![]()

Chapter 1

Solid as Rock

“Concrete?” my friend said. “You’re going to write a book about what?”

I suppose the reaction shouldn’t have surprised me. Concrete has a bad rap in many quarters, particularly among people who pride themselves on being eco-friendly, nature loving, and sensitive to aesthetics. Many of my friends count themselves among them, and I suppose that most of the time I’d include myself on their team. Certainly my little inner-city garden with its billows of native plants in August suggests that.

But concrete is responsible, for good or ill, for the world we live in today, and not to appreciate it is to ignore both its menace and its beauty. Without it there would be no high-rises, no grand irrigation projects, no lettuce from California in the winter, no green golf courses in Arizona, a penury of hydroelectricity, more mud in some places, more solitude in others, and, very likely, little prospect of the disastrous climate change that is going to rain on our parade.

Don’t believe me? Look out the nearest window, then try to imagine what the view would look like without concrete. Say your view is a cityscape; you’ll have to mentally erase the apartment building across the street because the foundation is certainly made from concrete, and so might be the walls and the flooring. There’d be no sidewalks and perhaps no paved street. Underneath there’d likely be no sewer pipes, and unless the water pipes have been recently laid, none of them either. In fact, there might be no water coming your way at all, since in many places water comes from concrete storage dams that store water from rain and rivers.

Or perhaps you’re in a suburb or the country. Even here the view would be drastically changed without concrete since low-rise, single-family houses are built on concrete foundations, even if their walls and roofs are made from other materials.

Then suppose the day is ending and twilight is falling on this transformed landscape. Time to switch on the lights—but no, in many places there would be no electricity because it is generated by water impounded in concrete dams. Nor would coal- or gas-powered electricity generating plants be operating because their smokestacks are made of concrete. Nuclear power would also be non-existent since the guts of reactors have to be shielded by tons and tons of concrete.

So, in the semi-darkness you might decide to grab a snack to boost your spirits while you contemplate this fundamentally different world. Be prepared: the food available would be much less varied than what you’re used to. There’d be nothing from irrigated fields, nothing that had been transported long distances by truck, nothing that had been stored and transformed in concrete warehouses and plants.

And don’t even think of escaping this gloomy state of affairs by catching a sporting event or losing yourself in a monster show by a pop star: the stadiums and auditoriums they are held in are all made of concrete.

Convinced? Well, perhaps about concrete’s usefulness. If you want more about its beauty—and its menace—just wait a bit.

The wonders of concrete—and I don’t think the term is an exaggeration—became apparent to me during several years of researching and writing about urban spaces and urban life that culminated in my book Road Through Time: The Story of Humanity on the Move (University of Regina Press, 2017). Roads are about the most enduring creations we build, and where they go, goes change. Today, new paved roads are usually in part constructed of concrete, and as I travelled them, I began to think about what would happen if there were no concrete to build them. Then, as one thing leads to another, I began wondering what would happen if there were no concrete at all. That led me down a number of paths, to libraries, construction sites, dams, housing projects, cement plants, and modern monuments. At the end, I encountered the wall that our civilization appears to be headed for—disastrous climate change—and that concrete has helped construct as certainly as if it had been poured from jumbo concrete pumper trucks.

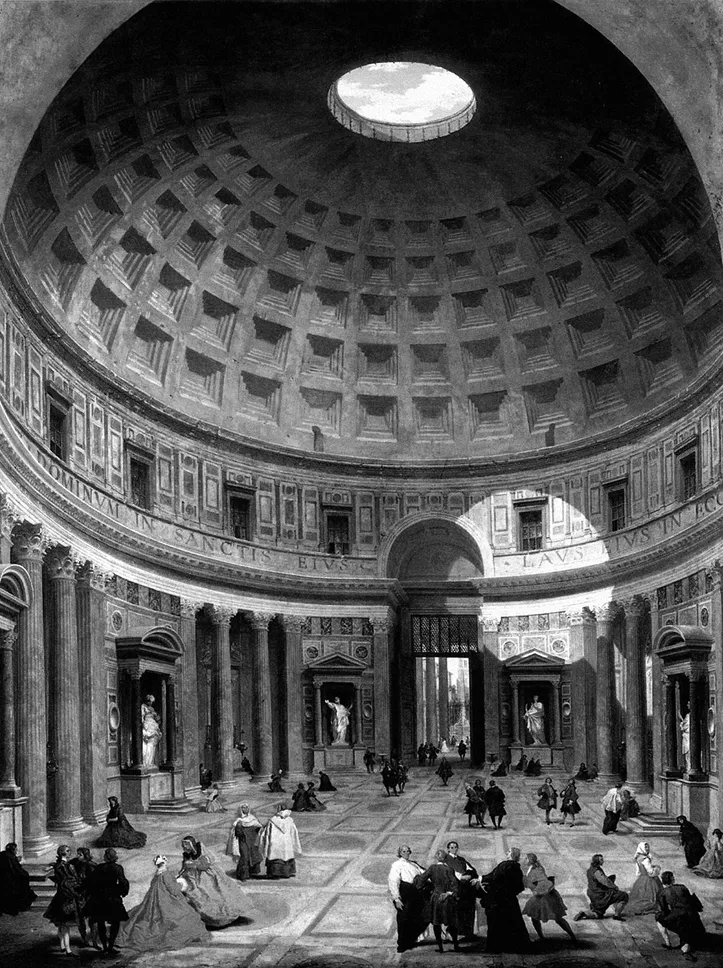

The first thing I realized was that concrete has its roots in deep time; in many respects it really is a “Rock of Ages.” Cement, the material that holds concrete together, is in large part made from rocks laid down hundreds of millions of years ago when the shells and carapaces of organisms settled in the bottom of seas. Concrete can also last for thousands of years. Some Roman concrete is in great shape today: the dome of the Pantheon built in Rome circa 125 CE is still the largest concrete dome that isn’t reinforced with steel. Just as impressive are the remains of a vast harbour installation constructed about 150 years before that off the coast of what is now Israel. While the docks and breakwaters are submerged today, the concrete is still strong, unlike that of many piers and wharfs constructed merely decades ago.

The second thing I learned as I tried to tease out both the history and chemistry of concrete is that what is considered concrete has changed over the centuries. Today, concrete is defined as the substance created by a judicious mix of a binder (usually a variation of Portland cement), sand and/or aggregate, perhaps a couple of additives, and water. The slurry produced can be poured into forms, where it hardens. Through a chemical reaction, the cementitious material binds the aggregate together by making a lattice-like web of molecules that hardens over time, sort of the way water forms ice crystals as it freezes. In concrete, after twenty-four hours or so, the transformed mixture will be hard enough in most instances that forms can be removed. However, it won’t usually reach its design strength for twenty-eight days and may continue to gain strength well after as it ages.

Figure 1.1: Rome’s Pantheon, built nearly 1,900 years ago, is still the largest unreinforced dome in the world. Painting by Giovanni Paolo Panini, ca. 1730. Public Domain.

Today, we don’t know how long it took for the concrete the Romans made to set, and we are only now unravelling some of its chemical mysteries. Sometimes they poured it, as when they made harbour installations, but most often it was made and used quite differently from the way it’s used today. Basically, it was mortar made from fired limestone, water, and ordinary sand that was frequently mixed with volcanic sand or ground-up bricks. It was then slathered onto or poured over rocks of various sizes; our word cement, which now refers to the substance that makes concrete stick together, comes from the Latin word for what we’d call rubble or aggregate: caementum.

Figure 1.2: Roman walls, like this one at Conímbriga in Portugal, were made with a concrete core and stone facing. Photo: Mary Soderstrom.

But the Romans were far from the first people to discover one of the key elements in their magic mix, because people all over the world again and again stumbled on the amazing properties of fired limestone, also called quicklime. Each time must have been literally an explosive surprise because a sudden, intense reaction that sets the water and the rock raging is what happens when you add superheated limestone to water. Some historians suggest that a lightning strike that burned limestone set the scene for the discovery. Or perhaps the process was encountered when early humans heated rocks to make it easier to work flint or obsidian in toolmaking: there’s evidence that fire was used to crack rocks as far back as 20,000 BCE.

Or perhaps—and this seems more likely to me, given it’s clear that lime mortar was made well before techniques for making pottery were developed—the discovery is related to the way many Indigenous Peoples have cooked food. You may have done it yourself on a Scout excursion or at summer camp. You begin by filling a container—a pouch made of hide, perhaps, or a basket of tightly woven grasses, or a vessel made of bark stripped from a tree—with water, grains, and perhaps meat. Then you heat stones on a fire until they are very hot. When y...