![]()

ORIGINS OF A CATASTROPHE

High in the Bavarian Alps in August 1939, a group of Germans looked toward the heavens and beheld a spectacular display of the aurora borealis that covered the entire northern sky in shimmering blood-red light. One of the spectators noted in his memoirs that “the last act of Götterdämmerung could not have been more effectively staged.” Another spectator, a pensive Adolf Hitler, commented to an adjutant: “Looks like a great deal of blood. This time we won’t bring it off without violence.”1 Hitler, the author and perpetrator of the coming catastrophe, knew full well of what he spoke, for he was about to unleash another terrible conflict, first on Europe and eventually on the world. How had Europe again come to the brink of hostilities barely a quarter century after the start of World War I—a clash of nations that had tumbled empires and destroyed a generation? It was indeed a sad tale of fumbled hopes and dark dreams.

The war that Hitler was soon to begin brought a new dimension to the cold, dark world of power and states, for it combined the technologies of the twentieth century with the ferocious ideological commitment of the French Revolution. The wreckage of 1918 had certainly suggested the possibilities. But the democracies chose to forget the harsh lessons of that war in the comfortable belief that it all had been a terrible mistake; that a proper dose of reasonableness—the League of Nations along with pacifist sentiments—would keep the world safe for democracy. Instead, the peace of 1919 collapsed because the Allies, whose interest demanded that they defend it, did not, while the defeated powers had no intention of abiding the results. The United States, weary of European troubles, withdrew into isolationism, and Britain followed to the extent geography allowed. Only France, vulnerable in its continental position, attempted to maintain the peace.

From the first, the Germans dreamed of overturning the Treaty of Versailles, which had codified their humiliation. The Italians and then the Japanese, both disappointed by their share in the spoils, displayed little interest in supporting the post–World War I order, while the revolutionaries in Russia focused on winning their own civil war and then on establishing socialism in the new nation. The ingredients for the failure of peace were present from the moment the armistice was signed; the inconclusive end to World War I, with the German Army still on foreign territory, made another European war inevitable. The appointment of Hitler as chancellor of Germany in January 1933 and the ensuing Nazi revolution ensured war on a major scale, involving nothing less than a bid for German hegemony over the entire continent.

Adolf Hitler was crucial to the rise of National Socialism. Beyond his political shrewdness, he possessed beliefs that fit well with German perceptions and prejudices. Ideology was central to his message. Above all, he rejected the optimistic values of the nineteenth century, in favor of a worldview that rested on race and race alone. On one side were the Aryans, best typified by the Germans, who had created the great civilizations of the past; on the other side were the Jews, degenerate corrupters of the social order, who had poisoned societies throughout history. In Hitler’s view, Marxism, socialism, and capitalism were all ills that flowed from the effort of Jews to destroy civilization from within. Hitler believed that he had uncovered in his race theories the fundamental principles on which human development and human history turned. He had no more evidence for his system than Marx and Engels and their successors, Lenin and Stalin, had for their illusions, but ideologies, like religions, do not rest on facts or reality; they rest on beliefs, hopes, and fears.

The “biological world evolution” to which the Nazis aspired married other nasty quirks to anti-Semitism. According to Hitler, a lack of “living space” (Lebensraum) thwarted Germany’s potential; great nations require territory on which to grow. Consequently, Germany would have to either seize the economic and agricultural base required to expand or else wane into a third-rate power. Russia’s open spaces beckoned; in Hitler’s view, they were inhabited by worthless subhumans, whom the Germans could enslave. German conquest would begin with the elimination of the educated elites in Slavic lands. The remaining population would then be killed, expelled, or enslaved as Helots. On these conceptions rested everything that Hitler and his Germans, military and civilians, would do in the coming five and a half years of war. The success or failure of Hitler’s program would depend on the ruthlessness with which the leadership acted and how effectively Hitler fused his fierce ideology to a civilian administrative structure and military machine capable of executing his wishes. In both endeavors he was all too successful.

It has become popular among some historians to suggest that the “internal” contradictions of Nazism would eventually have resulted in the regime’s collapse. Such views are questionable. Admittedly, internal dynamics and economic strains pushed the Third Reich toward war, but saying that is only to underline that war and the destruction of other nations were part and parcel of Nazi ideology. Had Hitler won, his regime had already proved it could find and motivate the people required to keep the system working.

Most leaders and observers on the Left missed the demonic nature of the Nazi threat. Leon Trotsky contemptuously remarked that the Fascist movement was human dust, while Joseph Stalin argued that Fascism represented capitalism’s last stage. The Communists busily attacked the Social Democrats as “Social Fascists” in the early 1930s, thereby shattering the unity of the Left, especially in Germany. Stalin’s German stooges were as much the enemies of the Republic as the Nazis, just less skilled.

There were, of course, many who prepared the way for Nazism. A massive disinformation campaign by the Weimar Republic’s bureaucracy persuaded most Germans that the Reich had not been responsible for the last war and that in November 1918 the army had stood undefeated in the field until Jews and Communists stabbed it in the back. A national mood of selfpity and self-indulgence fueled the Nazi Party’s attractiveness.

Initial Moves

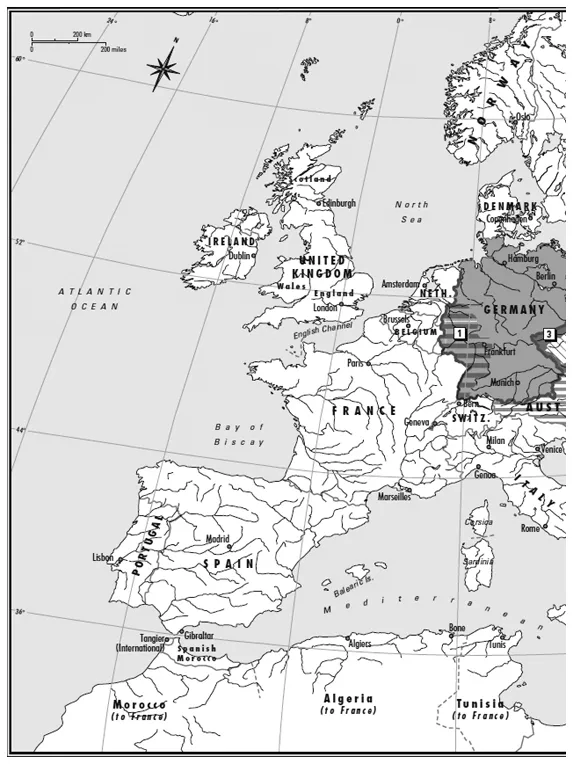

In strategic terms Germany had won the Great War. Its industrial base remained intact; it lost little territory of value; it now fronted on one major power (a debilitated France) rather than three (France, Austria-Hungary, and Russia). Its industrial strength, its geographic position, and the size of its population gave it the greatest economic potential in Europe, while the small states of Eastern Europe and the Balkans were all open to German political and economic domination.

However, these advantages remained opaque to a nation that felt humiliated by defeat in 1918. For the Nazis, Germany’s postwar economic situation offered a considerable stumbling block to regaining the Reich’s great position of power. The Versailles Treaty’s restrictions on arms manufacturing left even the Krupp industrial empire with little capacity for military production. In 1933 the aircraft industry, for example, possessed only 4,000 workers divided among a group of bankrupt manufacturers known more for their quarrels than for the quality of their products. The only raw material the Reich possessed in abundance was coal; oil, rubber, iron, nickel, copper, and aluminum were in short supply or nonexistent. Consequently, Germany had to import these materials, and in the 1930s imports required foreign exchange, which Germany did not have. As with all armament efforts, German production did not immediately rise to meet expectations.

Hitler did warn the German generals in February 1933 that France, if it possessed true leaders, would recognize the German threat and immediately mobilize its forces. If that did not happen, Germany would destroy the European system, not make minor changes to the Versailles Treaty. Hitler’s intuition was right; France did not have leaders willing to make a stand. In the years of preparation for war, Hitler managed German diplomacy with consummate skill despite the Third Reich’s military weaknesses. In 1933 Germany withdrew from the League of Nations and then in the following year signed a nonaggression pact with Poland, removing the Poles as a threat in the east. These diplomatic moves thoroughly confused Hitler’s opponents. With few exceptions, Europeans hoped that the Führer was reasonable and that they could accommodate the new Nazi regime.

In Britain, most were deceived. Only Churchill warned: “‘I marvel at the complacency of Ministers in the face of the frightful experiences through which we have so newly passed. I look with wonder upon our thoughtless crowds disporting themselves in the summer sunshine,’ and all the while, across the North Sea, ‘a terrible process is astir. Germany is arming.’”2 It was indeed a lonely fight that Churchill waged. Well might John Milton’s words in Paradise Lost about the angel Abdiel have been applied to Churchill: “Among the faithless, faithful only hee; Among innumerable false, unmov’d / Unshak’n, unseduc’d, unterrifi’d.”3

More in tune with the European mood was the London Times’s response to Hitler’s purge of the SA (Sturmabteilung), the Nazi Party’s paramilitary arm, when firing squads executed several hundred Nazi storm troopers: “Herr Hitler, whatever one may think of his methods, is genuinely trying to transform revolutionary fervor into moderate and constructive efforts and to impose a higher standard on National Socialist officials.”4

The political Left warned of the danger of Fascism, but regarded the threat as internal rather than external. In Britain, the Labour Party urged aid for the Spanish Republic, which was fighting for its life, but voted against every defense appropriation through 1939. In France, the Popular Front government of Léon Blum denounced Charles de Gaulle’s proposals for an armored force as a gambit to create an army of aggression. If Germany attacked, Blum argued, no armored force was required; the working class would rise as one man to defend the Republic. His government undermined France’s defense industry with social legislation and kept the lid on defense spending so that even Italy outspent France in the 1935–1938 period.

Soviet foreign policy was equally irrelevant; Stalin encouraged formation of “popular-front” movements against Fascism, but his policy aimed more at encouraging a war among the capitalists than at stopping Hitler. A savage purge in 1937 which decimated the Soviet military was further evidence of Stalin’s belief that war with Nazi Germany was unlikely.

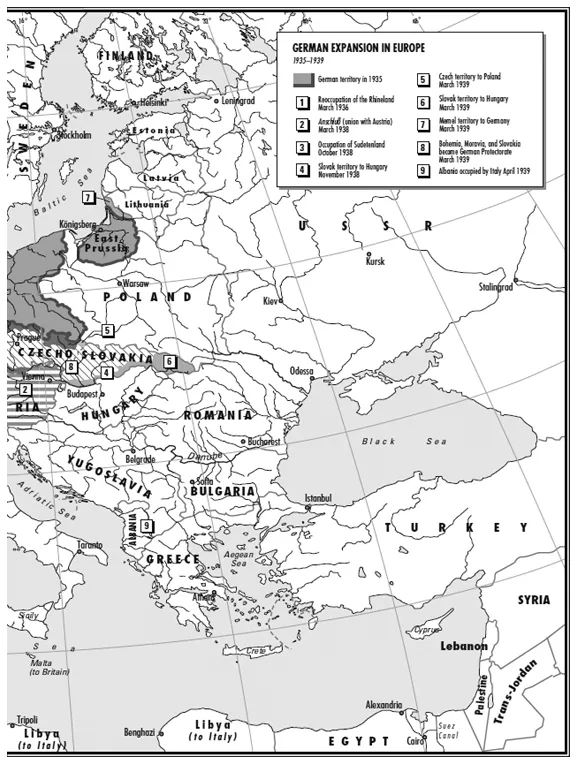

In 1935 Benito Mussolini invaded Abyssinia and added that country to Italy’s colonial domain. Using the Italian war in Africa as cover, Hitler remilitarized the Rhineland in March 1936, thus flouting one of the most important provisions of the Versailles Treaty. A political crisis in France that led to the fall of the government rendered French protests against the Germans meaningless. And all the British could manage to mobilize was vague talk about the Germans moving into their own backyard.

In July 1936 the civil war broke out in Spain, and that conflict furthered Hitler’s interests by distracting Europeans from the German threat. While Hitler provided some help to Francisco Franco, the rebellion’s leader, German aid remained limited. In December 1936 Hitler flatly refused Spanish requests for three divisions and remarked that it was in the Reich’s interest that Europe’s attention remain focused on Spain. The Spanish Civil War dragged on, living up to Hitler’s expectations. Franco deliberately drew out the conflict to kill the maximum number of his loyalist opponents.

In addition to the suffering inflicted on the Spanish people, the war exercised a baneful influence on Germany’s potential opponents, particularly France, which was almost torn apart by the war’s political fallout. The British government moralized, but did little to prevent the rush of arms and men to both sides. Stalin provided military equipment but remained more interested in exporting the NKVD (Soviet Secret Police) and Soviet paranoia than in defeating Fascism. Aside from Spain, Italy lost the most, however. By providing “volunteers” and arms to Franco, Mussolini retarded the modernization of his own military. All that Italy got in return was promises which, in the harsh world of the 1940s, Franco failed to keep.

After his Rhineland success, Hitler’s planning proceeded for two years without a major crisis. The performance of German Army units in autumn 1937 maneuvers, however, indicated that the day of reckoning was not far off. Observers such as Mussolini and Britain’s General Edmund Iron side left East Prussia impressed with the German Army’s efficiency. But the Germans were having serious economic difficulties. There was simply not enough foreign exchange to pay for the imports of raw materials required to fulfill the massive rearmament programs. From September 1937 through February 1939, these shortages prevented German industry from completing over 40 percent of orders on schedule.

In November 1937 Hitler met with his chief advisers to discuss these strategic and economic problems. The minutes of the meeting emphasize the Führer’s belief that the Reich must soon embark on an aggressive foreign policy. His predictions about possible future wars were far-fetched, but the immediate targets, Austria and Czechoslovakia, were clear enough. However, Hitler ran into opposition from General Werner von Fritsch (the army’s commander-in-chief), Field Marshal Werner von Blomberg (the war minister), and Konstantin von Neurath (the foreign minister). All three agreed that Germany was not ready for war and that a premature move could lead to disaster. Discussions were inconclusive, although within the month, Blomberg ordered contingency plans recast.

The hesitation of his senior advisers upset Hitler deeply. At the end of January 1938 he made his move; Blomberg’s misalliance with a woman who had “a past” provided the excuse. The generals demanded Blomberg’s removal, and Hitler gladly accommodated them. Then, using trumped-up charges of homosexuality, he turned on Fritsch and fired him as well. To complete the purge, Hitler replaced Neurath with his protégé Joachim von Ribbentrop, at the same time that he retired or transferred a number of other senior officers. Hitler then assumed control at the War Ministry himself and appointed General Wilhelm Keitel—remarkable even among German generals for obsequiousness—as his chief military assistant.

The purge presaged a major turn in policy. Hitler now controlled both the military and the diplomatic bureaucracies. However, the triumph was short-lived. The case against Fritsch dissolved due to the incompetence of the SS (Schutzstaffel, the Nazi Party’s security and secret police). By March 1938, shortly before the opening of Fritsch’s court-martial, Hitler and the officer corps appeared headed for collision.

The confrontation never took place, because at the same time the SS case against Fritsch was unraveling, Hitler was pursuing his dream of Anschluß—union with Austria. At a mid-February meeting with Austrian Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg, Hitler demanded concessions that undercut Austrian independence. In response, Schuschnigg declared a plebiscite to determine whether Austrians were for a “free, independent, and Christian Austria.” Enraged, the Führer ordered mobilization against Austria; at the same time, the Nazis placed great diplomatic pressure on Vienna to capitulate. Austria collapsed, its destruction abetted by its indigenous Nazi movement and Europe’s indifference. Schuschnigg surrendered to Hitler’s demands that he resign and allow the Nazi Arthur Seyss-Inquart to assume the position of chancellor. A hastily mobilized German Army then marched into Austria. Ecstatic crowds welcomed their new masters, while others desperately sought to escape. Hitler, his emotions thoroughly aroused by the enthusiasm of his Austrian fellow countrymen, almost immediately announced the union of Austria and Germany. For the next seven years Austria disappeared from Europe’s maps, more willingly than those who were to follow.

The Anschluß ended the furor over Fritsch’s removal. The German Army had accomplished its first major operation since World War I with no substantial problems. Nevertheless, military weaknesses did show up: careless march discipline, mechanical and logistical problems with the armored forces, and inadequate mobilization measures. As in the past, the army readily set out to learn from its experiences.

Although the Anschluß failed to solve Germany’s long-range strategic problems as a resource-poor nation, it did bring short-term help. The Austrians possessed considerable foreign currency holdings which immediately aided the Reich’s rearmament programs. One estimate at the time calculated that financial gains from the Anschluß underwrote the costs of rearmament for the rest of 1938, while by 1939 Austrian factories were turning out Bf 109 fighters and contributing considerably to the Reich’s production of high-grade steel. The Austrian campaign netted military and strategic gains as well. Germany now surrounded Czechoslovakia on three sides and possessed direct frontiers with Hungary, Yugoslavia, and Italy. The Austrian Army, though of mixed quality, added five divisions to the German Army (two mountain, two infantry, and one motorized).

The self-serving memoirs of German generals such as Heinz Guderian describe the atmosphere in which “their Austrian comrades” joined the new “Greater German” Army as being happy and light. In fact, the heavy hand of National Socialism fell on anti-Nazi Austrians, military and civilian alike. Thirty senior Austrian officers were incarcerated in Dachau, while the Gestapo (Ge[heime] Sta[ats]po[lizei...