eBook - ePub

Biblical Concepts for Christian Counseling

A Case for Integrating Psychology and Theology

- 230 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Biblical Concepts for Christian Counseling

A Case for Integrating Psychology and Theology

About this book

Kirwan not only sounds a clarion call for thorough integration of psychology and theology, he demonstrates that it can be done.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Biblical Concepts for Christian Counseling by William T. Kirwan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Four Basic Counseling Positions

My wife Anne has a close friend who had to be hospitalized not long ago for fear that she might commit suicide. For thirteen years she has been handicapped by chronic depression, destructive relationships, feelings of worthlessness, lack of confidence. A talk I had with her before her hospitalization convinced me that she has a firm commitment to Christ and the Bible, even though she finds it difficult to trust the Lord on a daily basis. She said she has never been able to fully trust anyone.

How can a person with strong Christian convictions, a person who has experienced love and prayer among other believers, and participated in Bible studies and the fellowship of a vital church, fall apart? When such an event occurs, what is the effect on the cause of Christ? Does it invalidate the Christian faith? Does it cast doubt on Christ’s power to restore people to mental health? Anne wondered if those Christians who offer simplistic answers could even begin to understand the complexity of our friend’s problem.

A lot of confusion exists about how Christianity relates to mental health. Through my work as a minister and psychologist, I have discovered that there are basically four views of the relationship between Christianity and psychology and, accordingly, four basic counseling positions.

One psychologist friend—with outstanding professional credentials—believes “religion” to be good and worthwhile. He contends, however, that empiricism and the laws of psychology rank above the essential elements of the Christian faith. Religion, if it fits into the process of aiding a patient’s ability to cope with problems, is acceptable but not essential. While biblical concepts may occasionally be of some value in the therapeutic process, they must never be allowed to interfere with its basic course. This view, which I will call the un-Christian view, is probably held by a majority of mental-health professionals. They are likely to insist that religion, or more specifically biblical Christianity, has nothing to offer individuals like our depressed friend. Some would even contend that Christianity caused or contributed to some of her problems.

On the other hand, I know a pastoral counselor who looks at all emotional disturbances as spiritual problems. He believes that all depression and despair result from violating certain scriptural principles. He argues that obeying God’s Word is the answer to all mental problems. He considers repentance and confession of conscious sin the key to healing. I call this the spiritualized view. I held this position while I was in seminary and I argued vehemently for it. I remember reading Gilbert Little’s Nervous Christians several times in my college years. According to the author, “when Christ enters into the individual’s soul and self is crucified, the symptom complex common to nervous patients will not develop in textbook style, because the Christian then goes in the power of Christ instead of self.” In spite of its kernel of truth, Little’s outlook now seems to me to be simplistic and incompatible with both psychological and biblical data. I know from experience, including personal therapy, that spiritualized answers like that, given to suffering Christians with real problems, are actually cruel and heartless. Moreover, the Bible speaks often about mental suffering as a reality of life.

A third counselor represents the parallel view. He believes in the principles of psychology and is skilled in their application. He knows Christ in a real way and understands the Bible well, yet there is little overlap between his Christianity and psychology. Each seems to function independently of the other, so that biblical words like “sin,” “guilt,” and “faith” are replaced in the counseling office by terms like “acting out,” “intropunitive reaction,” and “obsession.” Counselors who stress data from both the Bible and science, but do not integrate them, are closer to the truth than are either of the first two counselors I mentioned, yet something is amiss in their approach.

Finally, I think of a fourth counselor. He also has a vast appreciation of psychology and skill in its application as well as a serious commitment to Christ and the Bible. But he holds an integrated view, which does not see the Bible and psychology as functioning independently in different spheres. This counselor has an ability to put together the truths of psychology and the Bible in a harmonious way. I admire his gift for showing how psychological understanding can often enlighten a great biblical truth.

Biblical Christianity and psychology, when rightly understood, do not conflict but represent functionally cooperative positions. By taking both spheres into account, a mental-health professional can help Christians avoid the inevitable results of violating psychological laws structured into human personality by God. Our suicidal friend was exposed to all four approaches. She found lasting help, however, only from a counselor who used an integrative approach. Therefore, it seems to be incumbent on psychologists in the evangelical camp to integrate their counseling theories and methods with the Word of God. At present only a few counselors seem able to combine the two.

In Part One of this book I will examine in greater detail each of the four positions mentioned above and demonstrate that the integrated view is the best. Indeed, the biblical presentation itself virtually demands that the data of psychology and of Scripture be integrated. In Part Two I will endeavor to present a theological perspective integrating psychology and Scripture, including a discussion of the fall and our experience of its emotional consequences today. In Part Three I will present my own model for counseling, which I believe thoroughly integrates psychological theory with God’s Word.

The Necessity of Identifying Presuppositions

To critique the four basic views of the relationship between Christianity and psychology, we must make a clear assessment of the differences between these views and of their individual strengths and weaknesses. But before we can do that, we must identify the presuppositions underlying each of the four basic counseling positions.

Each person’s overall world-view rests on a presupposition or basic assumption. Francis Schaeffer defines presupposition as “a belief or theory which is assumed before the next step in logic is developed. Such a prior postulate then consciously or unconsciously affects the way a person subsequently reasons” (Schaeffer 1968, 179). Through careful analysis, each person’s philosophy or belief system, however elaborate, can be traced back to a clearly defined starting point or presupposition.

All counseling theories have philosophical presuppositions at their core. Those basic assumptions lead to certain logical conclusions concerning the human person, behavioral change, and meaning in life.

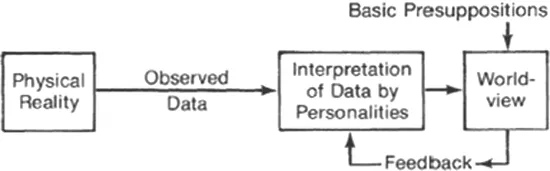

The operation of presuppositions is illustrated in Figure 1. “Physical reality” refers to the natural world, which can be studied scientifically. “Observed data” are the facts noted about that world, ranging from casual impressions during a lunch discussion to observation of cells under a microscope or clinical notations of the thoughts and emotions of an individual being counseled. The observed data are then interpreted according to the observer’s unique thought patterns or constructs, and the interpreted data are fed into his “world-view,” which is based on his fundamental presuppositions. The interpreted data reinforce and further solidify the world-view by expanding its horizons and complexity. But in turn, “feedback” from the world-view influences the interpretative processes and hence the assimilation of data.

FIGURE 1 The Operation of Presuppositions (based on a figure in David L. Dye, Faith and the Physical World [Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1966], p. 71)

In practice, we select the data and interpretations that best suit our world-view, and that world-view, in turn, is rooted in our presuppositions. Only those who fail to understand the circularity of the process could ever assert that a particular world-view is scientifically proven. The presuppositions at the foundation of every world-view are beyond the ability of science to prove or disprove.

Clearly, one’s world-view is determined not simply by data input, but also by whatever basic presuppositions underlie the entire process. The process is circular, starting and finishing with the underlying presuppositions as one attempts to make both old and new data compatible with one’s presuppositions. Philosopher Michael Polanyi emphasized that the inherent structure of the “act of knowing makes us both necessarily participate in its shaping and acknowledge its results with universal intent” (Polanyi 1964, 65). Walter Thorson sums up Polanyi’s major thesis: “There is no knowledge apart from the knower’s, and the personal participation of the knower in that which he knows is both pervasive and inescapable” (Thorson 1969, 41).

Astronomer Robert Jastrow has described the reluctance of some leading astronomers to accept the evidence that the universe originated with a “big bang.” Their presupposition that there is no God seems to be influencing their scientific outlook. Jastrow points out that their response is based on emotions, not evidence:

There is a strange ring of feeling and emotion in [their reactions]. They come from the heart, whereas you would expect the judgments to come from the brain. . . . As usual when faced with trauma, the mind reacts by ignoring the implications. . . . For the scientist who has lived by his faith in the power of reason, the story ends like a bad dream. He has scaled the mountain of ignorance; he is about to conquer the highest peak; as he pulls himself over the final rock, he is greeted by a band of theologians who have been sitting there for centuries. [Jastrow 1978, 113–16]

Jastrow’s article illustrates Polanyi’s thesis that, in part, personal internal or subjective thought patterns will be superimposed on the external data and the objective world. That kind of participation of the knower is, quietly and subtly, a major part of knowing it rests on commitment to certain postulates the knower holds to be true.

Thus, data do not exist as neutral or brute facts but are always interpreted by the observer. For example, a theist who discovers a fact interprets it as a God-created fact; an atheist interprets the same fact as a non-God-created fact. Agnosticism is a difficult position to hold consistently, since brute facts cannot be perceived or understood without being interpreted in accordance with some kind of world-view. Because data must necessarily be interpreted, even the most scientific psychological investigation is a highly human activity drawing on the conscious and unconscious personality, interests, ideals, and aspirations of the observer.

The Presuppositions of Science and Christianity

Before we can identify the presuppositions underlying the four basic views of the relationship between psychology and Christianity, we must determine the presuppositions of psychology (the science of mental processes and behavior) and of Christianity. Both science as a discipline and the mindset of the scientist who practices the art rest on specific presuppositions. Edwin Burtt pointed out in his Metaphysical Foundations of Modern Science that an individual cannot operate as a scientist, cannot put on a white coat and go into a laboratory, without taking along at least three basic assumptions. First, scientists presuppose reality. They believe that the world is real and observable, that it can be studied, and that through such research legitimate data are achievable. Second, scientists presuppose causality: some type of causal law applies throughout the whole of reality. Some causal relationship exists between the various states of the universe. The principle of causality means that every state of the universe is related to all other states of the universe. A third assumption scientists make is that physical reality and the human mind’s verification of that reality are logical and rational. If the human mind were not logical and rational, science could not study physical reality.

Obviously, atheists and other non-Christians have investigated nature. But on what basis can such scientists assert that the world is real, that what is observed as reality today will be reality tomorrow? For atheists, the basic assumption is that the world is here by chance, that a fortuitous collision of molecules is responsible for the universe, the earth, and human beings. (“Chance” is used here as a philosophical term denoting purposeless randomness, not as a scientific term denoting the mathematical probability of a certain event.) How can an individual whose basic assumption is that the world is a chance occurrence assert that the universe is constant and consistent?

On the other hand, those that believe that God exists and that He is the maker and sustainer of the universe do have a firm basis for scientific work. Christians can assert: “It is possible for human beings to observe nature because God has made it and it is real. We can assume causality, because God has created a consistent world with cause and effect built in. Further, God has made the human person capable of logical thought, which can be applied not only in matters of science but also in other areas of human endeavor.”

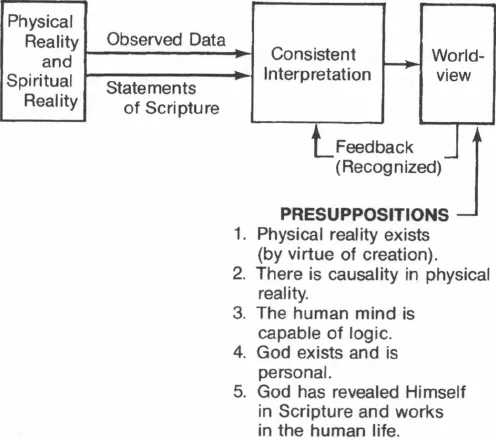

Christians also believe that reality extends beyond what can be observed and measured. Christians believe in a personal God who has revealed Himself in Scripture. The spiritual and psychological assertions of Scripture are true, although many of them cannot be scientifically examined. The Christian world-view includes spiritual and psychological dimensions beyond the observable physical reality.

The Christian world-view is depicted in Figure 2. Note that while the Christian world-view goes beyond the scientific world-view (presuppositions 4 and 5), the first three presuppositions are the same. Therefore, the Christian can legitimately make use of and build upon the findings of secular scientists. The doctrine of common grace states that God’s favor and goodness are showered on all people; He endows everyone with intellect, reason, and talents. People are able to function in God’s world because He is good, even though they may hold Him in contempt or even hate Him.

Yet in our century the evangelical church has tended to deny any validity to psychological findings because of its adverse reaction to various philosophical interpretations by Sigmund Freud, Carl Rogers, B. F. Skinner, and others. The fact is that although their philosophical conclusions are doubtless anti-Christian, their empirical findings are not. Whether or not they acknowledge that human personality is made in the image of God, the fact remains that they have made a thorough study of personality. Recognizing that God reveals Himself not only in the Bible through special revelation, but also through general revelation, we can accept the findings of non-Christian scientists to the extent that their non-Christian presuppositions have not colored the truth discovered.

FIGURE 2 The Christian World-View (based on a figure in Dye, Faith and the Physical World, p. 76)

Francis Schaeffer, a leading philosopher of our day, sounds this note in his insistence that “not all science is junk.” Schaeffer is following the lead of Cornelius Van Til, who in his younger days stressed that non-Christian scientists using Christian presuppositions (“borrowed capital” he called them) bring to light “a great deal of truth about the facts a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- PART ONE: Christianity and Psychology

- PART TWO: The Loss and Restoration of Personal Identity

- PART THREE: The Essentials of Christian Counseling

- APPENDIX: Preface to A Discourse on Trouble of Mind and the Disease of Melancholy (Timothy Rogers)

- Bibliography

- Index

- Back Cover