- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

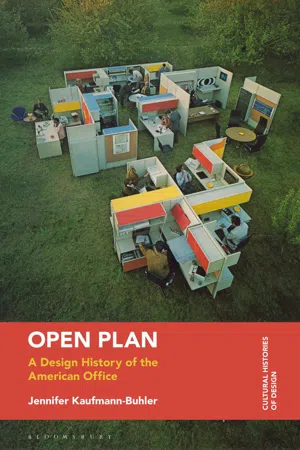

Originally inspired by a progressive vision of a working environment without walls or hierarchies, the open plan office has since come to be associated with some of the most dehumanizing and alienating aspects of the modern office. Author Jennifer Kaufmann-Buhler traces the history and evolution of the American open plan from the brightly-colored office landscapes of the 1960s and 1970s to the monochromatic cubicles of the 1980s and 1990s, analyzing it both as a design concept promoted by architects, designers, and furniture manufacturers, and as a real work space inhabited by organizations and used by workers.

The thematically structured chapters each focus on an attribute of the open plan to highlight the ideals embedded in the original design concept and the numerous technical, material, spatial, and social problems that emerged as it became a mainstream office design widely used in public and private organizations across the United States. Kaufmann-Buhler's fascinating new book weaves together a variety of voices, perspectives, and examples to capture the tensions embedded in the open plan concept and to unravel the assumptions, expectations, and inequities at its core.

The thematically structured chapters each focus on an attribute of the open plan to highlight the ideals embedded in the original design concept and the numerous technical, material, spatial, and social problems that emerged as it became a mainstream office design widely used in public and private organizations across the United States. Kaufmann-Buhler's fascinating new book weaves together a variety of voices, perspectives, and examples to capture the tensions embedded in the open plan concept and to unravel the assumptions, expectations, and inequities at its core.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Open Plan by Jennifer Kaufmann-Buhler in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Design & Interior Design. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Designing Hierarchy

In the 1980 film 9 to 5, Lily Tomlin, Dolly Parton, and Jane Fonda played three white-collar workers who kidnap their “sexist, egotistical, lying, hypocritical bigot” boss, played by Dabney Coleman. In his absence from the office, they transform the bureaucratic and deeply sexist corporate culture into a more supportive organization with a host of new feminist policies and benefits including flexible hours, job share, equal pay for equal work, and in-office daycare. Over the course of the movie, office design serves as a direct expression of this transformation. At the start of the film, the office is a dull and monochromatic bullpen with rows and rows of tidy desks arranged in a grid, a spatial reflection of the top–down organizational culture of the corporation. By the end of the film the three women had transformed that same office into a new open plan, featuring a looser arrangement of desks in small groupings separated by low brightly colored orange and yellow partitions. Notably, the image of the new open plan in the film also emphasizes the diversity and inclusiveness of the space—the view of the newly designed office prominently features women, workers of color, and even a worker in a wheelchair pulling up to their open plan workstation reinforcing the idea that this workplace is an entirely different one not only spatially, but also culturally. This symbolic intertwining of an inclusive organizational culture and the open plan office design in the film reflects the image of the open plan as a naturally progressive office design solution and an expression of a more egalitarian organizational culture.

This chapter traces these changing ideas about hierarchy and office design from the conventionally designed offices of the mid-twentieth century with its rigid expression of hierarchy and status to the new and supposedly more inclusive open plan. Architects and designers of the period often treated status in office design as a neutral expression of organizational position and status, but I argue that office hierarchies of this era were intertwined with the long history of discrimination in the workplace, particularly in terms of gender, race, and ability. Advocates in the late 1960s viewed the new open plan as a complete reimagining of organizational culture, management theory, and the office itself, particularly in its rejection of hierarchy and status as organizing structures of the office. Echoing the emerging ideas in management theory of the 1960s, architects and designers promoting the open plan envisioned a future in which workers would have greater ownership over their work and work process, which in turn would benefit the organization by increasing productivity, efficiency, and creativity. Rather than imagining the organization as a system of rationalized boxes reporting up the chain of command (as represented in an organizational chart of the era), new management theory described the modern organization as a flatter system in which all the parts of the organization were important contributors to the larger goal. For proponents of the open plan, the new office concept was the spatial manifestation of this larger transformation in the structure of work that promised a more egalitarian culture.

Even as the open plan projected an image of greater inclusivity, hierarchy was always an integral part of the planning process for the open plan. Though its advocates often described the benefits of worker participation in office planning, the open plan was typically implemented in ways that codified and reinforced the positions, priorities, and preferences of those in power and often left out altogether the experiences and needs of lower level support staff and service workers, who rarely had the opportunity to participate in the design process in a substantive way. Recognizing the long tail of discrimination and exclusion embedded in hiring and promotion practices in American organizations throughout the twentieth century, this system effectively prioritized the voices of predominantly White men in professional roles while ignoring the voices, perspectives, and needs of marginalized workers in lower level positions including women, workers with disabilities, and workers of color. Despite its progressive and countercultural image, the open plan in fact reinforced organizational structures and systems of inequality through its design and usage.

Postwar Corporate Hierarchy

The postwar period saw an enormous growth in the design and construction of new corporate offices in the United States.1 Rather than rehabilitate, remodel, or update their older buildings, American companies of that era invested enormous resources in constructing entirely new office buildings to suit their rapidly expanding organizations. Whether located inside of a towering skyscraper in the central business district of a major city or in a sprawling corporate office in the suburbs, these new offices reflected the organizational priorities and needs of the time. As Louise Mozingo argues, through their design, these new corporate headquarters of the postwar era needed to: serve as an architectural symbol of the organization, impressing investors and banks and conveying their “corporate trustworthiness”; attract and keep top executives, ensuring that those corporate executives felt a connection to the organization as a whole; and reassure the public that their fears about the excessive power of large corporations were unfounded. According to Mozingo, the corporate architecture of the postwar became the public image of the organization, and a “tangible corporate persona.”2 Further, as Alexandra Lange argues, corporate office design of the postwar was not simply “a matter of dressing the old building in a new glass-and-steel wrapper,” it was an “overhaul” of the organizational structure by way of architecture.3

Architects and designers planned the interior space of new corporate offices around the organizational structure in explicit ways. First, they designed these new offices based on the formal departmental divisions, breaking up the organization into its constituent parts as conceptualized by the organizational chart and arranging the various corporate divisions around their functional and hierarchical relationships with other units. Within each department, the division of space reflected the inner workings of that department as well as the functional and hierarchical relationships among workers. Office planners typically provided workers in elevated positions a private office while they placed workers in lower-level positions, particularly those in technical and clerical roles, in an open “bullpen.” Mapping the interior, architects and designers created detailed standards that allocated space, furniture, and accessories based primarily on the organizational status of each worker. The interior standards established for a particular project rationalized the allocation of space and amenities across the organization to reflect differential status from the topmost executives to the lowest-level clerical workers.4 In her study of a single organization, sociologist Rosabeth Moss Kanter found a “clear system of stratification” in the conventional office materialized through furniture design, stretching from the metal framed desk with a wood top, to solid wood, and finally to a marble top for those at the top of the organization.5 Desks were not the only attribute of distinction; journalist Vance Packard described the importance of office size and location as well as all of the other accessories and elements of décor that were tied to status including: lounge furniture, ashtrays, filing trays, carafes, carpets, drapes, and even art. Within this elaborate system of office hierarchy, each change in organizational status merited new office décor such that nearly every promotion required a parallel change in office space.6

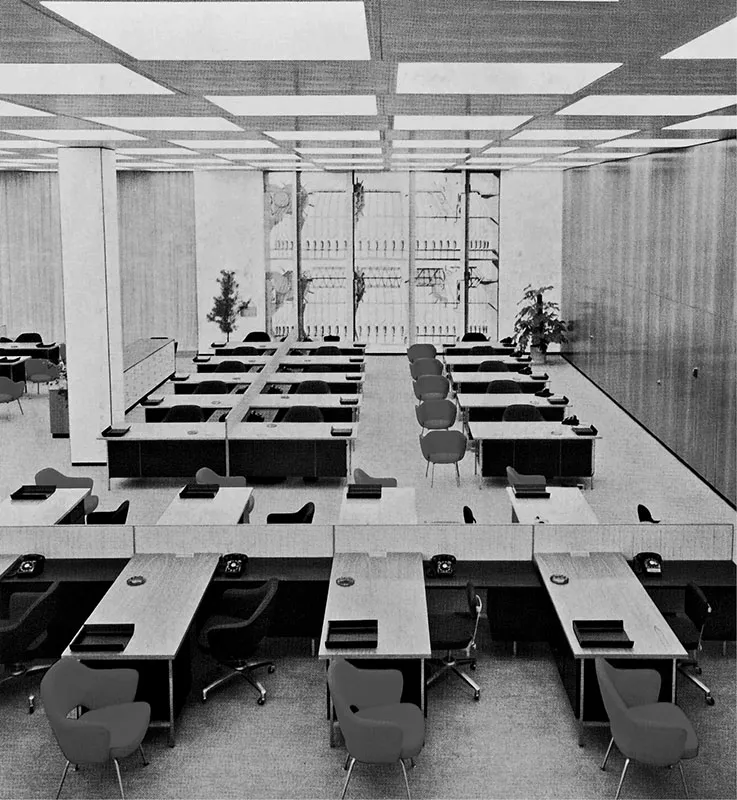

In their corporate office designs, postwar American architects and designers such as Eero Saarinen, Charles and Ray Eames, and Florence Knoll championed a total design approach, applying a modern design aesthetic in a consistent and predictable way as a spatial and material expression of organizational efficiency and modernity. For example, in her work leading the Knoll Planning Unit, designer Florence Knoll created meticulous plans for her office designs. Figure 4 shows an office interior featured in a Knoll catalog, showcasing the orderly arrangement of Knoll desks with their clean geometric forms providing an elegant contrast with Eero Saarinen’s organic office chairs. According to Bobbye Tigerman, Knoll’s approach to design, which used the iconic pieces from the Knoll company’s furniture line, became a “visual code” of the modern office.7 This style of corporate modernism became the common visual and material lexicon of organizational hierarchy and management through the midcentury in the United States.

Figure 4 Sales office for Deering, Milliken and Co. in New York City, designed by the Knoll Planning Unit, featuring Florence Knoll desks and Eero Saarinen desk chairs, 1958. The image illustrates the meticulous office planning that came to define the modern corporate interior.

Source: Image Courtesy Knoll Archive.

Architects’ and designers’ emphasis on creating a rationalized and carefully planned corporate interior explicitly designed around organizational hierarchy was a material expression of an idealized and fetishized corporate bureaucracy. In White Collar, C. Wright Mills describes the office as a “symbol factory” where every action and decision of the organization was rendered material through pieces of paper circulating through the office from one clerk to another, from one floor to the next.8 From the early-twentieth century through the postwar period, this circulation of paperwork was also a central focus in office design. Manuals on office layout and management emphasized the importance of arranging clerical staff around the idea of paperflow, ensuring that each worker’s placement fit with the circulation of paperwork (forms, memos, processes) snaking through the office from worker to worker and division to division.9

This design process awarded workers in the upper level positions with the elaborate perquisites of organizational status and treated low-level workers as operational gears in a bureaucratic machine. The workspace was an explicit manifestation of hierarchy, status and position. As Lange argues, this meant that “one’s job was visible with a glance at the purpose built desktop; its importance to the firm visible with a glance at its proximity to the powerful.”10 The postwar corporate office was thus conceptualized as a materialization of the working process, a tool in the circulation of work and information, and an outward expression of organizational hierarchy.

Cultures of Conformity and Discrimination

Workers were present in this system of circulating paper, but architects, designers, and managers often treated them as movable and interchangeable components within the larger space of the office and the organizational bureaucracy. This way of thinking about the organization as a system constructed predominantly of paperwork was not new or unique to the postwar era; for example in his research on the expansion of clerical work in mid-nineteenth century America, Michael Zakim analyzes the numerous ways in which the production and circulation of bureaucratic paperwork came to define modern capitalism, modern office work, and the design of the office itself.11 Throughout the modern era, office design has been conceptualized by architects, designers, and managers as an idealized manifestation of the corporate hierarchy and more specifically as a system composed of workflows, job titles, and organizational relationships embodied by the corporate organizational chart. But the process of designing new corporate buildings in the mid-twentieth century with newly defined space standards created a fresh interpretation of the rationalized and standardized organizational hierarchy. Postwar architects imagined the corporate hierarchy, the organization, and its workers as abstract entities, and treated the new corporate office as the conceptual and material matrix that would draw these disparate components together and create a rational, cohesive, and orderly structure for their containment. Interior layouts neutralized the human workers into movable and interchangeable widgets in the organizational system, and this approach to design reinforced an image of the workplace as one that was inhabited by a universal and illusory worker whose body, identity, and individuality had been scrubbed away.

As Aimi Hamraie has argued in their book Building Access, architects and designers have a long history of designing around a universalized figure whose “neutral body” is meant to stand in for an average and idealized user or inhabitant. Hamraie refers to this universal figure at the center of architecture and design practice as the “normate” user whose average body is not only used as an imaginary template for the design process, but also as a kind of prescription of the idealized user who was typically conceptualized as a White, male, and nondisabled user. In the postwar period, women were increasingly included in human factors charts and architectural planning, yet like their male counterpart, her ide...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-title Page

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Designing Hierarchy

- Chapter 2 Managing Change

- Chapter 3 Negotiating Privacy and Communication

- Chapter 4 Personalizing the Workstation

- Chapter 5 Supporting Technology

- Chapter 6 Facilitating Movement

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Index

- Copyright Page