- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

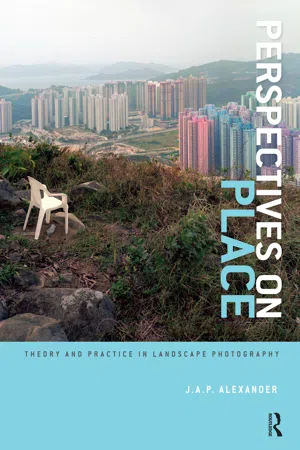

About this book

Perspectives on Place provides an inspiring insight into the territory of landscape photography. Using a range of historic and contemporary examples, Alexander explores the rich and diverse history of landscape photography and the many ways in which contemporary photographers engage with the landscape and their surroundings.Bridging theory and practice, this book demonstrates how mastering a variety of different photographic techniques can help you communicate ideas, explore themes, and develop more abstract concepts. With practical guidance on everything from effective composition, to managing challenging lighting conditions and working with different lenses and formats, you'll be able to build your own varied and creative portfolio.Each chapter concludes with discussion questions and an assignment, encouraging you to explore key concepts and apply different photographic techniques to your own practice. Richly illustrated with images from some of the world's most influential photographers, Perspectives on Place will help you to explore the visual qualities of your images and represent your surroundings more meaningfully.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Perspectives on Place by J.A.P. Alexander in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

TAMING THE VIEW

Fig. 1.1 SUZANNE MOONEY

Benna Beola from the series Behind the Scenes, 2006

In spite of the diversity of technical and conceptual approaches of landscape photographers, they all have these two things in common: an appreciation of the importance of the fundamental processes of photography and an understanding of how these can be controlled or manipulated to create the series of images that they want a wider audience to see. As well as strengthening your understanding of these principles, it is important to consider how technical decisions—the selection of a particular camera or lens or the decision to work in black and white rather than in color—can have a bearing not just upon how someone’s photographs look but also on how he or she might go about making them.

Like other areas of art and design, the composition of the photograph is fundamental to its appearance and appeal, but it also has a great effect on how it is read, in other words, the order in which we process the visual information within a photograph and interpret a message or meaning. This chapter examines how materials and techniques influence the creative process from the perspective of both maker and consumer of landscape photographs. It also considers why we might feel the urge to capture the landscape and reflects on some of the varied ways that narratives are expressed in landscape practice.

Fig. 1.2 TIMOTHY O’SULLIVAN

Vermillion Creek Cañon, 1872

Timothy O’Sullivan was one of several photographers who were commissioned to accompany geologic expeditions as well as document the construction of major infrastructure. Like the medium of photography itself, O’Sullivan’s pictures from these trips sit between a functional, scientific use and something much more enigmatic. O’Sullivan was also one of the most celebrated battlefield photographers of the American Civil War (see p. 164).

Landscape pictures can offer us, I think, three varieties—geography, autobiography, and metaphor. Geography is, if taken alone, sometimes boring, autobiography is frequently trivial, and metaphor can be dubious. But taken together … the three kinds of information strengthen each other and reinforce what we all work to keep intact—an affection for life. ROBERT ADAMS 1

GEOGRAPHY, AUTOBIOGRAPHY, METAPHOR

Before we begin thinking about how landscape pictures can be made, it is pertinent to consider a little of the potential of what landscape images can be or do. There are many philosophies of landscape, boldly defining what demarks it from other genres; however, Robert Adams’s description of three varieties of landscape pictures seems a particularly pertinent point of departure. Adams is one of the world’s most celebrated contemporary landscape photographers and has also written extensively about photography. Each of these varieties touches upon the intent of the photographer, but as we shall see, it is seldom possible to keep each one exclusive from the other.

GEOGRAPHY

Adams’s first category of landscape photography addresses landscape in its most basic state: as an authoritative visual record of a place. It might describe the physical geography—the topography, as well as the weather conditions a place was under at the time—or it may well begin to describe some of the human interactions that take place within the frame. The efforts of the American survey photographers working in the late 1800s offer some interesting historical examples of photographs as geographic records. Timothy O’Sullivan (1840–1882) was one such photographer who joined the geologic survey expeditions of Clarence King to explore and map uncharted areas of the U.S. interior. One of the most famous expeditions was the Fortieth Parallel Survey, which investigated the Great Basin region between 1867 and 1874. O’Sullivan was tasked with creating a photographic record of the expedition and the territories that were surveyed. Intriguingly, King simply asked O’Sullivan to take photographs that “gave a sense of the area,” not necessarily to function as evidential or scientific documents.2

O’Sullivan’s contemporaries included Carleton Watkins (1829–1916), William Henry Jackson (1843–1942), and Andrew Joseph Russell (1829–1902), and they all worked on similar projects as well as on the construction of major infrastructure, such as the Union Pacific Railroad and other industrial enterprises. O’Sullivan’s photographs from the Fortieth Parallel Survey, however, have been recognized as particularly remarkable contributions to landscape practice.3 Unlike the pictures of many of his contemporaries, who tended to compose pictures with the conventions of the picturesque frame, O’Sullivan’s exaggerated and aggressive compositions revealed a relationship to the land that was perhaps a little closer to the truth of it being inhospitable and unwelcoming to the trespassing expeditionaries. Even with modest ambitions, this illustrates the potential of landscape photographs to transcend their purely evidential value.

Thomas Joshua Cooper’s ongoing major body of work, The Atlantic Basin Project, also has a distinctly geographic methodology behind it. For his landscape work, Cooper uses photography to map very precise geographic points and boundaries. For The Atlantic Basin Project, he is assembling pictures from the coastlines and islands around the whole of the Atlantic Ocean, which touches the five continents of the world.

AUTOBIOGRAPHY

Cooper is conscious of the similarity in the appearance of many of his pictures.4 By the nature of the project, they include the sea and the land. They tend to show movement of the water due to the slow shutter of his vintage camera, and despite the importance of location to their making, the tightness of the frame leaves little of topographic significance to the viewer in terms of what is actually there. However, this deliberate homogenization reveals the photographer’s personal intention to use the project to reflect upon the globalized nature of contemporary life: the Atlantic Ocean touches and connects all of us, but perhaps there is a danger that the breaking waves will smother cultural intricacies and differences to the extent that we all become one giant swirling pool. As the title of Fig. 1.3 demonstrates, Cooper’s visual homogenization is deceptive, as each of his photographs—like each of the lives of the citizens who touch the Atlantic Basin—is distinct and unique.

Fig. 1.3 THOMAS JOSHUA COOPER

Freedom Day—Southwest—Table Bay Looking Towards Cape Town and Remembering

Robben Island, Cape Town South Africa, 2004

Thomas Joshua Cooper takes a distinctly geographic starting point for his projects, including his ongoing The World’s Edge: The Atlantic Basin Project, to which this photograph contributes. This simple yet extremely ambitious strategy demonstrates the potential to address more complex themes and offers a personal insight into the mindset of the photographer at the time of exposure. Cooper always works with a 5" × 7" large-format camera, built in 1898.

Fig. 1.4.i–1.4.iv Dewald Botha

Suzhou Ring Road, 2013

Dewald Botha’s Ring Road project illustrates Adams’s three varieties of landscape photography. As well as being a transport system, we could envisage a ring road as being a kind of enclosure: a bird’s-eye view might reveal it as a giant defensive wall. For Botha, the ring roads became a metaphor for the barrier he felt between himself and the people around him.

The element of personal expression is present in almost every photographic act. Most of us use photography to record the things, people, and places that we are fond of or that just grab our attention. While geography and metaphor are also important aspects of Dewald Botha’s Suzhou Ring Road Project, it has a distinctly autobiographical element as well. For Botha, a South African living and working in China, the two ring roads in Suzhou began to signify something far more personal. The roads served as a physical representation of a cultural barrier that placed the native people around him on the “inside,” leaving him on the “outside.” This sense of isolation is communicated in Botha’s photographic strategy. In many of his images, the roads themselves dominate the top section of the frame and cast ominous shadows on the foreground, revealing detail predominantly in the center strip of the frame. This prompts a sense of a constrained view of his surroundings, of myopically looking through the landscape rather than looking at it. This restriction of information might provide a visual translation of Botha’s personal response to this environment, of being able to engage with and participate within it only partially. Botha uses the ring road strategically, as a metaphor for a cultural barrier.

METAPHOR

Adams’s third variety of landscape photography is the means by which we can decipher what might have been going through the photographer’s mind when he or she took a particular photograph. A metaphoric message might be very literal; a photograph that depicts a beach full of holidaymakers is another way of communicating the written description “an overcrowded beach.” However, the same photograph, especially with the aid of a sequence of other photographs, a caption, or the specific context in which it is presented, might allude to something far more interesting. Massimo Vitali has spent much of his artistic career photographing beaches, resorts, and other holiday destinations around Europe. From a casual glance, we could be forgiven for thinking that his photograph Calafuria is just another holiday snap or perhaps belongs to another vernacular context, such as a tourist brochure. Vitali’s approach, however, could not be further from this. He makes his photographs from a customized platform to allow him an elevated vantage point and uses a 10" × 8" view camera, which is equally conspicuous. As the title of Vitali’s series—Natural Habitats—alludes, the photographer’s preoccupation is the study of Europeans at play and, in particular, how this notion of recreation is associated with types of spaces and certain parts of our landscape. Overcrowded Mediterranean beach resorts feature prominently in Vitali’s work, and in this respect, Calafuria is unusual. In fact, strewn across the rocks of this part of the Adriatic coastline, rather than being on the beach, the figures appear to be beached. If images of unfortunate sea mammals or colonies of penguins or other sea birds spring to mind, then metaphor is at work. Without the potential for metaphor, in many instances it wouldn’t be possible to make sense of somebody else’s pictures; they would have little relevance to anyone other than the photographer.

As Adams says, each of these varieties is potentially stagnant without the others. His ethos also touches upon something that the majority of landscape practitioners have in common, from conservative pictorialists to the more inventive: that landscape pictures will fail without an attempt to express a sense of the maker’s perception of it. Adams’s three varieties are useful to b...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Copyright Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction: Where is the Landscape?

- Chapter 1 Taming the View

- Chapter 2 Defining Nature

- Chapter 3 Synthetic Visions

- Chapter 4 Landscape and Power

- Chapter 5 Land Marks

- Conclusion

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index

- Acknowledgments and picture credits