- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Therapeutic counseling in a Christian context can be highly effective when it maintains narrowly focused goals in a time-limited setting. The details of this proven model of pastoral counseling are described in this practical guide.

This second edition of Strategic Pastoral Counseling has been thoroughly revised and includes two new chapters. Benner includes helpful case studies, a new appendix on contemporary ethical issues, and updated chapter bibliographies. His study will continue to serve clergy and students well as a valued practical handbook on pastoral care and counseling.

This second edition of Strategic Pastoral Counseling has been thoroughly revised and includes two new chapters. Benner includes helpful case studies, a new appendix on contemporary ethical issues, and updated chapter bibliographies. His study will continue to serve clergy and students well as a valued practical handbook on pastoral care and counseling.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Strategic Pastoral Counseling by David G. Benner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Ministry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Pastoral Counseling as Soul Care

Pastoral Counseling as Soul Care

Although pastors have been providing spiritual counsel as a part of their overall soul-care responsibilities since the earliest days of the church, what we today think of as pastoral counseling is a relatively recent phenomenon. In his History of Pastoral Care in America (1983), Holifield dates its development to the first decade of the twentieth century when a group of New England pastors first began to consider how the newly developed procedures of counseling and psychotherapy could be put into spiritual use by the church.

Contemporary pastoral counseling has grown up alongside general psychological counseling—both being fruits of the twentieth-century “triumph of the therapeutic” (Rieff 1966). Attempting to find its identity within this therapeutic culture, pastoral counseling has often experienced tension between the pastoral and the psychological. Some forms of pastoral counseling have borne more resemblance to modern psychotherapy than to historic Christian soul care. Other pastors have sought to distance themselves entirely from psychological counseling, seeking simply to offer biblically based spiritual counsel.

But there is a middle road between mimicking current psychological fads and ignoring the contributions of modern therapeutic psychology. Pastoral counseling can be both distinctively pastoral and psychologically informed. This occurs when it takes its identity from the rich tradition of Christian soul care and integrates appropriate insights of modern therapeutic psychology in a manner that protects both the integrity of the pastoral role and the unique resources of Christian ministry.

Christian Soul Care

The English phrase “care of souls” has its origin in the Latin cura animarum. While cura is most commonly translated “care,” it actually contains the idea of both care and cure. Care refers to actions designed to support the well-being of something or someone. Cure refers to actions designed to restore well-being that has been lost. The Christian church has historically embraced both meanings of cura and has understood soul care to involve nurture and support as well as healing and restoration.

But what does it mean to identify the soul as the focus of this care and cure? “Soul” is the most common translation of the Hebrew word nepesh and the Greek word psyche. Many biblical scholars suggest, however, that a better translation is either “person” or “self.” The soul is not a part of a person but his or her total self. We do not have a soul; we are soul—just as we are spirit and we are embodied. A human being is a living and vital whole. “Soul,” therefore, refers to the whole person, including the body, but with particular focus on the inner world of thinking, feeling, and willing. Care of souls can thus be understood as the support and restoration of the well-being of a person in his or her depth and totality, with particular concern for the inner life.

Caring for souls is caring for people in ways that not only acknowledge them as persons but also engage and address them in the deepest and most profoundly human aspects of their lives. This is the reason for the priority of the spiritual and psychological aspects of the person’s inner world in soul care. It is these aspects of life that mark us most distinctively as human. But genuine soul care is never exclusively focused on any one aspect of a person’s being to the exclusion of all others. If care is to be worthy of being called soul care, it must not address parts or focus on problems but engage two or more people with one another to the end of the nurture and growth of the whole person (Benner 1998).

Over the course of its long history, Christian soul care has had varied expressions but has always been a central part of the life and mission of the church. Reviewing this history, Clebsch and Jaekle (1964) note that such care has involved four primary elements: healing, sustaining, reconciling, and guiding. Healing involves efforts to help someone overcome an impairment and move toward wholeness. These curative efforts can involve physical healing as well as spiritual healing, but the focus is always the total person, whole and holy. Sustaining refers to acts of caring designed to help a hurting person endure and transcend a circumstance in which restoration or recuperation is either impossible or improbable. Reconciling refers to efforts to reestablish broken relationships. The presence of this component of care demonstrates the communal, not simply individual, nature of Christian soul care. Finally, guiding refers to helping a person make wise choices and thereby grow in spiritual maturity.

Christians seeking to care for the souls of others have heard confessions, given counsel, offered consolation, preached sermons, written books and letters, visited people, developed and run hospitals, organized schools and offered education, and engaged in social and political activities. All these and many more things have been undertaken to the end of what McNeil describes as “the presentation of all people perfect in Christ to God” (McNeil 1951, vii). This suggests that the overarching goal of Christian soul care may be thought of as spiritual formation, the formation of the character of Christ within his people.

Twentieth-century soul care has become narrowed by the clinical and therapeutic approach to persons that has become dominant both inside and outside the church. Care has been largely overshadowed by cure as clergy and laity alike have been displaced by counselors as the preferred providers.

Christian soul care is, however, much too important to be restricted to the curative activities associated with modern clinical therapeutics. It is also much broader than counseling— even pastoral counseling. Understanding where pastoral counseling fits within the spectrum of Christian soul care is essential if it is to fill its distinctive and most important niche.

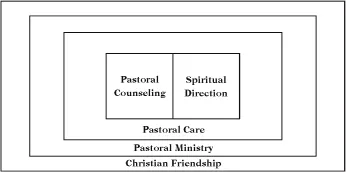

At least five forms of soul care should be a part of the life of every Christian church: Christian friendship, pastoral ministry, pastoral care, pastoral counseling, and spiritual direction.1 The continuum that they form is a continuum of specialization— moving from broadest and least specialized to narrowest and most specialized. It is not a continuum of importance. The relationship of these forms of soul care is depicted in figure 1.

Figure 1

The Context of Pastoral Counseling

The Context of Pastoral Counseling

Christian Friendship

The foundation of Christian soul care is its least specialized form—the friendship offered by one Christian to another.2 Friends do not think of themselves as offering soul care when they call one another to offer support or encouragement or simply to maintain contact. They are simply caring for those they love. But friends who understand the high ideals of Christian companionship offer one of the most important forms of Christian soul care. And if we could more regularly be in relationships in which friends and family cared for us in our totality with particular attention to the inner self, the need for more formal and specialized expressions of soul care would be greatly reduced.

Christian friendship is both important and possible because it has its source in God. The Christian doctrine of the Trinity places friendship at the very heart of the nature of God. And almost unbelievably, the eternal exchange of companionship that binds Father, Son, and Holy Spirit to one another extends to those Jesus calls to be his followers and friends. It is this friendship that Jesus asks us to show to one another (1 John 4:7).

At its best, the care that family members and friends give to one another has the unique potential to encourage deep growth and healing. Parents, as they nurture the psychological and spiritual aspects of their children, have opportunities to influence their children in ways that no one else will ever have, as do couples who make a genuine effort to know and support the inner life of their spouse.

Unfortunately, families often fail to live up to the ideals of soul friendship. Parents content themselves with discipline and instruction, failing to offer themselves also in a gift of friendship. Tragically, of course, couples easily and regularly do the same. Too often those who are active in caring for others outside the home offer little genuine soul friendship to those within their own family.

Churches that seek to establish the mutual soul care offered between friends and family members as the foundation of the soul care provided by the congregation must start by helping families become networks of genuine soul friendship. They must both encourage and support friendships between non-family members that do not resemble mere generic fellowship but reflect nothing less than the ideals of mutual soul care.

Pastoral counseling is not friendship, nor can it be offered without hazard to someone with whom the pastor has a personal friendship.3 But pastoral counseling can best fulfill its distinctive role when it is offered within a community that is based on a network of genuine soul-care friendships.

Pastoral Ministry

Pastoral ministry also forms part of the broad context of pastoral counseling. It includes such things as preaching, teaching, leading worship, administration, community service, leadership development, and, of course, pastoral care and counseling (Clinebell 1984). Although the boundaries among these spheres of responsibility are sometimes unclear, it is important that these diverse activities fit together as a whole. Thus, no one activity can be undertaken in a way that compromises others. This is particularly important in the case of pastoral care and counseling, which can easily consume time intended for other responsibilities and which can be entered into in a way that produces significant conflict with other aspects of the pastoral role. Pastoral counseling must, therefore, be conducted in a way that minimizes conflict with these other pastoral roles.

Preaching, teaching, and worship are all particularly vital soul-care activities. Anything that brings people into contact with God nurtures the growth of their spirits and heals their souls. This is why most pastors rightly understand worship as central to the life of a congregation. We can think of it as corporate soul care in that, at its best, it integrates and gives direction to all the other forms of soul care offered within a congregation.

Pastoral counseling must be offered in such a way as to support, never compromise, these broader responsibilities of pastoral ministry. Most pastors, except for those who do only counseling, must fit counseling within the range of other responsibilities that fill the week. This means it must fit not only within available and limited time (about which I will have more to say shortly) but also within the network of other roles the pastor fills.

One area of potential conflict is between counseling and preaching. Should sermons be drawn from one’s counseling experiences? To do so, in a direct and obvious manner, violates the confidentiality of the counseling encounter. One must realize that respecting this all-important counseling norm of confidentiality requires more than protecting a person’s name (Nessan 1998). Even if one has planned a sermon on homosexuality, for example, it is probably not a good idea to give it right after hearing about a parishioner’s struggles in this area. Doing so would undoubtedly make the parishioner feel that the pastor was using the pulpit to say something to him or her specifically.

But on the other hand, to fail to allow one’s preaching to be informed by one’s counseling is to fail to utilize a rich source of information about one’s congregation and to speak dynamically to their deepest needs. The answer to this dilemma lies, of course, in Spirit-guided discernment about when and how to address such issues. The pastor should also not overlook the simple option of discussing the sermon topic with the individual concerned. This is an easy way to show sensitivity and can be the ounce of prevention that saves the pound of remediation.

Pastoral Care

Pastoral ministry is broader than pastoral care; so too, pastoral care is broader than pastoral counseling. To attempt to reduce all pastoral care to counseling is to fail to recognize both the breadth of pastoral care as well as the distinctive nature of counseling.

As the term is commonly employed, pastoral care refers to the total range of help offered by pastors, elders, deacons, and other members of a congregation to those they seek to serve. Pastoral care is a ministry of compassion, and its source and motivation is the love of God. In its most basic form, pastoral care is simply a Christian reaching out with help, encouragement, or support to another at a time of need.

Pastoral care is the gift of Christian love and nurture from one who attempts to mediate the gracious presence of God to another who desires, to one degree or another, to live life in the reality of that divine presence.

Eschmann (2000) suggests that pastoral care includes three broad types of activities: blessing and healing, reconciliation and conversion, and sanctification and fellowship. More specifically, it includes such things as visiting the sick, attending to the dying, comforting the bereaved, encouraging reconciliation of the estranged, supporting those who are struggling or facing difficulties of any kind, nurturing and protecting the faith of those within the congregation, preaching, teaching, intercessory prayer, and administering the sacraments.

Healthy congregations build on the foundation of friendships that form the core of spiritual community by encouraging all Christians to reach out to one another in relationships of pastoral care. Describing all acts of Christian care as “friendship,” however, trivializes friendship. Friendships should be mutual, whereas acts of pastoral care should be offered with no expectation of anything in return. Congregations that include an ever increasing number of members and adherents who are concerned about the welfare of others within the fellowship are congregations that place soul care at the heart of ministry.

Pastoral counseling is also an activity of pastoral care, though it differs from these other pastoral-care activities in several important ways. First, whereas a relationship of pastoral care can appropriately be initiated by a pastor or someone else offering care, pastoral counseling is usually initiated by a parishioner. Furthermore, pastoral counseling typically has more of a problem focus; that is, a parishioner contacts the pastor because of something that is problematic and for which he or she seeks help. While pastoral care may be delivered in the face of difficult life experiences, these are usually seen not so much as problems that need to be solved as experiences that need to be understood theologically and faced with the awareness of the presence of God.

Pastoral-care activities also usually involve less time than is the case with pastoral counseling—even a brief form of counseling such as strategic pastoral counseling. Acts of marriage, burial, or visitation do not usually involve an ongoing relationship of pastoral care. Even marriage preparation (sometimes called premarital counseling but usually lacking the problem focus of other forms of counseling) is typically time-limited.

Furthermore, pastoral care does not require the same level of involvement or responsiveness that is necessary in pastoral counseling. It is quite appropriate, for example, to offer pastoral care to people who are unconscious (see, for example, Close 1998), nonverbal, or even profoundly mentally retarded—all conditions that would suggest limited usefulness for pastoral counseling.

Finally, whereas in other pastoral-care activities, biblical precepts are sometimes appropriately introduced immediately and directly, in pastoral counseling, sharing passages from the Bible is not appropriate u...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Preface to the First Edition

- 1. Pastoral Counseling as Soul Care

- 2. The Uniqueness of Pastoral Counseling

- 3. The Strategic Pastoral Counseling Model

- 4. The Stages and Tasks of Strategic Pastoral Counseling

- 5. Ellen: A Five-Session Case Illustration

- 6. Bill: A Single-Session Case Illustration

- Appendix: Ethical Considerations in Pastoral Counseling

- References