![]()

1

Michael Balcon

The public dismay which greeted Michael Balcon’s decision to sell the freehold property and studios at Ealing to the BBC was obvious. No one had seen it coming. Britain’s best-known and best-loved film company was vacating its long-term home and seemingly abandoning its identity.

‘The news about Ealing Studios hit the Street like a blow in the face from Rocky Marciano. This was one of the best-kept secrets in a trade where little of consequence happens without whispers getting round,’ wrote Bernard Charman, editor of the Daily Film Renter, in his ‘Wardour Street’ commentary column the day after the deal was announced.1

Balcon tried to reassure the public and industry alike that Ealing Studios would soon have a new home. This new home wasn’t going to be at Ealing, though. The ‘stronghold’ at which films from Whisky Galore (1949) to Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949) had been made was about to be lost. Balcon and his business partner, Major Reginald Baker, had already agreed that the entire contents of the studios would be put up for sale by auction.

It is instructive to read the exhaustive press coverage about the sale. National newspapers and film trade magazines alike queued up to express their alarm and disappointment that Ealing’s very particular type of British films would no longer be produced at their old home in this ‘prim little suburb of West London’.2 As Tribune put it, this was ‘a national calamity’. What made the sale to the BBC all the more worrying was the fact that the BBC and ITV had already ‘swallowed up film studios at Shepherd’s Bush, Wembley, Elstree, Highbury, Manchester, Merton Park, Hammersmith and Barnes’.3 It seemed as if the TV companies were taking over the entire British film industry.

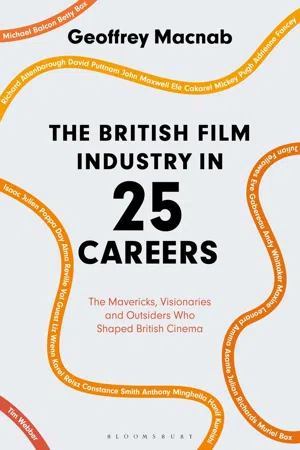

Michael Balcon. Photo: © Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images.

Ealing was regarded as part of the fabric of British cultural life. British cinema-goers were always predisposed to give new Ealing productions the benefit of the doubt. ‘At previews of its pictures, there is always an air of expectancy amounting to an attitude that many are apt to blame themselves and not the film if they do not like it. It is incredible, but when their efforts do not come up to scratch, everyone, even critics, seem genuinely sorry!’ wrote Jock MacGregor, the London correspondent for New York-based film exhibitor trade paper Showmen’s Trade Review.4 The trust for the films made at Ealing also extended to the company’s patrician boss. Balcon’s name on the credits was seen as a mark of integrity.

The sale of Ealing came a decade after Clement Attlee’s Labour Party had swept to power on a landslide in the 1945 election on its ‘Let Us Face the Future’ manifesto. To some pessimistic observers, Michael Balcon’s decision to sell Ealing marked the end of that period of optimism and idealism that had characterized the early years of the Attlee government, when sweeping changes to health, welfare and housing were introduced. The politicians were blamed for Ealing’s problems. As filmmaker Jill Craigie, the wife of prominent Labour politician Michael Foot, wrote in Tribune, ‘the blunt fact is that Ealing Studios have been taxed out of existence. Far more goes to the state in tax than to the producing of the films.’5

‘The last Labour Government was the only Government we have had that had some faint inkling – I suspect largely due to you – of the realities of the situation of the producer pure and simple; but in the long run the other branches of the industry succeeded in clouding the issue fairly effectively, the progress made still fell short of the progress desired,’ producer Anthony Havelock-Allan (best known for his work with David Lean) wrote to Balcon.6

On learning of Balcon’s decision to sell Ealing, trade union leader George Elvin, General Secretary of the Association of Cinematograph, Television and Allied Technicians (ACTT), had fired off a telegram begging Balcon to reconsider his decision:

URGE YOU ON BEHALF OF ACTT AND IN INTEREST OF BRITISH FILM FOR WHICH YOU HAVE DONE SO MUCH REOPEN NEGOTIATIONS WITH BBC TO OBTAIN RELEASE FROM CONTRACTS OF SALE STOP BRITISH FILM PRODUCTION CANNOT PROGRESS WITH DIMINISHING PRODUCTION FACILITIES STOP PLEASE DON’T STRANGLE THE MAN [Elvin’s characterization of the now mature British film industry] YOU HAVE BOTH MAGNIFICENTLY HELPED REAR FROM INFANCY STOP REQUEST YOU RECEIVE TRADE UNION DEPUTATION.7

Conservative elements within the film industry felt this telegram, which Elvin showed to the press, was in bad taste – a left-wing stunt. Balcon and Major Baker quickly came back to Elvin to tell him the arrangements they had made to dispose of Ealing were ‘binding and irrevocable’.

Two final films – comedy Who Done It (1956), directed by Ealing veteran Basil Dearden and starring the young comedian Benny Hill in his screen debut as an ice-rink sweeper, and Charles Frend’s crime thriller The Long Arm (1956), starring staunch British leading man Jack Hawkins – were to be completed at Ealing. Then, Balcon and his 400 staff vacated the premises, leaving it to its new owners.

In their letters and public pronouncements, Balcon and Baker repeated again and again that the team would soon be setting up shop elsewhere. They were already in discussions to lease space at the MGM Studios in Borehamwood. They mustered arguments intended to show that the deal with the BBC was a matter of common sense. It had always been a financial struggle to keep Ealing going. When Balcon took over at the studios in 1938, they had capital of £80,000 and debts of £300,000. Over the years, the debt had been paid off but Ealing’s finances had been badly hit when one of their principal backers, the former chairman Stephen Courtauld, a philanthropist whose wealth came from his family’s textile business, had withdrawn his backing from the studios in 1951 when he and his family moved abroad to live in Rhodesia.

By 1955, Balcon was in a continual struggle to keep Ealing going. He was borrowing money from the government-backed Film Finance Corporation and was relying on support from the Rank Organisation, which was itself retrenching. The studios, which had opened in 1931, were considered old fashioned; well suited for smaller films, they were no longer big enough to make the expensive movies that might be able to compete with the big Hollywood productions then being made to show up the majesty of cinema in a period when television was stealing away audiences.

Balcon wanted to believe that the famous Ealing spirit, its quiet professionalism and emphasis on teamwork, wasn’t anything to do with bricks and mortar. If the same technicians were making films in Borehamwood, that spirit could be preserved. Balcon hoped he and his colleagues could continue making films ‘in committee’.

‘In retrospect there is a good deal to be said for the methods of Michael Balcon, the Knight of the Round Table … is that Diana Dors? … and Joan Collins? Yes. They were rare interlopers, for Ealing’s world was largely peopled by strong, silent men,’ former Ealing publicity man Monja Danischewsky wrote of Balcon’s collective, masculine approach to the business of filmmaking.8

As it turned out, union leader Elvin was right and the shocked response from Fleet Street was justified. The moment Balcon took Ealing Studios away from its west London home, the magic surrounding its films began to dissipate. The ‘fine team spirit’9 which Balcon’s old colleagues all talked about simply couldn’t be replicated elsewhere.

There was a sense of ‘all my sad captains’ in the nostalgic and melancholic letters and telegrams Balcon’s most trusted workers and associates sent to him after the sale was announced. Message after message from actors, cinematographers and members of the public came to Balcon, all expressing their regret that the Ealing spirit was threatened with extinction. Actor Derek Bond, who had played Nicholas Nickleby and Captain Oates in Ealing films, spoke of his ‘deep affection for the studios and the folk who work her...