- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A popular introduction to archaeology and the methods archaeologists use to reconstruct the history of ancient Israel.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Doing Archaeology in the Land of the Bible by John D. Currid in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Ancient Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

What in the World Is Archaeology?

What exactly is archaeology? The term conjures up a variety of images. To some it implies romantic adventure: the search for long-lost civilizations, for the definitive interpretation of the Shroud of Turin, and for the location of Noah’s ark. Others see archaeology as a thing of the past. It evokes images of a khaki-clad Westerner donning a pith helmet and examining dry and dusty remains. To still others it suggests grinning skeletons, missing links, and poisonous snakes (who can forget Indiana Jones’s comment, “Not snakes! I hate snakes!”?). Popular visions of archaeology sometimes border on the bizarre. For example, inasmuch as “no man knows [Moses’] burial place to this day” (Deut. 34:6), I was once asked to equip an expedition to find his bones in the land of Moab. Pyramid power, extraterrestrial spaceships, and King Tut’s curse are viewed as part of the archaeologist’s domain. Children may say that they want to grow up to be archaeologists because of the glamour and adventure involved.

None of those ideas is close to the truth, and they do no justice to the practice of archaeology today. One hundred fifty years ago the notion of archaeology as adventure and glamour may have been more accurate; even serious work back then was no more than mere treasure-hunting. The modus operandi at that time was “to recover as many valuables as possible in the shortest time” (Fagan 1978, 3). But what about today? What is archaeology all about?

The term archaeology derives from two Greek words: archaios, which means “ancient, from the beginning,” and logos, “a word.” Etymologically, therefore, it signifies a word about or study of antiquity. And that is how the term was employed by ancient writers. Plato, for example, notes that the Lacedaemonians “are very fond of hearing about the genealogies of heroes and men, Socrates, and the foundations of cities in ancient times and, in short, about archaeology in general” (Hippias 285d). In the introduction to the History of the Peloponnesian War Thucydides summarizes the earlier history of Greece under the title “Archaeology.” Denis of Halicarnassus wrote a history of Rome called Roman Archaeology. Similarly, Josephus called his history of the Jews Archaeology. The fact is, the word “archaeology” was “synonymous with ancient history” (de Vaux 1970, 65).

The modern sense of the word “archaeology” is much different. Archaeology is the study of the material remains of the past (Chippindale 1996, 42). It is concerned with the physical, the material side of life. “Archaeology, therefore, is limited to the realia, but it studies all the realia, from the greatest classical monuments to the locations of prehistoric fireplaces, from art works to small everyday utensils . . . in short, everything which exhibits a trace of the presence or activity of man. Archaeology seeks, describes, and classifies these materials” (de Vaux 1970, 65). This physical focus is underscored by Stuart Piggott’s dictum that “archaeology is the science of rubbish.”

The aim of archaeology is to discover, rescue, observe, and preserve buried fragments of antiquity and to use them to help reconstruct ancient life. It aids our perception of humankind’s “complex and changing relationship with [the] environment” (Fagan 1978, 18). Archaeology can speak to every aspect of ancient society, whether it be government, cult, animal husbandry, agriculture, or whatever. It is, in short, “the method of finding out about the past of the human race in its material aspects, and the study of the products of this past” (Kenyon 1957, 9).

The discipline of archaeology has a very practical application for us. It tells us where we have come from and how we have developed; it provides very detailed information about our history. Archaeology can also serve as a barometer of the future. As George Santayana observed, whoever does not know history is bound to repeat it.

The written materials of antiquity do not belong to the field of archaeology proper. Written records are more the province of historians than archaeologists. Although the latter often dig up the written works, analysis and study thereof belong to the epigraphers, paleographers, and historians. The “importance of archaeology obviously decreases as written records become more plentiful” (Avi-Yonah 1974, 1).

Archaeology, then, is an auxiliary science of history. It is the handmaid of history, helping its study by revealing necessary information (Wiseman and Yamauchi 1979, 4). In fact, it provides data that written records normally do not. Ancient writing was restricted to an elite class and frequently biased (Chippindale 1996, 43). Archaeology by contrast describes and explains to us how all types of people lived, from the agricultural peasant to the king on his throne. Archaeology is no respecter or discriminator of class. Rather, it broadens our understanding of antiquity in ways that written documents cannot.

Archaeology is often considered to be a social science. It is in fact “the sole discipline in the social sciences concerned with reconstructing and understanding human behavior on the basis of the material remains left by our prehistoric and historic forebears” (Michaels 1996, 42). Accordingly, it is categorized in the United States as one of the four subdisciplines of anthropology, along with cultural anthropology, physical anthropology, and linguistics. Because of its focus, however, archaeology remains singular among the social sciences.

As a social science, archaeology is, of course, not an exact or natural science along the lines of chemistry or physics (Wiseman and Yamauchi 1979, 4). Not as systematic as those fields, it is necessarily more subjective and selective in its analysis and interpretation.

The study of archaeology has four basic divisions:

- Prehistoric archaeology is concerned with the material remains of human activity before written records.

- Preclassical archaeology focuses on the eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It studies the ancient societies that developed in Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Palestine.

- Classical archaeology concentrates on Greco-Roman civilizations.

- Historical archaeology attempts to supplement written texts by describing the day-to-day operation of the cultures that produced them. A large subsection is called industrial archaeology because it focuses upon Western societies since the Industrial Revolution.

Archaeological method itself is subdivided into two parts: exploration and excavation. It is not always necessary to excavate in order to obtain valuable information about antiquity. Much can be gleaned from surface examination. But excavation is, of course, preferable because it provides deeper (!) and broader information.

The Beginnings of Archaeology

Modern archaeological excavation started with organized digs at Herculaneum (1738), located along the Bay of Naples (Albright 1957, 26). Tunnels dug at Herculaneum led to the recovery of magnificent statuary now housed in the Naples Museum. Karl Weber drew some very accurate architectural plans during these early excavations. The digs were eventually suspended at Herculaneum because of the great problem of having to chop through meters of volcanic residue that covered the site.

Excavations at Pompeii soon followed (1748). The first buildings to be excavated included “the smaller theatre (or Odeon, 1764), the Temple of Isis (1764), the so-called Gladiators’ barracks (1767), and the Villa of Diomedes outside the Herculaneum Gate (1771)” (Gersbach 1996, 275).

Systematic archaeological work in the Near East did not begin until the turn to the nineteenth century. In 1798 Napoleon invaded Egypt. He brought with him a scientific expedition of scholars and draftsmen whose purpose was to survey the ancient monuments of Egypt. The account of their discoveries was published in 1809–13 as Description de l’Egypte. This first exploration was important because it opened the eyes of Europe to a vast ancient civilization. What Napoleon said to his troops as they stood beneath the pyramids was really intended for all Europe: “Fifty centuries look down upon you!”

The most significant find of the Napoleonic excursion was the Rosetta Stone (1799). It proved to be invaluable because it was the key to unlocking ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics, a picture script unutilized for over fourteen hundred years. Dating to the time of King Ptolemy V (204–180 B.C.), the Rosetta Stone is inscribed in three scripts: demotic, Greek, and hieroglyphs. The Greek proved to be a translation of the ancient Egyptian language on the stone. The linguistic study of the Rosetta Stone by the English physician Thomas Young (1819) and the Frenchman Jean-François Champollion (1822) “marked the beginning of the scientific reading of hieroglyphs and the first step toward formulation of a system of ancient Egyptian grammar, the basis of modern Egyptology” (Andrews 1996, 620). Thus the first true archaeological find in the Near East was one of the greatest and most critical discoveries in the history of the discipline!

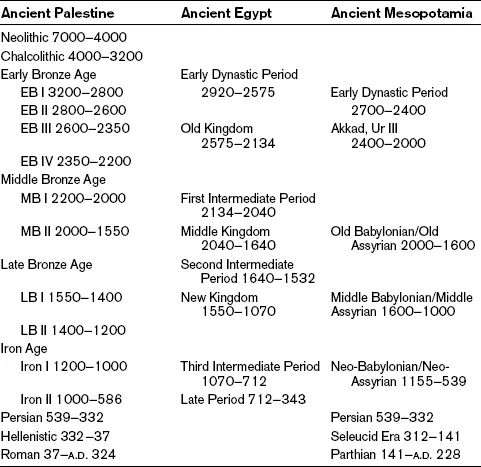

Figure 1

The Ages of Antiquity

Archaeology and the Bible

The archaeology of the Bible is generally understood to fall under the category of preclassical archaeology, and to be a subdivision of Syro-Palestinian archaeology. Whereas the latter covers prehistoric times through the medieval period in Syria-Palestine, biblical archaeology focuses primarily on the Bronze Age, the Iron Age, and the Persian, Hellenistic, and Roman periods in that land. Most events recorded in the Bible occurred within that temporal setting.

The Early Bronze Age (c. 3200–2200 B.C.) was characterized by urbanization, a shift from village life to city dwelling. More settlements appeared in this age than at any time previously, and they were fortified. Full-fledged agricultural production, both fruits and vegetables, also became a major part of life in Palestine. A brisk international trade network was in evidence, especially with Egypt. This was the time of the first great empire building in the ancient Near East with grand states formed in Mesopotamia and Egypt.

The Middle Bronze Age (c. 2200–1550 B.C.) began with a period of decline. Palestine was populated mainly by pastoralists and villagers. Around 2000 B.C., however, a revival occurred, resulting in “the establishment of the Canaanite culture, which flourished during most of the second millennium B.C.E. [Before the Christian Era] and then gradually disintegrated during the last three centuries of that millennium. The second half of MB II [Middle Bronze II] was one of the most prosperous periods in the history of this culture, perhaps even its zenith” (Mazar 1990, 174). Indeed, this period was distinguished by a revolution in almost every aspect of material remains, including architecture, pottery, and patterns of settlement. Many scholars date the patriarchs of the Bible and the beginning of the Hebrew sojourn in Egypt to the latter phase of the Middle Bronze Age.

The Late Bronze Age (c. 1550–1200 B.C.) continued much of the material tradition, though the high culture of the Middle Bronze Age was beginning to erode and evaporate. There was a general decline in urbanization. Most of the settlements, for example, did not even have walls (Gonen 1984, 70). Many researchers fix the Hebrew exodus and conquest of the land of ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Preface

- Abbreviations

- 1. What in the World Is Archaeology?

- 2. A Brief History of Palestinian Archaeology

- 3. The Tales of Tells

- 4. Living by Site (Surveying)

- 5. Why Dig There? The Ins and Outs of Site Identification

- 6. In the Beginning: How to Excavate a Tell

- 7. Petrie, Pottery, and Potsherds

- 8. Buildings

- 9. Small Finds

- 10. Archaeology in Use: The Recovery of Bethsaida

- Notes

- Index