- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This classic paperback is available once again—and exclusively—from Harvard University Press.This book is the story of the life of Nisa, a member of the !Kung tribe of hunter-gatherers from southern Africa's Kalahari desert. Told in her own words—earthy, emotional, vivid—to Marjorie Shostak, a Harvard anthropologist who succeeded, with Nisa's collaboration, in breaking through the immense barriers of language and culture, the story is a fascinating view of a remarkable woman.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Nisa by Marjorie Shostak in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

Harvard University PressYear

2000Print ISBN

9780674004320, 9780674624856eBook ISBN

9780674256712

1

Earliest Memories

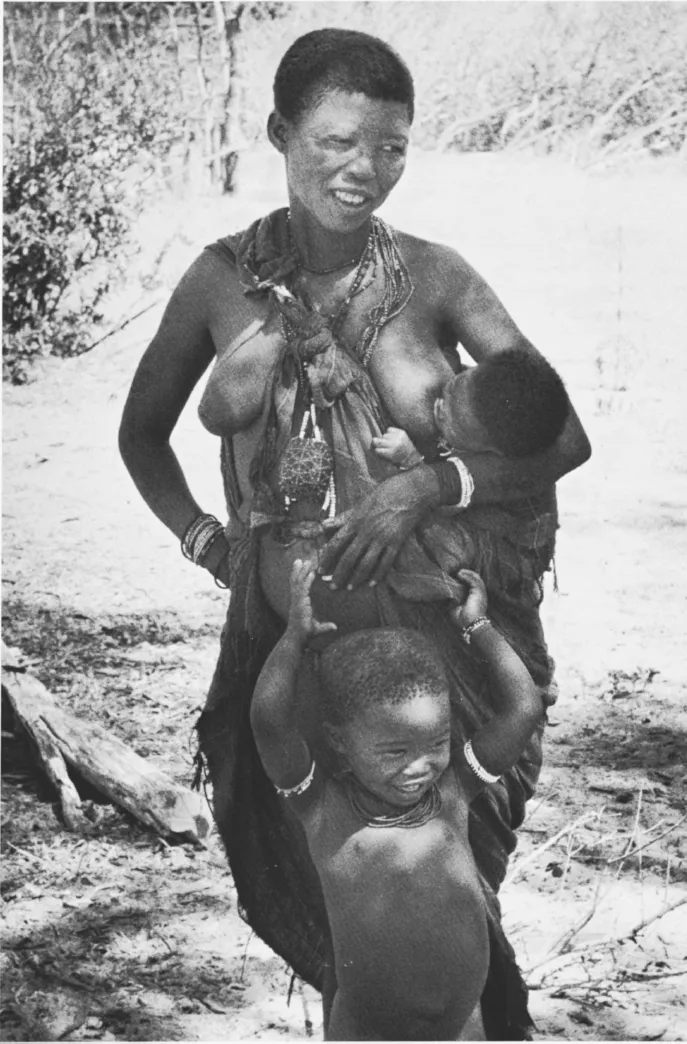

!Kung children spend their first few years in almost constant close contact with their mothers. The !Kung infant has continual access to the mother’s breast, day and night, usually for at least three years, and nurses on demand several times an hour. The child sleeps beside the mother at night, and during the day is carried in a sling, skin-to-skin on the mother’s hip, wherever the mother goes, at work or at play. (This position is an ideal height for older children, who love to entertain babies.) When the child is not in the sling, the mother may be amusing her—bouncing, singing, or talking. If they are physically separated, it is usually for short periods when the father, siblings, cousins, grandparents, aunts, uncles, or friends of the family are playing with the baby while the mother sits close by. Separation from the mother becomes more frequent after the middle of the second year, but even then it is initiated almost exclusively by the child, who is steadily drawn into the groups of children playing around the village. Still, the mother is usually available whenever needed.

!Kung fathers—indulgent, affectionate, and devoted—also form very intense mutual attachments with their children. Nevertheless, men spend only a small fraction of the time that women do in the company of children, especially infants, and avoid many of the less pleasant tasks of child care, such as toileting, cleaning and bathing, and nose wiping. They are also inclined to hand crying or fretful babies back to the mothers for consolation. Fathers, like mothers, are not viewed as figures of awesome authority, and their relationships with their children are intimate, nurturant, and physically close. Sharing the same living and sleeping space, children have easy access to both parents when they are around. As children—especially boys—get older, fathers spend even more time with them.

Assuming no serious illness, the first real break from the infant’s idyll of comfort and security comes with weaning, which typically begins when the child is around three years of age and the mother is pregnant again. Most !Kung believe that it is dangerous for a child to continue to nurse once the mother is pregnant with her next child. They say the milk in the woman’s breasts belongs to the fetus; harm could befall either the unborn child or its sibling if the latter were to continue to nurse. It is considered essential to wean quickly, but weaning meets the child’s strong resistance and may in fact take a number of months to accomplish. The usual procedure is to apply a paste made from a bitter root (or, more recently, tobacco resin) to the nipple, in the hope that the unpleasant taste will deter the child from sucking. Psychological pressure is also employed, as was clear from one woman’s memories of being weaned: “People told me that if I nursed, my younger sibling would bite me and hit me after she was born. They said that, of course, just to get me to stop nursing.”

If a child has recently been weaned and the mother miscarries, or if the new infant is stillborn or dies soon after birth, the older child may be allowed to nurse again. But this situation is considered far from ideal. One woman whose baby died and whose young son then resumed nursing was worried because her son had become ill. Other people in the village interpreted his illness as being caused by his mother’s milk, which had been meant for his dead sibling. In this time of stress the boy clung to his mother and to the security of her breasts with an intensity that was difficult for her to rebuff. Although she believed she should refuse him the breast, she too was suffering and could not bring herself to do it. A few weeks later she did find the strength, and soon after that her son got better.

Because of the physical and emotional comfort nursing affords, most children do not give it up easily. Also, with no domesticated animals to provide substitute sources of milk, the only alternative to nursing is to eat increased amounts of bush foods, but these do not compare to the appeal of mother’s milk. Children, therefore, are likely to be miserable during this period and often express their displeasure quite dramatically. Tantrums are typical, and general psychological distress is usually obvious. One man remembered, “I wanted to nurse after my younger brother was born, but my mother refused. I cried and my grandmother took me to another village so I would forget about nursing. But I thought about it anyway, and asked why she wouldn’t take me back to my mother so I could nurse. I was in great pain.”

The last-born child of a mother in her late thirties or early forties is spared the pain of abrupt weaning. If the mother does not get pregnant again, a child may nurse until the age of five or older, stopping only when social pressure such as mild ridicule from other children makes it difficult to continue.

When the new baby is born the older child also has to give up the coveted sleeping place immediately beside the mother. Although she may sleep between her parents for a while, an older child is eventually expected to sleep on the far side of her younger sibling. No surprise, then, that resentments and anger are frequently expressed toward the parents and sometimes even toward the new infant. This was clearly the case of a four-year-old who kept asking to hold her newborn brother. The mother finally took the baby from her sling and placed him gently in his sister’s arms. The girl sat and rocked the baby, singing to him and praising him, while her mother stood nearby. The next moment, however, hearing the shouts of other children playing, the girl suddenly stood up and dropped her tiny brother in the sand. Without a glance, she ran off, followed by her brother’s cries and her mother’s admonishments.

Within a year of being weaned from the breast the child is “weaned” from the sling as well. !Kung children love to be carried. They love the contact with their mothers, and they love not having to walk under the pressure of keeping up. As their mothers begin to suggest and then to insist that they walk along beside them, temper tantrums once again erupt: children refuse to walk, demand to be carried, and will not agree to be left behind in the village while their mothers gather for the day. Other people often make this adjustment easier by offering to carry the child, and on long walks a father will usually carry the child on his shoulder. By the age of six or seven, however, a child is expected to walk on her own and is no longer carried, even for short distances.

!Kung parents are concerned that these events not hit their children too hard, but coming as they do one after the other, these times are difficult at best. The father may try to spend more time with the child, or the child may stay with a devoted grandparent or aunt (who will be sure to spoil her) in a nearby village for a while. But parents are aware that the tremendous outpouring of love given each child in the first few years of life produces children who are typically secure and capable of handling this period of emotional stress. The extremely close relationship with their mothers seems to give children strength: the child has the mother’s almost exclusive attention for an average of forty-four months, thirty-six of these with unlimited access to the food and comfort afforded by nursing. Also, the child of three or four is no longer as needy of the mother’s attention as she had been. The boisterous play of other children ultimately becomes more appealing than continuing the conflict with the mother. Within a few months after the birth of their siblings, many children can be seen playing exuberantly most of the day and only occasionally behaving angrily with their families. Before long even these difficulties are largely overcome as the child starts enjoying the role of older sibling. Because children are between three and five years old when these events occur, many adults remember, if not the actual details, at least the feelings that accompanied weaning, both from the breast and from the sling. Some adults, looking back, see these events as having had a formative influence on their lives.

The !Kung economy is based on sharing, and children are encouraged to share things from their infancy. Among the first words a child learns are na (“give it to me”) and ihn (“take this”). But sharing is hard for children to learn, especially when they are expected to share with someone they resent or dislike. And giving or withholding food or possessions may be a powerful way to express anger, jealousy, and resentment, as well as love.

It is also hard to learn not simply to take what you want, when you want it. !Kung children rarely go hungry; even in the occasional times when food is scarce, they get preferential treatment. Food is sometimes withheld as a form of punishment for wasting or destroying it, but such punishment is always shortlived. Nevertheless, many adults recall “stealing” food as children. These episodes reflect the general !Kung anxiety about their food supply, as well as the pleasure they take in food—both emotions already present in childhood.

!Kung parents are tolerant toward children’s angry outbursts. Most youthful transgressions are explained by remarks like “Children have no sense” or “Their intelligence hasn’t come to them yet.” Behavior is judged, commented on, and occasionally criticized, and scoldings are not uncommon, but parents basically believe children to be utterly irresponsible. There is no doubt in the parents’ minds that as children grow up they will learn to act with sense, with or without deliberate training, simply as a result of maturation, social pressure and the desire to conform to group values. Since most !Kung adults are cooperative, generous, and hardworking and seem to be no more self-centered than any other people, this theory is evidently right, at least for them.

Although the !Kung say that children need to be disciplined, their efforts to do so are minimal. Adult attitudes toward discipline are not always clearly understood by a child, however—especially an older child, who may feel stronger pressure to conform. One young girl was convinced that a woman’s lack of response to the verbal assault of her young son was just as “senseless” as the boy’s behavior: “His mother didn’t do anything to him. She didn’t even yell at him. That’s how adults are—without sense. When a child insults them, they just sit there and laugh.”

Still, these early years are often remembered as times of intense conflict between parents and children. Beating and threats of beating are almost universal in the childhood memories of !Kung adults; yet observational research has shown that !Kung parents are highly indulgent with children of all ages, and physical punishment is almost never witnessed. It is probable that rare instances of physical punishment become exaggerated and vivid in the child’s memory. So, too, the much more common threats of beatings may be translated, in retrospect, into actual incidents. Whatever the reality, such memories dramatize the very real tensions that exist in !Kung families as in any others.

Grandparents (and often other relatives) are remembered much more favorably. Alternate generations are recognized as having a special relationship, especially when the child is the grandparent’s “namesake.” Personal and intimate topics not discussed with parents are taken up freely with grandparents, and grandparents often represent a child’s interests at the expense of those of the parent. Also, since older people contribute less to subsistence than do younger adults, they have more time to play with their grandchildren. It is not surprising that children are willing to live with them or with other close relatives, especially during times of conflict with parents. As one young girl explained, “When I was a little girl, I lived with my aunt for weeks, sometimes for months at a time. I didn’t cry when I lived with her; she was my second mother.”

Fix my voice on the machine so that my words come out clear. I am an old person who has experienced many things and I have much to talk about. I will tell my talk, of the things I have done and the things that my parents and others have done. But don’t let the people I live with hear what I say.

Our father’s name was Gau and our mother’s was Chuko. Of course, when my father married my mother, I wasn’t there. But soon after, they gave birth to a son whom they called Dau. Then they gave birth to me, Nisa, and then my younger brother was born, their youngest child who survived, and they named him Kumsa.1

I remember when my mother was pregnant with Kumsa. I was still small and I asked, “Mommy, that baby inside you…when that baby is born, will it come out from your belly button? Will the baby grow and grow until Daddy breaks open your stomach with a knife and takes my little sibling out?” She said, “No, it won’t come out that way. When you give birth, a baby comes from here,” and she pointed to her genitals. Then she said, “And after he is born, you can carry your little sibling around.” I said, “Yes, I’ll carry him!”

Later, I asked, “Won’t you help me and let me nurse?” She said, “You can’t nurse any longer. If you do, you’ll die.” I left her and went and played by myself for a while. When I came back, I asked to nurse again but she still wouldn’t let me. She took some paste made from the dch’a root and rubbed it on her nipple. When I tasted it, I told her it was bitter.

When mother was pregnant with Kumsa, I was always crying. I wanted to nurse! Once, when we were living in the bush and away from other people, I was especially full of tears. I cried all the time. That was when my father said he was going to beat me to death;2 I was too full of tears and too full of crying. He had a big branch in his hand when he grabbed me, but he didn’t hit me; he was only trying to frighten me. I cried out, “Mommy, come help me! Mommy! Come! Help me!” When my mother came, she said, “No, Gau, you are a man. if you hit Nisa you will put sickness into her and she will become very sick. Now, leave her alone. I’ll hit her if it’s necessary. My arm doesn’t have the power to make her sick; your arm, a man’s arm, does.”

When I finally stopped crying, my throat was full of pain. All the tears had hurt my throat.

Another time, my father took me and left me alone in the bush. We had left one village and were moving to another and had stopped along the way to sleep. As soon as night sat, I started to cry. I cried and cried and cried. My father hit me, but I kept crying. I probably would have cried the whole night, but finally, he got up and said, “I’m taking you and leaving you out in the bush for the hyenas to kill. What kind of child are you? If you nurse your sibling’s milk, you’ll die!” He picked me up, carried me away from camp and set me down in the bush. He shouted, “Hyenas! There’s meat over here…Hyenas! Come and take this meat!” Then he turned and started to walk back to the village.

After he left, I was so afraid! I started to run and, crying, I ran past him. Still crying, I ran back to my mother and lay down beside her. I was afraid of the night and of the hyenas, so I lay there quietly. When my father came back, he said, “Today, I’m really going to make you shit!3 You can see your mother’s stomach is huge, yet you still want to nurse.” I started to cry again and cried and cried; then I was quiet again and lay down. My father said, “Good, lie there quietly. Tomorrow, I’ll kill a guinea fowl for you to eat.”

The next day, he went hunting and killed a guinea fowl. When he came back, he cooked it for me and I ate and ate and ate. But when I was finished, I said I wanted to take my mother’s nipple again. My father grabbed a strap and started to hit me, “Nisa, have you no sense? Can’t you understand? Leave your mother’s chest alone!” And I began to cry again.

Another time, when we were walking together in the bush, I said, “Mommy…carry me!” She said yes, but my father told her not to. He said I was big enough to walk along by myself. Also, my mother was pregnant. He wanted to hit me, but my older brother Dau stopped him, “You’ve hit her so much, she’s skinny! She’s so thin, she’s only bones. Stop treating her this way!” Then Dau picked me up and carried me on his shoulders.

When mother was pregnant with Kumsa, I was always crying, wasn’t I? I would cry for a while, then be quiet and sit around, eating regular food: sweet nin berries and starchy chon and klaru bulbs, foods of the rainy season. One day, after I had eaten and was full, I said, “Mommy, won’t you let me have just a little milk? Please, let me nurse.” She cried, “Mother!4 My br...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1: Earliest Memories

- 2: Family Life

- 3: Life in the Bush

- 4: Discovering Sex

- 5: Trial Marriages

- 6: Marriage

- 7: Wives and Co-Wives

- 8: First Birth

- 9: Motherhood and Loss

- 10: Change

- 11: Women and Men

- 12: Taking Lovers

- 13: A Healing Ritual

- 14: Further Losses

- 15: Growing Older

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Glossary

- Acknowledgments

- Index