eBook - ePub

Handbook on the Historical Books

Joshua, Judges, Ruth, Samuel, Kings, Chronicles, Ezra-Nehemiah, Esther

- 560 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Handbook on the Historical Books

Joshua, Judges, Ruth, Samuel, Kings, Chronicles, Ezra-Nehemiah, Esther

About this book

From the tumbling walls of Jericho to a Jewish girl who became the queen of Persia, the historical books of the Bible are intriguing and unquestionably fascinating. In this companion volume to his Handbook on the Pentateuch, veteran Old Testament professor Victor Hamilton demonstrates the significance of the messages contained in these biblical books.

To do so, Hamilton carefully examines content, structure, and theology using rhetorical criticism, inductive Bible study techniques, published scholarship, archaeological data, word studies, and text-critical evidence. Hamilton details the events and implications of each book chapter by chapter, providing useful commentary on overarching themes and the connections and parallels between Old Testament texts. Using theological and literary analysis, this comprehensive introduction examines historical issues, attempting to uncover and discover their thrust and theological messages. For those who wish to do additional research, each chapter is appended with a bibliography.

Undergraduate students of advanced biblical studies will find this volume enlightening and helpful as they forge their way through the historical books, and pastors will find useful insight for their encounter with and exposition of this portion of Scripture.

To do so, Hamilton carefully examines content, structure, and theology using rhetorical criticism, inductive Bible study techniques, published scholarship, archaeological data, word studies, and text-critical evidence. Hamilton details the events and implications of each book chapter by chapter, providing useful commentary on overarching themes and the connections and parallels between Old Testament texts. Using theological and literary analysis, this comprehensive introduction examines historical issues, attempting to uncover and discover their thrust and theological messages. For those who wish to do additional research, each chapter is appended with a bibliography.

Undergraduate students of advanced biblical studies will find this volume enlightening and helpful as they forge their way through the historical books, and pastors will find useful insight for their encounter with and exposition of this portion of Scripture.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Handbook on the Historical Books by Victor P. Hamilton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Biblical Criticism & Interpretation. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Samuel

We can be fairly certain that originally First and Second Samuel formed one book. The division into two books may have been done early in the Christian era, but was anticipated by the Septuagint, the translation of the Hebrew Bible into Greek, in the pre-Christian centuries. The Septuagint (represented by the symbol LXX, the Roman numeral for 70) considered Samuel and Kings one unified composition called “The Book of Kingdoms.” Hence, the four subparts of the Book are Kingdoms Alpha, Kingdoms Beta, Kingdoms Gamma, and Kingdoms Delta.

The Latin Vulgate followed the LXX at this point, except that it changed “Kingdoms” to “Kings” and used Roman numerals instead of letters of the Greek alphabet: I Kings; II Kings; III Kings; IV Kings. This practice is still followed by some Roman Catholic Bibles.

A Hebrew manuscript from the 1400s A.D., undoubtedly relying on a much older precedent, divides Samuel into two books. This division was adopted by the famous Bomberg Bible of 1517 and by all subsequent Protestant Bibles.

The point in the biblical narrative where the story is divided into two different books is, admittedly, strange, but not without rhyme or reason. For example, it is somewhat unexpected that the story of King David does not end in the last chapter of Second Samuel, but rather in the second chapter of First Kings, after Solomon has ascended the throne. Or again, Saul’s death is recorded in the last chapter of First Samuel. But then there follows another “account” of his death in 2 Sam. 1:1–16 and David’s elegy over Saul and Jonathan (2 Sam. 1:17–27). Most likely, the commencement of Second Samuel with material primarily about Saul is intended to shift the focus, even of Saul’s death, to the figure of David (Childs 1979: 272). What does Saul’s demise mean for David not only in terms of opportunity, but also in terms of his own feelings for his predecessor?

It is interesting that the next two books after Ruth bear the name “Samuel.” He certainly cannot be the author of them, for his death is recorded in 1 Sam. 25:1. Again of interest, Samuel, now old and gray, delivers his last words in 1 Sam. 12:1–25 (like Moses in Deut. 31:1–8 and Joshua in Josh. 24:1–28), but he goes on living until 1 Sam. 25:1, some years later! Certainly, Samuel must be responsible for some of the material in First Samuel. We can adduce that from 1 Chron. 29:29, which says, “Now the acts of King David, from first to last, are written in the records of the seer Samuel,” and from 1 Sam. 10:25 which says, “Samuel told the people the rights and duties of the kingship; and he wrote them in a book.”

If Samuel’s primary connection with the book(s) that bears his name is not authorship, then that primary connection must be the monumental spiritual stature of Samuel and the far-reaching shadow of influence he cast over his own generation and generations to come. Judging from Jer. 15:1 (“Though Moses and Samuel stood before me”), one concludes that these two men are the two great spiritual forces of premonarchic Israel. One finds a possible similar coupling in the words of the eighth-century prophet Hosea: “By a prophet [Moses] the Lord brought Israel up from Egypt, and by a prophet [Samuel?] he was guarded” (Hos. 12:13).

Several factors underscore Samuel’s significance. First, he bridges the transition from Israel’s confederacy in the days of the judges to monarchy. Second, in conjunction with the first, he bridges the gap between the former charismatic age and the forthcoming prophetic era. Third, he bridges the gap between an exclusively entrenched hierarchy of religious functionaries—the priests—and an upsurge of prophetic spiritual leaders. History is replete with the ongoing struggle in religious communities between hierarchy and charism.

In the opening chapters of First Samuel we find the established clergy (the house of Eli) replaced by a new leader (Samuel) from the ranks of the laity (Albright 1963: 44). For similar movements, one thinks of the Essenes, who turned their back on a corrupt Jerusalem priesthood; or the Pharisees, who began preparing teachers/rabbis to replace priests as leaders of the community; or the Lutherans and Calvinists ordaining pastors instead of priests; or John Wesley, a Tory Anglican, ordaining lay preachers; or parachurch movements, often led by laity and often having a much wider sphere of influence than mainline denominational ministries.

There seems to be a discrepancy about Samuel’s tribal background. According to 1 Sam. 1:1, Samuel is from the tribe of Ephraim, one of the laic tribes. Yet, according to 1 Chron. 6:27–28 (see especially the NIV), he is a Levite from a family of singers. Is Samuel from a laic tribe or a clerical tribe? These two traditions may be harmonized by suggesting that though technically a layperson from the tribe of Ephraim, as a Nazirite devoted by his mother to service at the sanctuary in Shiloh and there performing Levitical functions, he may well have been considered by later genealogists as a Levite.

In one sense, what we call “First Samuel” could as well be called “The Book of Samuel and Saul.” If Samuel occupies center stage in chs. 1–12, Saul occupies center stage in chs. 13–31. But Eli is present in the first portion of the book and David in the latter. Accordingly, we suggest a threefold division of First Samuel with a human pair in each division, usually in some kind of an adversarial relationship:

I. 1–7: Samuel and Eli (prophet versus priest)

II. 8–15: Samuel and Saul (prophet/archbishop versus king)

III. 16–31: Saul and David (king versus successor)

I. 1–7: Samuel and Eli

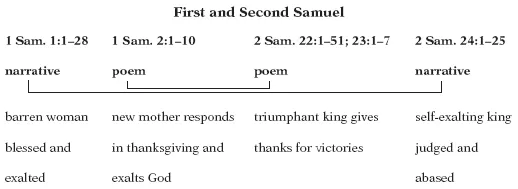

1:1–28. We owe to Brevard Childs (1979: 272–73) the observation about the significance of the placement of poems near the beginning (1 Sam. 2:1–10, the Prayer of Hannah) and end (2 Sam. 22:1–51; 23:1–7, the Song of David) of Samuel. It is as if these two poems, one sung by a woman, one sung by a man, act as bookends to Samuel. Both celebrate in thanksgiving form the faithful workings of Yahweh.

However, the Prayer of Hannah does not begin First Samuel, nor does the Song of David end Second Samuel. Preceding the Prayer of Hannah is the narrative about Samuel’s birth and consecration, and how a barren wife is blessed with a child (1:1–28). And following the Song of David is the narrative about David taking a census (2 Sam. 24:1–25). At the beginning of this episode David appears as a proud, vain man glorying in his resources. By narrative’s end David is reduced to contrition and penitence. Thus, Hannah in 1 Samuel 1 and David in 2 Samuel 24 are traveling in different directions: she from abasement to a position of honor; he from a position of honor to abasement.

Thus, if we should connect the poems that come near the beginning of First Samuel and the conclusion of Second Samuel, then we should also connect the narratives with which First Samuel begins and Second Samuel ends. They also are bookends framing the whole (Brueggemann 1990: 44).

One can quickly see that Hannah’s poem is an appropriate response to the narrative details of ch. 1 of First Samuel. The barren one becomes the doxological one. But the narrative of 2 Samuel 24 is not an appropriate sequel to the poems of 2 Samuel 22 and 23. The victorious, thankful one becomes the egocentric, self-exalting one.

First Samuel 1 falls into two basic parts: (1) vv. 1–8, which provide the necessary background information that follows in (2) the narrative of vv. 9–28. We are first introduced to Samuel’s father, Elkanah, whose family tree is traced quickly back through four generations of Ephraimites. “The names in Elkanah’s genealogy are important because of their unimportance” (Eslinger 1985: 67). Whatever later claim to fame Samuel may have, it is not because his ancestry is a biblical who’s who.

Further, we are told he had two wives (not unlike many other men in the Old Testament), one of whom is fertile (Peninnah), and one of whom is barren (Hannah [“the gracious one”]).

Three people are particularly unhelpful and insensitive to Hannah. The first is her rival co-wife and provocateur, Peninnah, who taunted and insulted Hannah year after year (vv. 6–7). The second is her husband, Elkanah, who “hammers” (Fokkelman 1993: 31) her with four staccato questions (v. 8). His questions are not just probing but actually plaintive, especially his last one: “Am I not more to you than ten sons?”—as if to say, “Am I not all the men in your life you really need?”

The third culprit is Eli the priest, who interprets Hannah’s silent praying, with only the moving of her lips, as drunkenness (vv. 13–14)—hardly an indication of pastoral sensitivity. To be sure, it would appear from other texts throughout the Old Testament that prayer recited aloud was the normal practice. (Interestingly, later Jewish practice urged that the faithful recite their central prayer, known as the ʿAmida or Shemoneh ʿEsreh, in a whisper, using Hannah’s prayer as the model. See in the Babylonian Talmud Berakot 31a and in the Jerusalem Talmud Berakot 4:1.)

Hannah is capable of admonishing her “pastor” and setting him straight about the nature of her activities (vv. 15–16).

At the heart of all this is Hannah’s vow (v. 11). It is in most ways like other biblical vows (see our discussion on pp. 144–45), but with one fundamental difference. All of the other vows we mentioned earlier went something like this: “If you [God] do such-and-such, then I will do such-and-such.” Hannah’s is a bit different. She says, “If you [God] give me so-and-so, I will give you back so-and-so.” To put it a bit differently, the other vows say, “If you will do X, then I will do Y,” in a sort of quid pro quo fashion (Polzin 1989: 24). But Hannah says, “if you will give me X, then I will give you X” (Fokkelman 1993: 29). This means, then, that Samuel is not only a gift from God, but also a gift to God (Walters 1988: 399).

A key word throughout this section is “ask,” root shʾl. It occurs no fewer than nine times:

v. 17: “Then Eli answered, ‘. . . the God of Israel grant your asking that you have asked of him.’”

v. 20: “She named him Samuel, for she said, ‘I have asked him of the Lord.’”

v. 27: “And the Lord has granted me my asking that I asked of him.”

v. 28: “Therefore I have caused [or, ‘lent’] him to be asked for by the Lord. All the days of his life he is the asked-for one [or, ‘he is Saul/Sha’ul’].’

2:20: “Then Eli . . . would say, ‘May the Lord repay you with children by this woman for the asking that she asked of the Lord.’”

Now several things may be noticed about the uses of “ask” in chs. 1 and 2. First, the name “Samuel” is not per se to be connected with the verb “ask.” Samuel probably means something like “the name of God” or “his name is God.” Second, what we have here is not a case of literal etymology, but alliterative etymology. That is to say, both “Samuel” and “ask” begin with the consonant sh—shemuʾel, shaʾal—just as both end with the letter l. Third, Hannah is not so much interested in explaining why she named the child “Samuel,” as much as she is in proclaiming that this baby is a gift from God in divine response to petitionary prayer.

Fourth, we may notice that one more time in Samuel somebody asks God or his representative for something, and that is the occasion when the people “ask” Samuel to appoint a king over them (8:10; 12:13, 17, 19, all sing shaʾal). Polzin (1989: 24–25) creatively suggests that Hannah’s asking God for a child is a parabolic foreshadowing of Israel asking Samuel (and God) for a king. Peninnah has sons; Hannah does not. Israel’s neighbors have kings; Israel does not. Hannah appears drunk, but is not. Kingship appears inherently evil, but is not. Elkanah is worth more to Hannah than ten sons—or so he believes, and Yahweh is worth more to Israel than ten kings.

It is this connection between these two episodes that makes most sense out of Hannah’s comments on her newborn’s name. At first look they seem to explain more the name of “Saul” than of “Samuel.” In fact, many scholars assert that ch. 1 actually describes the naming of Saul, which only later unadvisedly was transferred to Samuel.

There are two “asked-for” ones in this era in the Old Testament. There is the shaʾul, who is the son of Hannah, and later there is the shaʾul, who is the son of Kish. “An important and divinely acceptable Saul . . . will have already been at work for decades before the birth of the Benjaminite we know as king Saul” (Fokkelman 1992: 56).

2:1–10. It is not infrequent in Scripture to encounter a praiseful, poetic response by an individual on the heels of a gracious act by God. One thinks, for example, of the Songs of Moses and Miriam (Exod. 15:1–21) as a celebratory response to God’s deliverance of Israel at the sea as the Egyptians pursued them, or of the Song of Deborah that celebrates Yahweh’s victory over the Canaanites and their charioteers (Judg. 5:2–31). That is what we have here. God has given barren Hannah a child. Mother Hannah consecrates that child to God. Then she pray...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Abbreviations

- Preface

- Joshua

- Judges

- Ruth

- 1 Samuel

- 2 Samuel

- 1 Kings 1-11

- 1 Kings 12-2 Kings 25

- 1-2 Chronicles

- Ezra-Nehemiah

- Esther

- Subject Index