![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Religion and Ritualized Belief

Contemporary Views and Traditional Practices

YUDIT KORNBERG GREENBERG AND HANNA CODY

INTRODUCTION

The discourse on hair and religion reveals the meanings and dialectical relations that exist between the physical body and the “social body.”1 Hair as an extension of male and female bodies has been represented, modified, disciplined, and celebrated in ancient as well as contemporary societies and religious communities. What sets hair apart from the rest of human anatomy is malleability; hair, unlike other body parts, can be visibly physically altered and adapted: it can be grown, cut, shaved, colored, styled, and covered in numerous and creative combinations. Thus, hair becomes an ideal body part for self-expression, a means for publicly expressing one’s social and/or religious identity, and because of its perceptibility and material plasticity, an important symbol of sexuality. The juxtaposition of hair and the sexualized body renders its manipulation subject to prescription and control by religious and social institutions alike, but aligned with questions of social status and gender, this dynamic plays a particularly pivotal role in the rituals and rules of self-presentation assigned to members of religious groups.

In this chapter, we examine the paradoxical category of hair in religion and society in the modern age as both a source of beauty and admiration as well as a source of impurity and shame. Hair presentation and maintenance, whether subject to traditional or contemporary religious or cultural influence, is important because hair functions as a means of representing individual and group identity. Religious rituals pertaining to hair, along with contemporary social trends, have continued to shape and construct our physical body and our identity. However, religious discourse on whether hair should be kept, cut, or covered is often determined by the cultural contexts in which the religious beliefs and practices develop. For example, the current banning of certain religious dress codes in some European countries relating to women’s hair covering raises questions about veiling as an example of women’s oppression and a mechanism for social control imposed by patriarchal social structures.2 However, it is important to note that discourse on women’s hair as found in scriptures such as the Bible and the Qur’an is neither extensive nor prescriptive. Moreover, men too are subject to a range of rules and conventions regarding the control of their hair as a crucial marker of religiosity, masculinity, and patriarchal authority. While again not mandatory, these nevertheless exert considerable pressure to conform.3

The state of hair in religion in the modern age is indeed a complicated subject and draws upon various social, cultural, and historical factors that often take on new meanings and significance, particularly in diasporic contexts. Based upon multiple interpretations of hair in several religious traditions—Sikh, Hindu, Jewish, Christian, and Islamic—this chapter explores the shared symbolic potency of distinctive religiously motived practices relating to head and facial hair. The examples used are not exhaustive and do not include important rituals and conventions relating to the shaving or other management of body hair. Rather, the aim is to examine the scriptural foundations and modern refigurations of head and face hair and its manipulation that continue to mirror and mold traditional and modern faith-based identities. For heuristic purposes, much of the discussion is organized along gender lines, but the emphasis is dialectic: the relational contradistinctions of men’s and women’s cutting, growing, display, and concealment of their hair; the tension between tradition and modernization; and the emergence of modest fashion as an expanding sector within a global fashion industry.

HAIR AS METAPHOR OF RELIGIOUS/SOCIAL ORGANIZATION AND CONTROL

While differently motivated, men’s visible control of their hair across religions and cultures can be located within a symbolic grammar of social interaction central to the institutions of a given society and the establishment and reinforcement of social, religious, and physical boundaries. Anthropologist Paul Hershman in his notable essay on hair symbolism among Punjabi Sikhs and Hindus, organized these coded relational meanings thus:

| PROFANE (non-sacred) | | SACRED |

PURE | Hindu men hair cut | → | head shaven |

IMPURE | Women hair never cut | → | hair loosened4 |

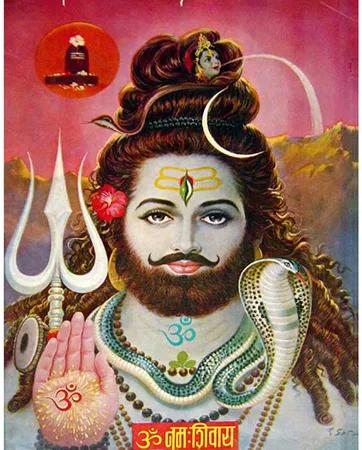

In this context, scholars Hallpike, Leach, and Olivelle have argued that hair in Hinduism is indicative of social control,5 sexuality, taboo/sacredness,6 and as a marker of social separation/inclusion, “a multifaceted complex consisting of sexual maturity, drive, potency, and fertility.”7 In Hinduism the god Shiva, from whose head the Ganges is purported to flow, is often depicted seated with his hair arranged with a stream of water flowing onto a lingam–yoni—a statue that represents Shiva and his wife, Parvati—that symbolizes the joining of male and female sexual organs. Thus, the arrangement of Shiva’s hair is both phallic and the source of his concentrated sexual potency from which life springs.8 Through this lens, the hair of mortals, especially women’s hair, must be revered as well as feared.

Within a relational system of potent hair symbolism, head shaving in South Asia—whether in Hindu, Buddhist, or Jain traditions—serves as an initiatory ritual that involves either a permanent or an extended period of separation and marks the transition into a new phase of life. Hair that is removed or left uncut serves as a marker of celibacy, a detachment from social norms of appearance and the transcendence of the physical and social boundaries they articulate, particularly relating to sexuality.9 The annual liturgical shaving of hair for Hindu ascetics (sannyasins or renouncers) reaffirms their commitment to their vows and their spiritual goals. For others, such as sons following the death of a parent, widowers during periods of mourning, and those undergoing initiation ceremonies, the period of separation from society is briefer.10 Vedic students returning from a period of separation and who have left their hair uncut are ritually shaved prior to a final ceremonial bath in preparation for marriage and the assumption of their new social role and status.11

FIGURE 1.1: Lord Shiva. Bazaar Art Poster 1940s. Source: Columbia.edu. Wikimedia/Public Domain.

In most if not all religions, shaving practices are central to rites of passage, initiation ceremonies, and rituals relating to the individual’s perceived level of purity; their purpose is to signal clear distinctions based on identity, such as affiliation with a religious community, age, sex, gender, or level of social inclusion or exclusion (either temporary or permanent). For example, Muslim men making the hajj (pilgrimage) to Mecca are required to shave their head and body hair and cut their nails as a form of ritual cleansing. Having fulfilled their highest religious goal, they are then free to regrow and groom their beards as a symbol of their religious and social authority and sexual maturity.12

The growing of young boys’ hair prior to its ritual cutting can also be understood within this symbolic framework of social transition and initiation into structures of masculine social control. Since the seventeenth century, the practice of keeping a male infant’s hair uncut until the age of three has become popular and remains prevalent in Hasidic Jewish communities. This hair-cutting ceremony is called upsherin (Yiddish: lit. “shear off”) and can be related to the injunction in Leviticus 19:23 prohibiting the eating of the fruit that grows on a tree for the first three years. The young boy, like a healthy tree produces fruit, will grow in knowledge and will become a Torah scholar. For the ultra-Orthodox, only the hair on the head is sheared; the earlocks or pe’ot (plural)—the hair in front of the ears extending beneath the cheekbone—are kept per the biblical injunction in Leviticus 19:27, “You shall not round off the pe’at of your head.” For others, both the hair on the head and the sidelocks are cut off during the ceremony. As part of the upsherin ceremony, it is also a custom to weigh the shorn hair and donate it to charity.

In the Hindu faith, the ritual of cutting a young boy’s hair between the ages of one and three (chudakarana or mundan) is similarly recognized as an important sacrament (samskara).13 Sometimes, a small patch of hair (tonsure) will be left on the back of the head, again as a means of maintaining health and leading to overall longevity in part derived from a statement made by Vasistha (a Vedic sage), “Life is prolonged by tonsure; without it, it is shortened. Therefore, it should be performed by all means.”14

For laymen of Jewish, Muslim, and Christian faiths, the relational shaving and or growing of the beard is a primary focus because it occupies an important site of incubation for the display of masculinity, virility, and patriarchal authority. The visible control by adult men of their hair symbolizes their public roles as husbands, fathers, and devotees in relation to “others”—unmarried and younger males and male children, women, those of other faiths, and nonbelievers. Such control inflects all other manipulations, and forms the basis from which they derive their meaning and significance.15

Anabaptist Mennonite men in North America keep their hair short, their upper lip shaven, and grow full beards to signify their pacifist beliefs, their sexual maturity, and their marital status. In the Bible in Leviticus 19:27, we read about the prohibition applied to all men against shaving their beard with a razor or removing the hair at the corners of the head. The reason for the prohibition of shaving is not stated in the Bible, but the rabbinic authority, Moses Maimonides (1135–1204), comments that this biblical law indicates that the Israelite priests rejected the common practice of “heathen” priests who shaved their beards and Hasidism, the popular mystical movement that originated in eastern Europe in the eighteenth century, adheres to the kabbalistic view of the beard as an earthly symbol of God and, therefore, mandates the maintenance of long beards and sidelocks. However, most westernized Jews do not wear beards, including many Orthodox rabbis, and despite attempts to proscribe shaving with a razor, in recent decades it has also been ruled permissible to remove facial hair with scissors or an electric shaver.

Faegheh Shirazi evidences disagreements between Islamic scholars, clerics, and experts in sharia law as to the interpretation of the Qur’an’s dictates regarding the treatment of men’s facial hair.16 Each Islamic sect offers different and conflicting perspectives on the wearing of beards and mustaches, desired lengths, and the finer details of grooming depending on the regional geopolitics and cultural traditions extant at different times, but Shirazi argues, “nowhere in the religious literature is it stated that every Muslim man must grow a beard … while growing a beard is generally recognized a virtuous act, it is not mandatory.”17

Anthropologist Christopher Hallpike understands these socially sanctioned practices in terms of symbolic equivalence: hair control equals social, that is, primarily sexual, control.18 In most religions, men’s head hair is kept short in contrast to women’s who, as we shall see, are largely required to keep their hair long and controlled in some way by braiding, knotting, or most notably, covering to symbolize their shared participation in socially sanctioned structures of sexual expression, particularly marriage. There are exceptions. But as Indologist Patrick Olivelle points out, it is these contradictions that illustrate the extremely “loose” nature of hair’s ...