![]()

Chapter 1

Imperial Europe at the Dawn of the Twentieth Century

In the summer of 1898, a group of prominent Dutch women held an industrial fair in the Hague, capital of the thriving imperial nation of the Netherlands. Their goal was to showcase the nation’s achievements and in particular to display women workers in modern industry, the arts, and crafts. The fair also featured Dutch life beyond Europe, making the exposition an act of national pride—a “national cause,” the sponsors called it. Outside the main buildings, the fair put on view a model Indonesian village, complete with local peoples imported from the Dutch colony to display folkways and indigenous life. They played Indonesian music on the traditional instruments of the gamelan, cooked Indonesian food using peanut and other novel sauces, and dyed the celebrated batik fabric under the curious eyes of Dutch and other visitors. Such a display brought the colonies to the metropole or European homeland—in this case, the Netherlands. It testified not only to Dutch imperial holdings at the turn of the century but to the global reach of Europe in general.

International fairs with exhibits from around the world were a regular feature of imperial life in Europe, which defined itself in terms of its global power at the dawn of the twentieth century. Europe’s colonies abroad during this time were extensive. Great Britain, France, and other European powers controlled great swathes of territory from Africa and the Middle East to India and the Pacific islands. These fairs showcased the cultural fruits of empire and often had a profound effect on those who attended them. From the Crystal Palace Exhibit in 1851 in London to the Universal Exposition in Paris in 1889 where the Eiffel Tower was first displayed, millions of European attendees were often astonished at what they saw. Sir William Gilbert, the English librettist, found his world turned “topsy-turvy” after viewing an exposition that featured Japanese products and wrote the renowned operetta The Mikado (1885) in response. Gilbert was among the many Europeans who wove the materials that came from beyond Europe—whether manners, musical sounds, patterns in art and poetry, or products like chocolate—into their culture at home. In so doing, he along with his collaborator Arthur Sullivan became celebrated—both of them knighted by Queen Victoria. Their accomplishments, combined with global expositions enhanced pride in the individual nations that exhibited them—whether in Paris, London, Rome, or Berlin. The age of empire in Europe was also a period of soaring patriotism and intense, even militant nationalism.

The world’s fairs of the turn of the century took place in a Europe that was modern and complex. The expansion of industry produced class divisions between the wealthy, who sponsored world’s fairs, and the workers, who labored in them and who—as in the case of women workers at the fair in the Hague—sometimes protested the long hours and very low pay. From the diamond cutters who processed the gems from mines in South Africa marketed by the Dutch company de Beers to the hands in textile factories, the women operatives displaying their skills at the fair represented the large and vocal working classes of the time. To make matters more complex, gender roles were changing along with the development of this kind of class awareness. The middle-class Dutch women who orchestrated this fair and took on public responsibilities signaled the gradual evolution of gender roles. Changing gender roles and the swelling of working-class protest that veered into calls for socialist revolution and the overthrow of the capitalist system of private property upset many. Thus, although the industrial fair in the Netherlands attracted tens of thousands of visitors, it unwittingly showcased some of the burning issues of the day.

Even as the fair was in full swing, discontent arose over the economic downturns that were part of European industrial and agricultural modernization. Not only did hard-pressed workers organize strikes and political parties for working people, but millions migrated to find opportunities elsewhere. New nation-states such as Australia, Argentina, Canada, and the United States attracted newcomers, many from hard-pressed peasants seeking economic opportunity. Experiences of migration were not always success stories, however. Many an emigrant from Europe found life no better elsewhere, although millions more were glad to escape. At the Dutch women’s fair, the Indonesians who served luscious local food or who played Indonesian instruments fell homesick and demanded to return home even before the fair was over.

In 1900, still another international fair took place in Paris to open the new century. Buildings rose to house the exhibition, many of them in the experimental “art nouveau” style that remains a vivid architectural element of the city today. The year 1900 was part of a period that later came to be called the “Belle Époque” or the “good old days.” Europe was at the top of its game. Its prosperity was rising; inventions like the bicycle, telephone, and electric appliances were starting to make life even better; and city life offered amusements found in newspapers, café leisure, vaudeville shows, and even the young film industry. Population soared as prosperity helped many live longer.

Yet Europeans, leading the way in inventions and new ideas, were entering one of the most destructive periods in history. As the century opened, militants assassinated an alarming number of heads of state and bombed stock exchanges and other institutions of European power, terrifying the ruling classes. Many nations teemed with determined nationalists demanding more conquests, and relationships among the Great Powers were increasingly raw because of competing imperial ambitions. Activists and ordinary people in colonized regions around the world resented European pretensions to power, which caused them to explode in violent resistance. National ambitions, bitter differences among classes, and growing violence were as much part of Europe’s story in the early twentieth century as were Europe’s innovations as displayed in festive world’s fairs.

Europe’s Peoples and Nations in the Global Order

In 1900 Europe had already embarked on a course that would eventually make it more densely populated and urbanized than any other of the world’s regions (see Map 1.1). It had healthy industrial and agricultural sectors, which experienced continuing economic growth despite mounting global competition. Benefiting from sufficient food and from expanding industrial power, the European population came to live longer but also to demand an even better standard of living. Leaders of the “Great Powers” of Europe had increasingly to address working-class aspirations, even as they simultaneously engaged in a contest among the nations for commercial markets and global influence that they believed crucial to maintaining national strength abroad and social peace at home.

Map 1.1 Europe in 1900. Europe in 1900 was a collection of relatively small and a few large nation-states, which only in the late nineteenth century had become more economically powerful than India and China. Compact and relatively unified, the great European powers were also armed with destructive modern weaponry and fortified by mass armies. Most rulers believed in their nation’s superiority and successfully promoted nationalism among their people.

Prosperity for States and Society

Industrial and agricultural progress of the previous century formed the backbone of Europe’s burgeoning population of 450 million in 1900. Europe’s innovators had fostered mechanized agriculture, created modern transportation and communications systems, and mounted chemical, steel, and electrical power systems—all of which served to support a growing number of people. Advances in medicine increased life expectancy by nine years between 1850 and 1900. The largest in Europe, Russian population more than doubled, rising from 73.6 million in 1861 to 165.1 million before World War I. German population also rose dramatically percentage wise, growing 25 percent between 1890 and 1910 to reach sixty-five million, and Great Britain’s population grew from thirty-four million to forty-two million during the same period. Only France bucked this trend, with a population that had increased only 40 percent over the entire course of the nineteenth century in contrast to the quadrupling of citizens in Britain over the same period. France’s failure to grow at the same rate as the rest of Europe had several causes, among them its early use of birth control and its series of tumultuous revolutions that began in 1789 and continued for almost a century. Machinery reduced the number of hands needed on small farms and large estates alike, sparking migration. Thus cities like Berlin grew from 1.5 million to 2.5 million between the 1890s and the outbreak of war in 1914, as people sought opportunity in urban life.

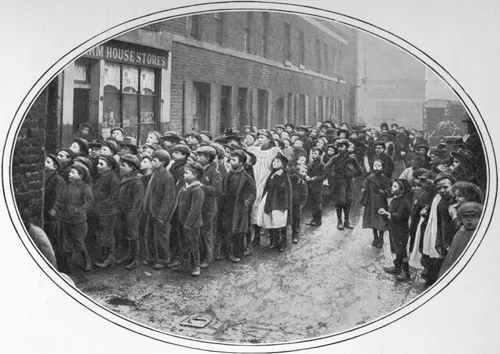

Modern Europe’s prosperity was spread very unevenly among socioeconomic groups or classes. Most European countries had aristocracies with privileges and economic wealth. They controlled urban property and landed estates, which were sometimes endowed with the natural resources such as ore and coal that industry craved. At the other end of the social ladder was the vast majority of Europeans employed on the land, in the mines, and in the factories that processed raw materials into goods like steel. It was the ups and downs of advancing industrialization that put people out of work and underemployed them at varying moments in their lives. Out to make a profit for themselves, the wealthy classes often paid far less than a living wage to their workers. Queen Victoria, who died in 1901 as the century opened, was appalled at the poverty of her people. Early in her regime, she had noted on visiting one industrial region: “In the midst of so much wealth, there seems to be nothing but ruin.” Depressed at the sight, she remarked on the “wretched cottages” and sickening “black atmosphere” of factory towns in which “a third of a million of my poor subjects” live1 (see Image 1.1). Still, many in the population deferred to the aristocracy and revered the monarchy: the young Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands was the prized visitor to the Dutch women’s industrial fair.

Image 1.1 The Working Poor: London Children Lined Up for Food, 1900. In 1900, Britain was an imperial powerhouse, but one with great inequality. The working-class family was often large because of the decline in infant mortality, allowing urban parents to use their young children in household tasks such as fetching water, scavenging for discarded goods, and minding young siblings. Reformers worried about the medical care, education, nutrition, and parenting poor children received out of concern for national strength in an age of intense international rivalry. Would you say that these children need improvement? © The Print Collector/Getty Images.

Europeans were divided by class, and they were also divided into competing nations. Rich or poor, the majority of them inhabited the six major, strikingly different empires that dominated the international scene as the twentieth century opened. Each of the empires actually had an emperor, except for France, which was a republic with a president and prime minister (though its former nobility remained rich and influential). The Ottoman Empire, ruled by a sultan from Constantinople, had a system of powerful ministers running different regions of its extensive Mediterranean holdings. France, Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Britain allowed the majority of white men to vote in national elections before 1914, while the Ottoman and Russian empires remained autocracies. The empires of the Ottomans, the Habsburgs of Austria-Hungary, and the Romanovs of Russia comprised mostly adjacent lands, while the French, British, and Germans ruled over territories some of which were oceans away. Smaller states like the Netherlands, Portugal, and Belgium held significant territory abroad. The empires also differed in the extent of industrial modernization and in the size of their armies and navies, with the Ottomans, Russians, and Habsburgs trailing their western neighbors. The common denominator to all the empires was that each was multiethnic, with the various ethnicities often held in place by the threat of force or by actual brutality.

Great Britain: Greatest of the European Powers

Britain relished its accomplishments. At Queen Victoria’s death in January 1901, Great Britain claimed to rule 25 percent of the world’s landmass and 20 percent of its population. Its proudest achievement was its empire in India, while colonies in Africa were becoming increasingly important with the discovery of extensive natural resources such as rubber, gems, gold, and other precious metals. Britain had also controlled Ireland for 200 years and Egypt for 20, but nationalist movements in each region were rising to contest British exploitation. The need for fuel in home lighting and in the growing automobile industry spawned a drive into the Middle East in pursuit of oil. In the nineteenth century, Britain had been an industrial pioneer in textiles, railroads, and metallurgy, trading its manufacturing goods around the world in exchange for raw materials. However, the British had lost their lead in innovation, lagging behind the advances taking place elsewhere in electricity, chemicals, and transport. Nonetheless, Britain’s worldwide reach made it the leading global banker, with London an international hub that would remain powerful into the twenty-first century. As control of capital became increasingly important to financing industry, Britain’s lead in global banking ensured that its upper class would remain wealthy despite challenges in manufacturing.

Headed by a constitutional monarch, Britain had a well-defined social structure, topped by an aristocracy with incredible staying powe...