ONE

Scotland

Baby James

Late sixteenth-century Scotland was a turbulent place. Riven by a jagged topography, divided in religion, fractured by inter-clan blood-feuds and threatened by foreign military intervention, leading barons were stabbed, poisoned, shot and blown up as factions jostled for power. As a result, baby James VI, born in June 1566, and crowned at the delicate age of thirteen months, was placed under secure guardianship in Stirling Castle, impregnably sited on a volcanic crag, a safe distance from Edinburgh.

Figure 1: View of Stirling Castle by John Slezer, c.1693. The twin towers of King James IV’s gatehouse, now much reduced in height, lie to the right of the royal lodgings which just appear behind the high curtain wall.

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

Stirling had been the focus of King James IV’s cult of grandeur, an architectural programme to provide a monumental setting for his court and power. Between 1496 and 1508 he had laid out some £12,300 creating a fearsome show-front to the castle with great gatehouse, flanking towers and finely built ashlar curtain walls, all now much reduced. Within these rose a large great hall and beyond, a suite of lodgings for himself. Like his brother-in-law, Henry VIII, James IV favoured what I have called, in an English context, chivalric eclecticism – a blend of architectural influences from the Middle Ages and Renaissance Italy. Arthurian romances, biblical stories, classical allusions, and heraldic devices jostled happily to create a distinctive eclectic look.[1]

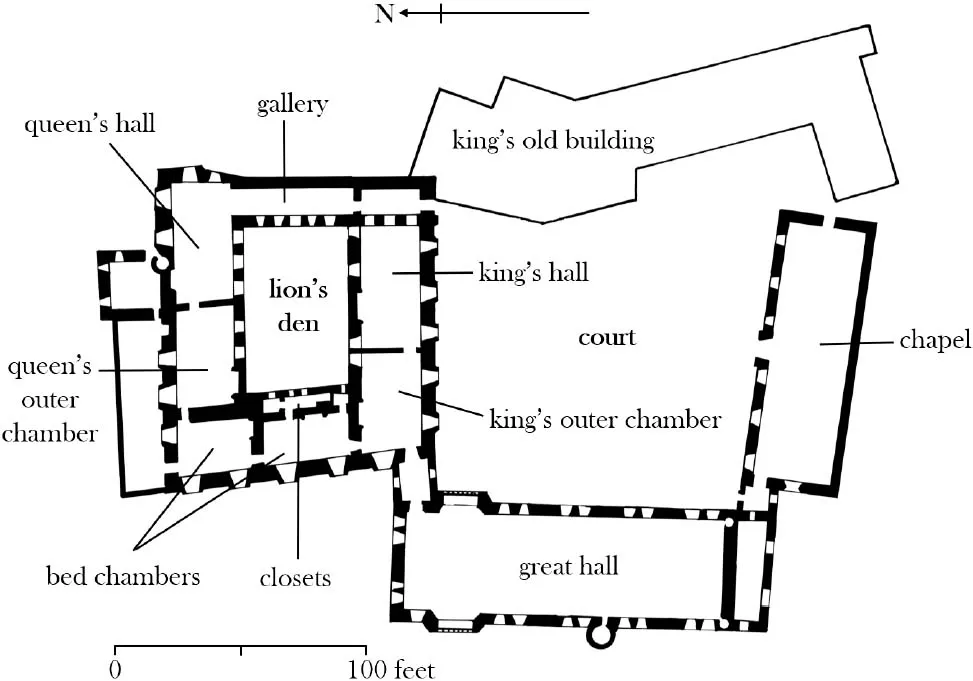

James IV’s Stirling contained no lodgings for a queen and when, in 1537, his son James V married Madeleine of Valois, the eldest daughter of the King of France, and subsequently, after her death, one year later Marie of Guise, work began on the construction of a new self-contained royal residence within the castle called the new work. This was a quadrangular block of lodgings round a tight courtyard sometimes known as the Lion’s Den. It was a simple, compact plan: from each end of a gallery the king’s and queen’s outer halls were reached and these led to great chambers for king and queen, a conjoined inner chamber and some small closets.[2]

This building was, for twelve years, the young king James VI’s home. It must have often seemed like imprisonment as his guardians fended off attempts to seize him from rooms which, although magnificent, retain to this day their iron window bars. Here the king received a harsh, demanding and thorough education learning Latin, he claimed in later life, before he could speak Scots. He amassed in his schoolroom a substantial library which was not just a princely ornament; it was the foundation of the king’s deep scholarship, of his love of debate and disputation.

In March 1578 the twelve-year-old king announced his intention to accept the responsibility of government in his own person and, in September 1579, accompanied by many nobles and several thousand horse, he processed to Edinburgh, making a triumphal entry. During the reign of David II (1329–1370), Edinburgh Castle had become the principal residence of the Scots monarchy and seat of government. It contained the state archives, treasury and the royal administration. Rebuilt and enlarged in the fifteenth century, it retained its premier position in the royal itinerary until the completion of the new lodgings at Holyrood in 1505. Nevertheless it had been the place of James’s birth in June 1566. His mother, Mary Queen of Scots, had been persuaded to retreat there for her confinement as a place of safety after the ghastly murder of her Italian secretary, David Rizzio, in her innermost room at Holyrood. The great rooms in the castle, fashioned by Mary’s grandfather, King James IV, were richly furnished for the occasion. There was a great chamber, a large inner chamber and a small cabinet or closet, where the queen gave birth to James VI.[3]

Figure 2: Reconstructed plan of Stirling Castle showing the royal lodgings at first-floor level.

© Simon Thurley

Although many years later James was to return to the room of his birth, and redecorate it for posterity, he showed little interest in the castle in 1578. After a tour of his capital, he made straight for Holyrood on the eastern periphery of the city, sited in its own hunting park and dramatically overlooked by the Salisbury Crags and Arthur’s Seat.

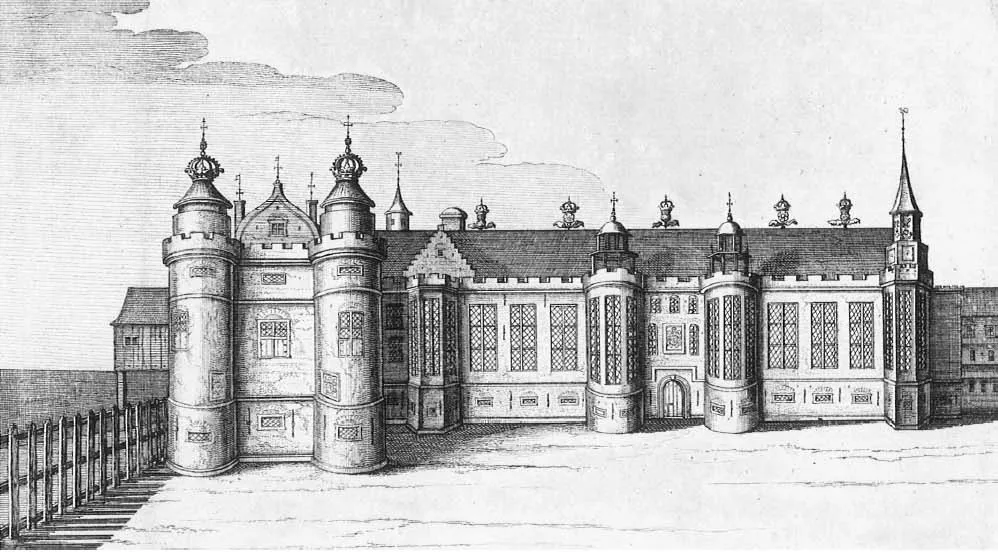

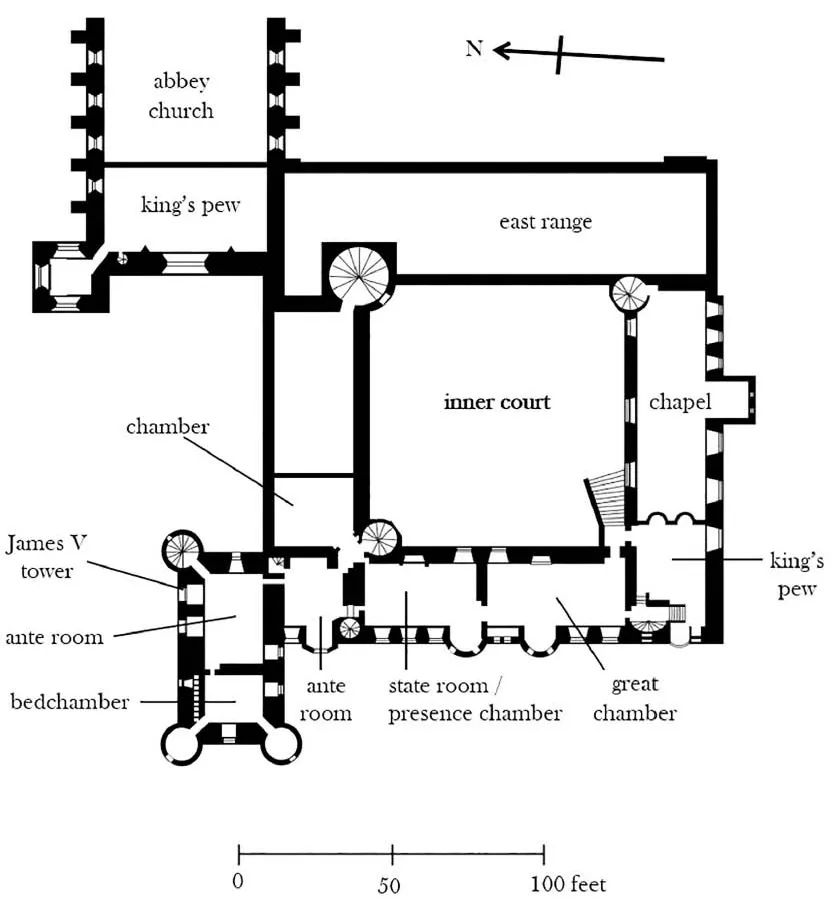

The Augustinian abbey at Holyrood, founded in the early twelfth century, had been a popular place for Scottish kings to stay but, in 1528, James V embarked on a reconstruction of the royal lodgings there, building a free-standing great tower of two storeys raised up on a vaulted basement. The king had an inner and outer chamber on the first floor and the queen an identical suite above. This sort of compact, fortified, tower lodging may have been appropriate for a teenage king fearful of kidnap but was not suitable for the 23-year-old monarch who was marrying a French princess. John Lesley, Bishop of Ross, who wrote A History of Scotland in 1570, describes what he calls the ‘bigging of paleicis’ in Scotland as having started because of King James V’s marriage and experiences in France.[4] Certainly at both Stirling and Holyrood the royal lodgings became less defensive, more magnificent and ‘bigger’ in the 1530s.

At Holyrood a splendid new west range created a glittering entrance front with big glazed casements, three bay windows, turrets and a crenellated parapet. The facade owed a debt to the large brick palaces of the Tudors, such as Greenwich and Hampton Court, but unlike England the royal lodgings were entered by a broad external stair in the inner court. From this there was access to the large domestic chapel on the south and the king’s outer or great chamber. There was then a second state room, which seems to have served as an audience chamber, and an ante room. The latter gave access to an inner chamber and to the great tower in which there was an ante room and the king’s bedchamber.[5]

A flurry of work put these lodgings into good repair for the young king James VI and his household as he arrived in 1579. Amusements were prepared: a billiard table was re-covered, new tennis balls bought, the ‘dancing house’ repaired and sand laid for the king to run-at-the-ring, the mounted test of skill where a ring had to be lanced by a galloping rider. Holyrood became his usual winter residence and a regular stop-off on his tour round his realm. After all Edinburgh was the largest town, the seat of government and the meeting place of parliament.[6]

Figure 3a: The west front of Holyrood in c.1649 by J. Gordon. The royal lodgings were in the tower on the left and the outer chambers on the right, lit by giant windows.

Public domain, sourced from Wikimedia Commons

Figure 3b: Reconstructed first-floor plan of Holyrood in the early seventeenth century, orientated to align with Gordon’s view of the west front.

© Simon Thurley

In 1580 the Scottish Privy Council decided to establish a formal court for James. The king’s first great favourite, Esmé Stuart, sieur d’Aubigné, Earl of Lennox, became the king’s lord great chamberlain and first gentleman of his bedchamber. Twenty-four gentlemen, all barons or sons of the nobility, served the king’s chamber in shifts of eight, as instructed by Lennox. All the other necessary departments were established including kitchens and stables, a particular interest to James. But the court suffered from a fundamental problem: cash flow. James had the title of a king but not the means to support his status. His court was chronically underfunded and in continual financial crisis. In 1584 Mary Stuart’s envoy Monsieur de Fontenay reported that ‘the King is extremely penurious. To his domestic servants – of whom he has but a fraction of the number that served his mother – he owes more than 20,000 marks for wages and for the food and goods they have provided. He only lives by borrowing’. James frequently turned to Queen Elizabeth I for financial support who, between 1586 and 1603, sent some £58,000 north to sustain the king and his household.[7]

Denmark

Soon after James’s court was established discussions began in earnest about his marriage. Royal marriages were international dynastic alliances in which countries established preferential trade links, military alliances and acquired diplomatic leverage. While James could expect a substantial dowry from an international match there was concern about whether the Scots court could sustain a queen financially. An English observer wrote that the king had ‘neither plate nor stuff to furnish one of his little half-built houses, which are in great decay and ruin. His plate is not worth £100, he has only two or three rich jewels, his saddles are of plain cloth’. In fact he could not see ‘how a queen can be here maintained, for there is not enough to maintain the king’.[8]

Although one of the options was a marriage to a French princess that would have helped cement the Auld Alliance with France and brought a huge dowry, the alternative was a match with Princess Anna, the younger daughter of King Frederick II of Denmark. Although this does not seem much of a contest, in the early seventeenth century Danish rule covered not only the territory that today bears its name but also Norway, much of Sweden, Schleswig and Holstein in what is now Germany and a constellation of islands in the Baltic and as far afield as Orkney, Iceland and Greenland. Through Holstein came membership of the College of Princes of the Imperial Diet of the Holy Roman Empire and so the King of Denmark was an Imperial Prince. Controlling access to the Baltic with a ring of mighty forts, and the finest navy in northern Europe, the Danes extracted tolls from merchant shipping making it an extremely powerful and wealthy monarchy.

In the expectation of relief from Danish tolls, it is no wonder that the merchant classes of Scotland wanted a marriage treaty with Denmark. It was ultimately also the match that James personally favoured. Anna, born in 1574, was fourteen, eight years younger than himself, tall, blonde, good-looking, and Protestant.

On 20 August 1589, in Copenhagen, James and Anna were married by proxy in a civil ceremony, and eight days later, James received the good news in Scotland. He immediately launched into preparations for the arrival of his bride and the church ceremonies that would see them man and wife in the eyes of God.

The 738 nautical miles from Copenhagen to Leith should have taken the sixteen Danish ships containing the princess and her trousseau some five days and so, believing them to have left on 1 September James anticipated seeing his wife within the week. On the 15th news arrived that, although the flotilla had sailed from Elsinore on the 5th, its whereabouts was now unknown. The fact was that the winds were gale force westerlies and the princess’s ships had been battered back to harbour four times, Anna desperately seasick. James, in a frenzy of anxiety, imagining the worst, sent a ship of his own to try and find her. Colonel Stewart found the princess’s ships sheltering off the southern tip of Norway. After fraught discussion it was agreed to abandon the attempt to reach Scotland and to make the crossing the following spring. The remaining seaworthy ships then took the princess north to Oslo.[9]

James, frustrated, impatient, and annoyed made a secret plan to go himself and rescue his queen. Secrecy was difficult because equipping five ships for such a voyage could not be done behind closed doors; nevertheless, he left Scotland and, three weeks later, arrived in Oslo, finally meeting his teenage bride. It was not long before Christian IV and his council of regency (he was only twelve) issued an invitation to the Scots party to spend the winter in Denmark; this James accepted, and he and his sparkling retinue of fifty or so attendants made their way overland to Elsinore.

The situation of Kronborg Castle at Elsinore is unforgettable. It sits on a sea-bound peninsular completely dominating the Straits of Øresund, the slender navigable artery between the Kattegat and the Baltic Sea from which the Danish kings harvested a toll from passing ships. The castle had been built in the 1420s to enforce the dues and was an unusually regular square of ten-metre-high masonry, inside which was accommodation for a garrison and the king. Kronborg remained a severe military installation until 1574 when King Frederick II, Queen Anna’s father, resolved to transform it into a great palace.

Frederick was fascinated by architecture and recruited designers and craftsmen from Germany and Flanders to realise his ambition. Entered through a series of Renaissance-style gates, the palace was arranged round the inside of the medieval courtyard. To the south, on the first...