![]()

CHAPTER 1

Isn’t Change Management Simply Good Communication?

One thing is certain… change is all around us and is always happening because the world is constantly changing (Dawson 1996; Fullen 2001; Mabey and Mayon-White 1993). The big motivator for change is to make things better in one way or another (whether this is because of a crisis, high performance, reconciliation, market fluctuations, etc.). The specific reasons vary, but the overarching aim for organizations is predominately the same – to make things better (whether this is to increase profit, market share, differentiation, etc.). The desire for us as a society at the moment to make things better is enormous – all you have to do is visit the very large self-help section of any bookshop (online or otherwise). We are constantly looking to others to show us how we can be better than we are now – for example, by losing weight, or controlling stress or anger or… you can fill in the blank with a range of self-improvements. Our desire for improvement extends to our professional lives and the organizations in which we work. In these instances, the overarching driver for change or improvement is leadership. Statistics have proven that the most common reason an individual would leave or remain within an organization is due to the relationship, or lack thereof, with their line manager.

THE COMPONENTS OF CHANGE MANAGEMENT

So, how does leadership impact change? To start, let’s discuss what change is and how it happens. At its most basic, change is what happens when you move from one state to another state (Lewin 1935). It is not a perfect process and cannot always be planned. Even when change is managed, it does not always go according to plan. A range of factors such as circumstances, finances and people can impact how change occurs. The way people react to change has a great impact, not only on the approach or levels of resistance to change, but also on whether the change is actually applied and happens. Taking into consideration that some people cope with unpredictability better than others, it is critical for managers to remember, first and foremost, the people they are leading and managing. After all, they are the people who will actually make the change happen, one way or another.

The way change happens is very dependent on the behaviour of people. As a result, there will be a strong focus on the behaviour of leadership in this book, as it is through behaviour we can understand what we should or should not do as leaders in change.

When it comes to organizational change or change within an organization, there is a dependency on the skill and ability of leaders to flex their leadership styles. For example, Sally was a senior leader in a regional office and her natural leadership style was coaching. When she first started out in the role, she wanted to change the culture of how her team contributed to and resolved business challenges – she wanted them to take more responsibility and collaborate as a team. In the beginning, her coaching leadership style was not enabling the change she wanted to make. This was due to the team not being used to working in this way, and they were sceptical of her motives and approach. The previous leader used a telling or commanding approach, so they were used to someone telling them what to do, not asking them what they thought they should do. Sally realized she needed to flex her typical style to help the team make the transition and demonstrate that she genuinely wanted their thoughts and ideas. It took some time, and took longer than Sally originally anticipated for the change to happen, but she eventually got the impact and results she was aiming for with the culture change.

Organizational leaders need to recognize that change is complex (Fullen 2001), imperfect and dependent on human behaviours. Managing change also requires flexibility in leadership styles. Many managers believe that if they tell people what the change is, then people will come and do/use it. However, experience has demonstrated on multiple occasions that this is not the case. People need to be brought along on the journey of change; they need to understand not only what the change is, but how different the new state is in comparison to the current state, and how that specifically has an impact on them – not to mention why they should cooperate with the change in the first place.

Individual behaviour has a great impact on the outputs of change, and it only really happens when people are willing to make the change. To continue the above example, if Sally carried on applying her typical leadership style of coaching, rather than flexing her approach and using different styles to help her team through the change, then she would not have achieved the results she was aiming for. This is because she needed to help the people in her team to change their behaviour and want to make the change. She needed to be confident and reassure her team that there would not be negative repercussions – her ask of the team was genuine and wanted. The role of the team in understanding and dealing with the change was critical to managing the shift towards a better culture.

Peters (1991) says we should not discuss change but organizational revolution. Argyris (1985) talks about change management as flawed advice. Kotter (1995) puts forward a top-down change transformation process; and Beer, Eisenstat and Spector (1990) discuss a bottom-up process. With all these different ideas on managing change, it is no wonder the subject is confusing.

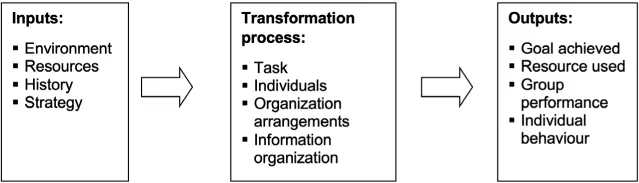

So, perhaps the best way to start is to take into consideration the different approaches to managing change. If the view that organizations are complex open social systems is accepted, then those systems will impact the results of change within organizations (Katz and Kahn 1966). As we have already mentioned, it is well known that change only really happens within an organization if the individuals are willing to make the change. The Congruence Model of Organizational Behaviour (Nadler and Tushman 1979) defines a set of four inputs that lead to a transformation process within the organizational components, which then lead to the outputs of change highlighted by organizational performance (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Congruence Model of Organizational Behaviour

Source: Nadler and Tushman 1979.

According to this model, essentially an organization takes inputs and then generates outputs, so it is within the transformation process where change occurs. It is during this phase that leadership behaviours and skills are critical to the outputs generated. ‘To change anything requires the cooperation and consent of the groups and individuals who make up an organization, for it is only through their behaviour that an organization can change’ (Burnes 2004, p. 267).

The question is, how can leadership and change skills be linked together to give managers a roadmap to follow when implementing change?

Utilizing the model above, there are some key questions that should be asked at the start, when working with, managing or dealing with a change:

1. Who needs to be involved?

2. What tactics or methods will best deliver the change?

3. How ready is the organization and its people for change?

In my experience, the first two questions are typically asked within an organization, which is why stakeholder management and communication are two key elements within any change management job description. However, the third question – how ready is the organization and its people for the change? – is one that is not asked very often and can have huge impacts on the success of the change. It may seem obvious, but it is a common mistake within an organization for a person to decide a change needs to happen and pull together a project team without asking whether the organization ready for it. For example, do they have all the right processes, procedures, policies, tools to enable the change? If the organization is set up for the change, do the employees have everything they need? How ready are the people? – do they want to change? What is in it for them to change? Why would they want to make the change? Many times, the ‘What’s in it for me?’ (WIFM) question is posed at a much later state in the change process, when actually it needs to be factored in at the very start of the change, as this will drive the vision, communication, motivation and hence the people through the change.

All of these questions should be used and asked by every leader or manager of change. This will help greatly when it comes to applying the ABChange model and driving the change down a path of success.

CHANGE MANAGEMENT VERSUS GOOD COMMUNICATION

Rightly or wrongly, experience has shown that many people believe change management is the same as good communication. In reality, they are very different disciplines. Communication allows people to know what is going on, when and where; in other words, it shares information. However, change, as discussed earlier, is about moving something from one state to another. Although communicating and communications are key tools within change management and help with enabling change, the sum of communications is not change. An organization can send out hundreds of communications about a project, but that does not equate to change, successful or otherwise. For example, an infrastructure organization was embarking on a digital change – they wanted (like many other companies) to be digital by default. When they started the change, they sent out multiple communications announcing the change and the aim of the organization, but one year later, people still did not know what the change was all about, much less what they needed to do differently. Something more needed to happen to actually enable change to happen.

It stands to reason the business of managing change has a number of key steps and the articulation of these steps varies slightly depending on who is setting them. Stebbins (2017) argues that the quality of communication is the ‘single most important contributor to managing resistance to change’. So, what makes a good communication and how does that contribute to successful change management?

There can be times during a project when it seems like the ‘right hand does not know what the left hand is doing’. This is a clear sign that there is a gap in communication. When there is a need to move people from one state to another, clear and concise communication is critical to counteract resistance, as well as rumours, misperceptions and misconceptions.

Communication is a science and a fine art. The science is built all around the purpose: to give people information on what, where, why, how and when. However the fine art to communicating involves the elements beyond the logistics. The timing, tone, methods and channels also all play a crucial role in communication. If the communication for a change is too early or too late, then it will miss the mark and not have the desired impact, begging the question, why do it in the first place? It is the same for the other ‘art’ elements.

On a particular project with a financial services organization, there was a great deal of frustration, confusion and even anger within the project team. The reason for this predominately came down to poor communication. To combat this, communication needs to be clear, concise, authentic and genuine in what and how it comes across (Juneja 2018), which is how the situation was rectified. It was agreed what communication would happen, when and by whom, and if this was not completed for some reason, then the reasons for this failure were communicated. This tactic reduced the level of frustration and confusion within the project.

Communication also needs to be in an accepted form that fits the culture of the organization. For example, if an organization does not promote using email to communicate with staff, then that method would not be the best way for people to receive information. (More on culture is discussed in Chapter 6.) Several different types of medium should be given serious consideration to ensure an appeal to a wide audience (video, posters, emails, newsletters, etc.). Knowing how staff receive other organizational information is a good indicator of the best methods for communicating change programmes as well. The content itself needs to align with the company’s cultural norms – essentially this makes it easier for people to receive, accept and process the information.

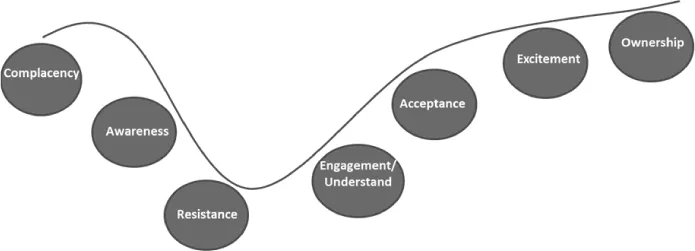

In order to influence stakeholders there needs to be a series of steps that enable people to reach different processing levels in change. The Kübler-Ross model (1969) defines these steps clearly.

From a communication perspective, it is about moving people through the change curve from awareness to understanding to acceptance and finally commitment. The space between understanding and acceptance is at the dip in the change curve, and there is a risk that people go around and around in the dip – what I call the ‘washing-machine cycle’. To prevent this from happening, leaders and managers within an organization need to clearly build and express their skills in leadership, change and influencing by using good communication with their teams. The process of this should be integrated into the change and communication plan, in order to have a positive impact and help bring people along the journey of change. This will also help manage expectations and ensure people are given the right information, in the right way, at the right time. When change and communication are not properly planned, then the consequences can lead to high levels of resistance and potential failure of the change itself.

Kübler-Ro...