1

THE CYCLE

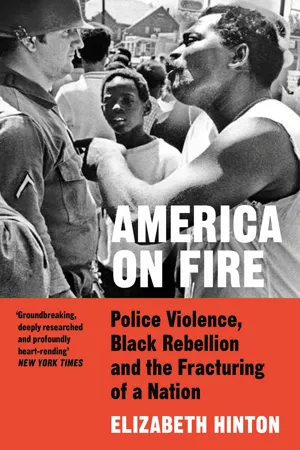

On the afternoon of July 7, 1970, during the third day of rebellion in Asbury Park, New Jersey, young people throw rocks at police as officers move in to break up the crowd. (Bettmann Archive / Getty Images)

THE RESIDENTS OF Carver Ranches didn’t have sidewalks, fire hydrants, or a sewer system. They did, however, have police patrolling their streets. Black Americans from Miami and Black migrants from the Bahamas first founded the three-hundred-acre community in Broward County, Florida, in the late 1940s, naming it after the celebrated scientist George Washington Carver. Teenaged children of Carver Ranches’ first generation were hanging out around midnight on a Saturday in August 1969, when a Broward County sheriff’s deputy drove by. One of the kids threw a rock at the police car. The small act of defiance provoked an outsized, and violent, reaction. The deputy stopped, stepped out, rushed the rock thrower, grabbed him by the shirt, and threw him in the back seat of his cruiser. The boy’s friends were not about to let him get taken away by the county cops for such an arbitrary offense. They opened the back-seat door and pulled him out, and the deputy hauled him back in. After several rounds of this, the children prevailed, and the rock thrower escaped into the growing crowd of people watching the encounter. Outnumbered, the deputy called for help. When reinforcements from three nearby police departments arrived, someone fired five shots at the officers. No one was hit. The sheriff later called the event a “near riot.”[1]

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, rebellions usually started when law enforcement meddled, often violently, in ordinary, everyday activity (a group of kids doing what kids do). They happened when police seemed to be there for no reason, or when the police intervened in matters that could be resolved internally (disputes among friends and family). Rebellions began when the police enforced laws that would almost never be applied in white neighborhoods (laws against gathering in groups of a certain size or acting like a “suspicious person”). Likewise, they erupted when police failed to extend to residents the common courtesies afforded to whites (allowing white teenagers to drink in a park but arresting Mexican American teens for the same behavior). “If they would just leave us alone there would be no trouble,” said a Black teenage boy who threw rocks in Decatur, Illinois, during an uprising in August 1969. His solution was a straightforward reaction to an obvious issue. Rebellion was always possible when ordinary life was policed, and often the mere sight of the police—who could potentially arrest, beat, or even kill you—was enough to prompt a violent response. Multiple occasions of seemingly arbitrary or unnecessarily aggressive police interventions accumulated into frustration and set off preemptive, violent reactions.

This was “the cycle”: the recurring pattern of over-policing and rebellion, of police violence and community violence, that helped define urban life in segregated, low-income, Black, Mexican American, and Puerto Rican communities in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The cycle occurred in cities across the nation, many of them smaller municipalities that are left out of standard accounts of this era. But it was precisely in these secondary cities that the War on Crime unfolded in the most lasting and influential ways, helping entrench racial inequality and put this nation on the path to mass incarceration. While every rebellion had its particular actors and causes, what is remarkable is the broad similarity between them.

THE EXCEPTIONAL MOMENTS of collective violence that occurred between the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 and the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968 were similarly ignited by police arresting Black people. The Harlem rebellion of 1964 was the outlier, a six-night revolt that began after a New York police officer killed a Black, fifteen-year-old boy. Coming two weeks after the enactment of the landmark Civil Rights Act, Harlem was the beginning of the “long hot summers” of Lyndon Johnson’s presidency. Watts in 1965 and Newark in 1967, though, each began in reaction to the arrest of a Black motorist. A police raid on a speakeasy in Detroit that year culminated in violence that Johnson called “the worst in our history.” More than one hundred other cities erupted in the spring of 1968 after the murder of King on April 4. The collective sorrow, anger, and disillusionment that followed King’s death was a turning point for the mainstream civil rights movement and its emphasis on nonviolence, a strategy that had failed to protect its most visible proponent from the violent forces of racism, and seemed, to many, incapable of securing true freedom for Black Americans. As Black Panther leader Eldridge Cleaver reflected in his article “Requiem for Nonviolence,” shortly after the assassination, King’s murder was “a final repudiation by white America of any hope of reconciliation, of any hope of change by peaceful and nonviolent means.” For Cleaver the only way for Black Americans “to get the things that they have a right to and deserve—is to meet fire with fire.” [2]

The King rebellions were also a turning point for policing. The day after King died, Johnson mobilized federal troops in the nation’s capital and in Chicago, Baltimore, and Kansas City, Missouri, soon after. “I don’t know how we handle these things,” Johnson admitted in a phone conversation with Chicago’s Mayor Richard Daley, roughly two weeks after the King-related unrest began. “But I know one thing: we’ve got to handle them with muscle and with toughness.” Johnson believed that the aggressive use of federal troops, more than twenty thousand soldiers in all, was responsible for leaving the country “in reasonably good shape” in the aftermath of the largest wave of domestic violence since the Civil War.[3] Not until the Los Angeles uprising in 1992 would the president summon federal troops to suppress Black rebellions. The lull was not a consequence of concern for the civil rights of American citizens, but a result of the professionalization of the police, a process that began under Johnson, whose administration instituted training programs for riot control and equipped local police forces with military-grade weapons.

The policing of the ordinary had sparked rebellions earlier in the decade: the dispersing of a crowd in Omaha in July 1966; the arrest of a Black bootlegger in a park in Kansas City, Missouri, in 1967; and the breaking up of fights between Black teenagers in Minneapolis and Sacramento that same year. But after King’s murder, police became the foot soldiers in a larger mission—the “War on Crime”—and there were more resources and more men than ever to carry it out. The federal allocation for local police forces went from nothing in 1964 to $10 million in 1965, $20.6 million in 1966, $63 million in 1968, $100 million in 1969, and $300 million in 1970—a 2,900 percent increase in five years.[4] As Johnson’s Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968 fueled the manufacture and national distribution of a riot-control arsenal, the governments and police forces of smaller cities—those outside of the initial beneficiaries, major metropolitan centers with large Black populations including Washington, DC, Detroit, and Los Angeles—were emboldened. The capstone of Johnson’s Great Society, the Safe Streets Act broke with the previous two hundred years of American history, establishing a direct role for the federal government in law enforcement and criminal justice at the state and local levels. It was the expansion of policing in response to the violent eruptions of the 1960s that set in motion the cycle that followed in smaller cities like Carver Ranches and Decatur.

President Johnson’s new national strategy was premised on preventing rebellion before it occurred and on identifying and arresting potential rioters or criminals. “More police patrols can be an effective, visible deterrent to crime,” federal law enforcement officials assumed. “More police patrols also lead to more and speedier arrests, which takes offenders out of action and lessens the chances of escape, thus serving as a deterrent.”[5] Increasingly, preventing rebellion “with muscle and with toughness” became the dominant strategy for fighting disorder, although it consistently failed to lead to the desired goal.

The national strategy set the tone, even in places that did not receive federal funds. Policing became more aggressive and intrusive in Black communities everywhere. Police often claimed to be responding to a tip, which the newspapers later reported to justify the officers’ actions and their presence in the community in the first place. The rock thrower in Decatur had a different take: “Police, they come out here looking for trouble,” he said.[6] What mattered was police were suddenly there. They were more likely to cause harm than offer protection, in the judgment of the rock thrower and his friends and counterparts in other American cities. The people being policed frequently refused to follow police orders and fought back, throwing rocks and jumping on officers’ backs to prevent arrests from being carried out.

It was a losing battle for a lone policeman or a small unit, and officers were forced to retreat to wait for reinforcements. This came in the form of cops in riot gear, as well as officers from neighboring cities, state troopers, or National Guardsmen who could be called by state governors depending on the size of the home department and the scale of the rebellion. When law enforcement left the area (if only temporarily), some residents did the same, while others turned on local businesses and other buildings, breaking windows and taking food, clothes, tires, and stereos from stores in what some police chiefs described as “hit and runs.” The participants in these outbursts outnumbered and often outsmarted the police, and they slipped away frequently, back into their homes or down familiar alleyways, over fences and dumpsters. The police sent in more police. The rebellion expanded. The escalation would often continue for another day or two before the rebellion burned out on its own or enough participants were arrested to have the same effect.

The proximate cause of the unrest did not present itself easily to many officials. “No explanation” could be found for the shooting at cops that began in Carver Ranches weeks after the initial rock-throwing incident in Florida. “We don’t know why it started,” said the Mayor of Fort Wayne, Indiana, after a rebellion. The Columbus Police Department in Ohio was “unsure” about what had led to the city’s revolt. The mayor of Jersey City spoke of “senseless, random acts of violence with no purpose or meaning.” Authorities in York, Pennsylvania, gave no reason for a four-night rebellion other than: “they don’t have anything else to do.”[7] The officials saw the violence as having no cause or meaning. In the rebellions of the immediate post-King era, Black and Brown participants saw themselves as being policed for nothing. They rebelled when the police appeared out of nowhere, and for no apparent reason.

RESIDENTS WHO WERE reportedly fighting one another frequently put aside their differences to battle a common adversary: the police who interrupted them. In Fort Wayne in August 1968, just before the school year began, a dozen Black teenagers started a rebellion at the McCulloch Recreation Center, where kids in the segregated Southeast side of the city often gathered. At around eleven o’clock, a Parks Department officer intruded on their evening (“a fight was reported”) and asked the group to disperse. The youths ignored him. They bent down and picked up stones and debris from the Center’s lawn to throw. In Indianapolis, a two-night rebellion was set off in June 1969 after two police officers tried to break up a fight in the Lockefield Gardens Apartments in one of the city’s Black neighborhoods. A group of twenty people attacked the officers, slightly injuring them both. One lost his gun, his nightstick, and his badge. The crowd began to grow steadily from there, throwing stones at passing cars. In Akron, Ohio, in mid-August 1970, police came to the scene of a fight between two teenage girls near a custard stand. People threw rocks for several hours in response; one policeman was struck.[8]

When cops arrived to stop fights, residents did not perceive them as agents of peace and protection. Following the implementation of the national riot prevention strategy via the Safe Streets Act of 1968, which encouraged local police to initiate interactions with residents in targeted areas as a way to find potential criminals or rioters before they engaged in violent acts, cops and Black residents were brought into contact much more frequently. It’s possible the officers in Fort Wayne, Indianapolis, and Akron had the best of intentions when they intervened, that they hoped to prevent further injury and act as mediators. Yet their intentions mattered little to the residents involved. History and hard experience taught them that police were generally antagonistic, less likely to bring peace or protection and more likely to cause harm—either by beating residents (or worse), or by arresting them and carting them off to jail.

In the late 1960s, with the War on Crime in full swing, apprehending criminals or potential criminals, rioters or potential rioters, became the objective—the measure of “success”—of crime control in targeted communities. If police did not receive a tip about a neighborhood fight as in Fort Wayne, parks where young people of color congregated provided a ready-made site to patrol and possibly make arrests. Having no other pretense to stop, interrogate, and arrest Black youth, in mid-April 1968 the police department in York, Pennsylvania, began enforcing curfew at Penn Common after the wave of rebellions in other cities. Black children and teenagers liked to congregate in the park, and the cops wanted them out by ten o’clock or earlier. Police would chase, harass, and beat kids who refused to obey. A Black teenager described sitting with his girlfriend in the park in early July 1968, when all of a sudden, an officer pulled up and shined his flashlight in the young couple’s eyes. “Take that light off my face, we’re minding our own business,” the young man said. The officer got out of his car, billy club in hand, and told the couple to leave the park. He shoved his club in the teenager’s back, using it to push the young man as he escorted him and his date off the premises. This violent police encounter itself triggered violence. “Am I supposed to take that forever? What would you do?” the teenager asked a reporter. “Last night I threw a bottle at a cop.”[9]

Days after the officer disrupted the teenage date, on July 11, York police began their regular curfew enforcement routine, moving to clear about fifty Black kids and teenagers from Penn Common at 9:15 p.m. This time, the youths refused to leave. “Why do they have to disperse a group of Blacks?” one asked. “What’s wrong with congregating in the park?” When the police arrested two people, the rock- and bottle-throwing started. Twelve officers chased after various young people. Another violated proper procedure and fired his pistol in the air to scare them—and this action launched a five-day battle between police and Black residents, most of them in their teens and twenties. A reporter asked a male participant: “Why are young black Yorkers throwing rocks and bottles at policemen?” To which he replied: “Why do police hit people on the heads with their clubs?”[10] The cycle seemed clear enough, at least to this young man.

In Decatur, Illinois, Black teenage boys enjoyed drag racing on a strip that had been used for that purpose since 1964. In the summer, they would gather in nearby Mueller Park when the races were being held. White teens raced freely on a boulevard in the northern part of town, but police would regularly come to the southside park to surveil the city’s Black teens. Following a demonstration at the A&P store to demand jobs for Black workers on Thursday, August 7, 1969, the police decided to arrest the Black young people racing that evening. The cops were “mad” about the protest, one of the youths assumed, “so they came in here.” The Black tee...