more influence than an assembly-line worker. Yet, you can also influence followers over whom you have no authority by methods such as rational persuasion, inspirational appeal, consultation, ingratiation, personal appeal, forming a coalition, or relentless pressure.3

Third, leadership is a process. Leadership usually does not happen in just one particular instance, but often involves a complex system of moves/ actions to accomplish a goal over a period of time. Fourth, leadership includes attention to common goals. By common, I mean that leader and followers have a mutual purpose. Leaders direct their energies toward others to achieve something together. This requires awareness of the current state, some vision of a desired future, and an ability to move from where you are to where you want to be.

Finally, leadership is about coping with change. The common goals are often different from what the organization has done hitherto. Part of the reason why leadership is so important is that the (business) world has become more competitive and volatile. Major changes occur ever more often and are more and more necessary to survive and compete effectively in this new environment. As leadership thinker John Kotter puts it, “More change always demands more leadership.”4

LEADERSHIP TRAITS

Leadership scholars have long debated what makes great leaders. Do great leaders need to have particular traits? Academic research has identified a long list, which includes the following core qualities:

• Intelligence: a person’s ability to learn information, to apply it to life tasks, and solve complex problems.

• Self-confidence: the ability to be certain about one’s own competencies and skills. It includes a sense of self-esteem and self-assurance and the belief that one can make a difference.

• Integrity: the quality of honesty and trustworthiness. Leaders that have integrity are believable and worthy of our trust.

• Sociability: the inclination to seek out and develop relational networks. Leaders who show sociability are friendly, courteous, tactful, and diplomatic.

• Emotional intelligence: the ability to identify, control, and express one’s own emotions, as well as the ability to handle relationships with others judiciously and empathetically.

• Humility: the quality of not thinking you are better than other people. It does not imply low self-esteem but rather a keen sense of one’s own cognitive or emotional limitations.

• Grit: the courage and determination that make it possible to continue doing something difficult or unpleasant.5

Are all these traits necessary? Interestingly, as you shall see in this book, the leaders differed greatly on these traits—some were highly sociable, others not; some showed exemplary integrity, others not at all; and so on. However, all these leaders had one thing in common: They all displayed grit. Setbacks did not cause the leaders in this book to give up; rather, they redoubled their efforts. They persevered in the face of opposition and disappointments. Or, as per the title of R&B singer Billy Ocean’s biggest hit, “When the Going Gets Tough, the Tough Get Going.”6

Grit is the common denominator that ties together the lives of all the leaders in this book. They all crossed the river, so to speak. Grit is required to be a great leader. Appendix A of this book contains the Grit Scale, a self-assessment tool you can use to determine how gritty you are. You can take the test now or wait until you have reached chapter 18, where I will discuss the scale and will tie your score back to specific parts in the book.

THE HEDGEHOG AND THE FOX

In the book The Hedgehog and the Fox, published in 1953, the Russian- British philosopher Isaiah Berlin quoted the seventh-century B.C. Greek poet Archilochus: “The fox knows many smaller things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.”7 According to Berlin, the distinction between hedgehogs and foxes marks “one of the deepest differences, which divide . . . human beings,” whether they are poets, scientists, managers, or politicians.8 This distinction is highly useful for the study of leadership.

HEDGEHOGS

Hedgehogs are people who relate everything to a single central vision, which serves as their universal organizing principle. This vision shapes how they think and feel, how they understand the world. Hedgehogs are risk takers who agree with the Persian king Xerxes (who we shall encounter in chapter 5) that “big things are won by big dangers.”9 Hedgehogs focus on end goals, gains, and outcomes, have a long-term view, and have a mindset of reshaping (organizational or environmental) constraints. They tend to brush aside criticism and command the attention of their audience with their captivating vision. People are moved by big ideas, by a vision of a different (better) future. Hedgehogs think in certainties: “If I do X, I will get Y.” Hedgehogs offer simple (not necessarily simplistic) solutions to complex problems. There is a reason why most gurus are hedgehogs: By reducing complexities to a few general rules, they offer a clear path forward to other, more uncertain minds.

In stark terms, hedgehogs know much better where they are going (ends) than how to get there (means). They are strategic visionaries rather than astute operators. This leads to the key potential weakness of hedgehogs: the failure to establish a proper relation between ends and means. In other words, their end goals can easily exceed the means at their disposal. According to historian John Lewis Gaddis, their trap is: “If you fail to prepare for all that might happen, you’ll ensure that some of it will.”10

King George III is an example of a particularly stubborn hedgehog. His overriding vision was royal sovereignty, which led to behaviors that pushed his American subjects away, while he did not have the means to suppress the revolt. Adolf Hitler was also a hedgehog. His evil overarching goal of world domination under the “superior” Aryan race and the concomitant destruction of Jewry were there for everyone to see. However, he failed to align means with ends—Germany was simply not strong enough to take on the Soviet Union, the British Empire, and the United States simultaneously.11 President Ronald Reagan was a successful hedgehog. Not a man of details, he had three overarching goals: smaller government, lower taxes, and strengthen the nation’s military. He achieved two out of three, which is an impressive result. Notwithstanding these successes, Reagan struggled with aligning goals and means. Lowering taxes and spending more on the military led to a significant increase in the budget deficit. This had to be rectified by his successor, George H. W. Bush, who lost the subsequent election in 1992 because of his broken promise not to raise taxes.

FOXES

Foxes pursue many ends, often unrelated and sometimes even contradictory, related to no clearly defined overarching goal. They might not even have a clear end goal at all. Foxes know much better how to get to somewhere (means) than where they are going (ends). They are operational rather than strategic leaders. They distrust grand schemes and simple explanations. They are prudent, cautious, detail-oriented, seeing everywhere obstacles and complexities. They have a relatively short-term view and focus on process rather than outcome. They have a good understanding of the means, but less of the ends. They tend to adapt to (organizational or environmental) constraints. Foxes think in eventualities: “If I do X, I might get Y, or possibly Z.” While foxes are keenly aware of the complex array of constraints they potentially face, this awareness can easily lead to paralysis. In Gaddis’s words, “If you try to anticipate everything, you’ll accomplish nothing.”12 Foxes struggle with articulating a clear priority among the many ends they want to achieve, which may leave their followers in confusion as to what the marching orders are.

President Bill Clinton is an example of a fox. He was one of the best political operators of the twentieth century, being able to switch course after he lost the midterm elections of 1994 and work with the Republican Congress. However, unlike Reagan, he was not driven by an overarching vision that captivated the nation. Another example is German chancellor Angela Merkel, who has been widely admired for her coolheaded leadership in the EU. Rather than entertain grand ideas of a “historic mission” or “strategic vision,” she aimed to solve today’s problems. Yet she has also been criticized as being too cautious and as squandering an opportunity to prepare Germany’s economy for the future.13

A third example is British prime minister David Cameron. He was an effective, but also opportunistic, politician who led the Conservative Party in 2010 back to power after having been in the opposition for thirteen years. However, he made the mistake of using a referendum on Brexit as a means to fight off the rise of the U.K. Independence Party (UKIP) and to quell dissension in his own party. He lost, resigned, and the United Kingdom entered years of political turmoil.

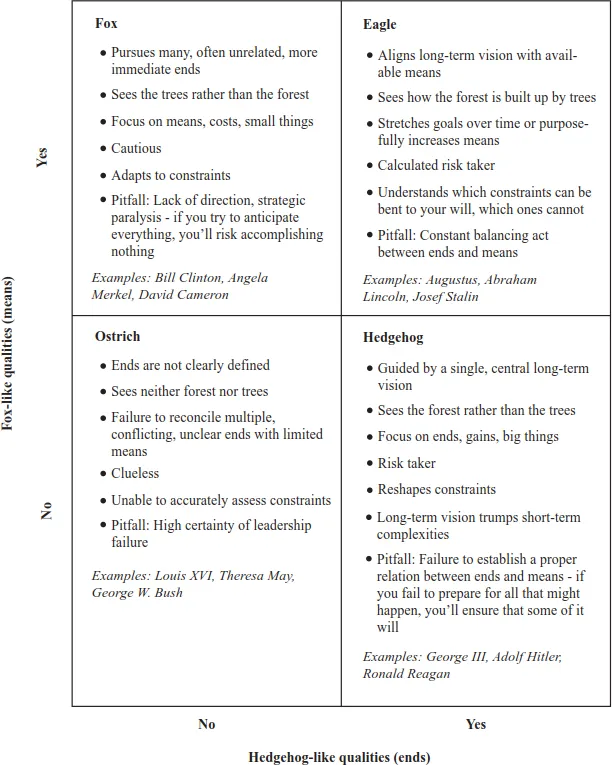

Initially, Berlin sharply contrasted hedgehogs versus foxes—you had to be one or the other. His distinction was used by political scientist Philip Tetlock, who found that foxes were consistently better predictors of future political events than hedgehogs.14 However, shortly before his death, Berlin acknowledged that some people are foxes as well as hedgehogs and some people are neither.15 Thus, we have four Aesopian possibilities, depicted in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Hedgehog-like vs. Fox-like Qualities

Note: Examples in the same cell do not imply moral equivalence.

EAGLES

I call leaders who combine the qualities of the hedgehog and fox, eagles. Eagles can see far in the distance—that is, have a farsighted vision— which they combine with great tactical agility. They excel in aligning potentially unlimited ambitions with necessarily limited capabilities. Eagles know where they are going (ends) and how to get there (means). They can deal with immediate priorities yet never lose sight of long-term goals. They may seek to increase their means before embarking on their journey. Alternatively, they stretch their goals over time, attempting to reach certain goals in the short term, put off others until later, and regard still others as unattainable.16

One example of an eagle is the Roman emperor Augustus. His overriding vision was to create a new political structure for the Roman Empire that would provide stability after a century of civil war. As we know, he succeeded beyond expectation in that goal. One n...